💡 The role of micromobility in mobility

💡 The role of micromobility in mobility

by Joelle Touré, delegate general, Futura-Mobility

On 3 June 2020, a video conference organised by the French think tank Futura-Mobility explored how micromobility fits into the mobility ecosystem.

The two speakers were asked about the relationship between new modes of light transport – be they for carrying goods or people – and traditional modes designed to massify flow. Mohamed Mezghani, secretary general of the International Association of Public Transport (UITP) and Laetitia Dablanc, director of the chair Cité de la Logistique at Gustave Eiffel University shed light on this topic from two angles – the former focusing on people mobility, the latter on the mobility of goods.

The rise of micromobility

Mohamed Mezghani identified two reasons why micromobility (bikes, mopeds, scooters… electric or not, shared and accessible via mobile apps) has taken off in recent years in passenger transport. Firstly, the short distances of most journeys: “In France, for instance, 25% of motorised trips are under 1km, 50% under 3km, and 90% under 10km,” he pointed out. Then secondly, the fact these personal transport devices can connect passengers to their departure and/or arrival points, as well as the mass transport network.

The rapid development of digital technologies and the sharing economy is driving the rest. Using these micromobility devices in cities today has never been so easy

At the same time, the vision of passenger transport has shifted from supply to demand, from transport infrastructure/networks to services; in short, from ready-to-wear to tailor-made.

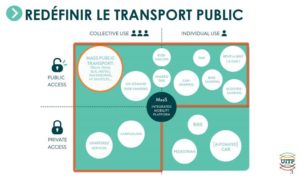

Thus Mr Mezghani confirmed: “For us at UITP, micromobility is an integral part of public transport because it meets objectives that are also converging, namely: better use of urban space, less emissions of pollutants and greenhouse gases; plus micromobility modes can be easily combined with traditional public transport – both physically and in terms of services and fares through the Mobility as a Service [MaaS] approach.”

Furthermore, micromobility extends the reach of public transport “by deploying new options in low-density areas where it would be impossible to financially justify high-capacity public transport networks.”

Take, for instance, the public-private partnerships being forged between mass transport operators and micromobility operators. Like Spain’s national rail operator Renfe, which has established plenty of alliances, in particular with e-scooter operator Circ, which will even be integrated into a MaaS platform in 2020. “More recently, Blablacar has entered into a strategic partnership with e-scooter operator Voi so it can cover customers’ door-to-door trips.”

In the field of logistics, micromobility is homing in on the last mile and even “now, as they say in the business, on the last 15 metres,” added Laetitia Dablanc. Still very traditional, the sector is changing fast, “with a great many developments and innovations that are impacting the whole world; with players who are very similar or the same everywhere!”

Today, deliveries in large cities are essentially done with a human driving a van or a two-wheeler using diesel. “This is the norm for deliveries,” explained Ms Dablanc. Besides electrifying vehicles, a rapidly growing segment, other means of transport are developing, although their market share remains relatively small. “With Covid-19, we have seen an acceleration in trial services,” nevertheless said Laetitia Dablanc.

Henceforth, drone deliveries are ‘taking off’. In the US, Fedex and UPS are now authorised to use them on campuses and at hospitals, i.e. for ‘closed’ environments. In Iceland, Flytrex has established a regular flight path for food deliveries. In China, e-commerce platform giant JD accelerated its roll-out of drones and robots during the Covid-19 crisis, especially in Wuhan.

“In the US, Nuro – a street not a pavement robot – is developing the most for common use,” analysed Laetitia Dablanc. Starship in the U.K., which has been using droids for several years now, has announced it is ramping up development. Yet, warned Ms Dablanc: “Once again, for the time being we are talking about quite marginal market share.”

Deliveries by electric-assist cargo bikes, “which have two to four times less capacity than a van, are becoming a bona fida small market,” especially in Europe. A fast growing market, too. “Its key strength is access to bike lanes,” pointed out Laetitia Dablanc.

Another interesting initiative, “the Fludis service on the Seine, operating between port de Gennevilliers [north of Paris ] and city centre, combines three innovations”: the barge itself is electric, it is loaded on both the outward and return trips, and the travel time is used to recharge the cargo bikes on board. But since “this service is still quite expensive in terms of operating costs”, it is struggling to establish itself in a sector where margins are low.

Rapidly changing business or organisation models

In passenger transport, business models are changing and often fast due to Covid-19.

Micromobility operators, for instance, appear to be “refocusing more on local customers because there are fewer tourists,” pointed out Mohamed Mezghani. This move is stimulating a boom in offers based on subscriptions or long-term rental (Pony, Spin, Wheels – by the way avoiding health issues). Pick-up points for e-scooters are also being tweaked to get closer to this local customer base.

“Some [operators] are also diversifing their revenue streams by using e-scooters for deliveries.” This is the case for Voi, Dott, Gotcha…. Others, like Velib, Voi, Cityscoot, and Tier, are developing “corporate offerings so companies can propose this kind of mobility to their employees.”

Cooperation, like pooling bike storage or cleaning services, between rival operators is also emerging. “As will soon be the case in Lyon,” added Mohamed Mezghani.

Another development is the shift towards a “public service scheme for micromobility: a trend whereby the public authorities want to regain control of these services.” This implies a change of business model for micromobility operators: they could be financially supported by transport organising authorities instead of being charged fees. For the organising authorities, the advantage here is that they can better integrate these services into traditional public transport and better control supply and service quality.

On the goods transport side, “logistics will change a lot between now and 2050 but, more in terms of service and organisational innovations within companies, e-merchants in particular, than technological innovations,” anticipates Laetitia Dablanc.

“Most striking is the rise of outside-the-home deliveries.” These concern convenience stores in Europe, concierge services in Manhattan, or automatic lockers in Asia, the US and Germany. Such is their growing popularity, “new-build, large residential complexes, in China for example, now systematically include large parcel boxes.”

Online consumption and mobility practices: crossing views from Paris and NYC

“A significant innovation because it uses algorithms and applications that everyone has to hand is instant delivery,” i.e. within two hours. The phenomenon started with meal deliveries and has since extended to other types of product. A self-employed activity, it raises questions about labour law worldwide. Yet Laetitia Dablanc points out how “[instant delivery] also represents tens of thousands of unskilled jobs available in major city centres, including for vulnerable populations like immigrants.”

So-called “crowd-sourced deliveries” represent yet another emerging niche market. It involves private individuals with transport capacity in their backpacks or in the boots/backs of their hire vehicles during or in addition to their trip. “In France, the payment must only cover transport costs and under no circumstances should constitute a job, because transporting goods is strictly regulated,” Ms Dablanc explained.

Amazon Flex appears as an intermediate model. “The big brands have more and more urban warehouses so they can do same-day deliveries, or deliver within two hours, or even one hour for Amazon Prime Now, for people living in large cities,” expanded Laetitia Dablanc. In Los Angeles, Amazon owns 15 warehouses in the heart of the city. And here for Amazon, private individuals are doing the deliveries. “This is sizeable in terms of the traffic generated! […]. For a small warehouse with 10,000 to 20,000 square metres of space, you have 45 trucks, 250 vans, and 850 individual Amazon Flex cars coming and going every day!”

Paris, for instance, has taken the step to retain a logistics warehouse in the city, over several storeys “to grab less land,” explained Ms Dablanc. Here, no deliveries by individual cars but an Amazon service provider who uses the rooftop as a parking lot and recharging point for its electric vans. Ville de Paris has also successfully promoted its multi-storey ‘logistics hotels’ designed for mixed use (logistics but also offices or sports facilities). Small urban warehouses are thus appearing – sometimes even on the streets in China! – and becoming “points of final, networked massification for a brand, prior to delivery to end-customers”.

With regards local stores, the Covid-19 pandemic has led to many municipalities setting up web platforms providing information on home deliveries from local stores. “I really believe offering these services is going to become the ‘norm’ for small retailers, too,” said Laetitia Dablanc.

Increased competition over occupying public space

One consequence of the rise in micromobility, for both transporting people and goods, is “that urban chaos is becoming more complex,” observed Ms. Dablanc. Indeed, competition is fierce for the space allocated to vehicles, whether on the roads or pavements, between buses, trams, bikes, scooters, delivery droids (on the pavements) or robots (on the roads), pedestrians of course… and the car! “We really need to focus on this particular issue of sharing public space in our debates,” concluded Mohamed Mezghani.

Illustrations (article): presentations by M. Mezghani and Ms Dablanc

Cover photo: Flickr-CC-Sam Saunders