🌍 Decarbonising mobility in rural areas, by uses

🌍 Decarbonising mobility in rural areas, by uses

Already expressed in France during the yellow vest crisis in 2018/19, then again at the ballot box, the disappearance of services and community centres in rural areas is creating a feeling of unease among local populations.

In terms of mobility, the challenge is threefold: to also take care of the people living in these areas, all too often in the blind spot; enable them to shift away from depending on private cars; and decarbonise mobility.

During a Futura-Mobility session in September 2024, speakers and participants explored alternative mobility systems to the private car in sparsely populated areas.

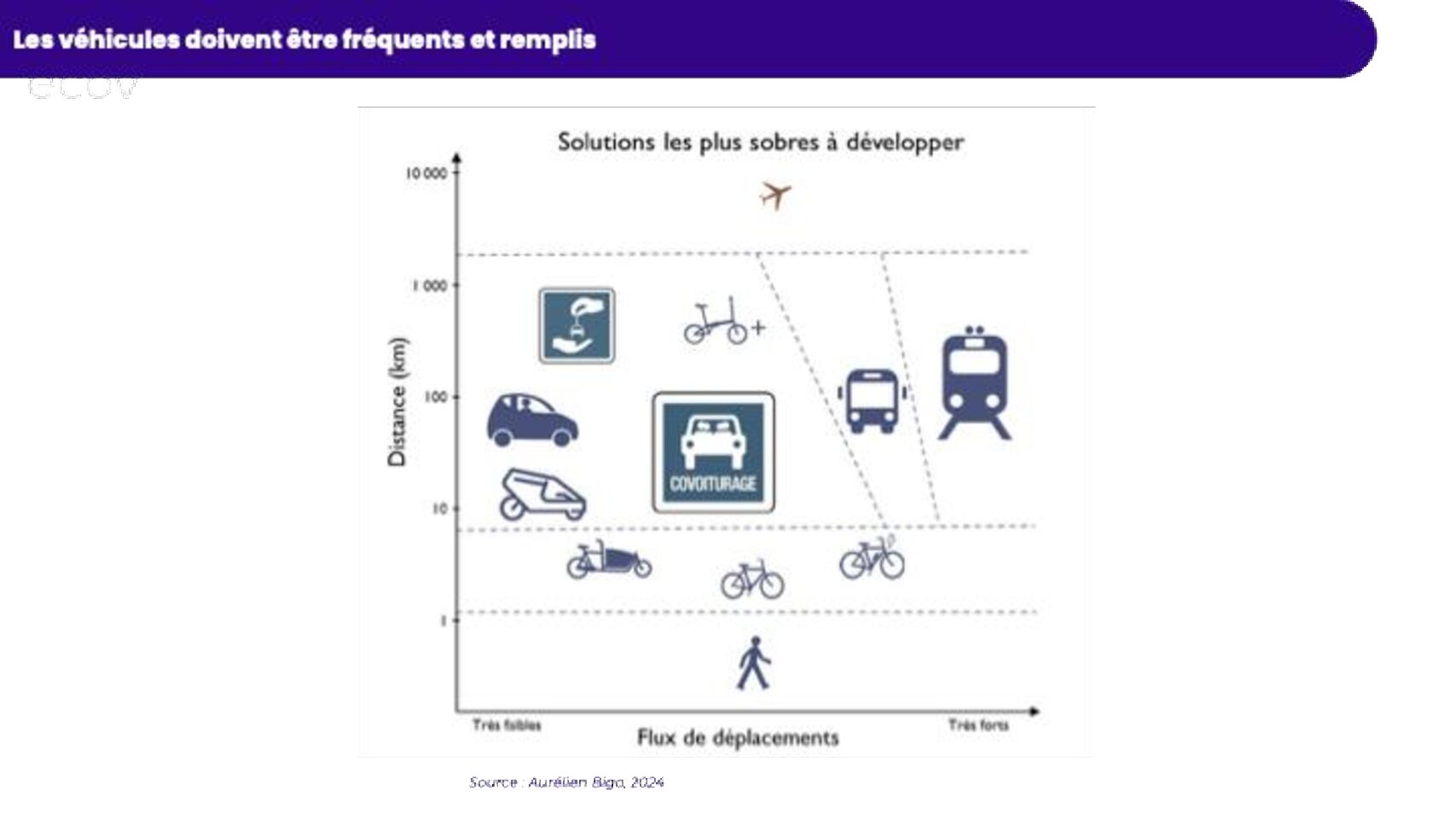

Far from pitting the various solutions against each other, the main takeaway was that they are entirely complementary. The better the offer in rural areas – as is the case in big cities – the more people can do without their car. So it’s a question of creating a positive ‘supply shock’, appropriately calibrated depending on the traffic flow and distances to be travelled, so as to enable people to switch from their own combustion engine cars to less carbon-intensive modes of transport.

In Switzerland – electrification, shared modes and multimodal interfaces

To shift towards sustainable mobility in the future, Switzerland is working on a number of fronts. These include ongoing improvement of public transport services and rail infrastructure, promoting soft modes, especially cycling, shared modes and multimodality, electrification, and so forth.

There are also measures that are less widely adopted in France, such as coordinating transport with land-use planning. Through several planning instruments, such as the Mobility and Territory 2050 transport sector plan, the Agglomeration Traffic Programme, and RAIL 2050 Perspective, interactions and interdependencies between territory and mobility are taken into account to ensure greater consistency between the desired development of activities and urbanisation and the development of transport networks.

Between 2018 and 2023, the proportion of new registrations of pure electric vehicles in Switzerland rose from 1.8% to 20.7%. This is notably down to the drawing up in 2018 of the Roadmap for Electric Mobility, steered by the Confederation and bringing together a number of key economic stakeholders as well as others from the public sector, associations and NGOs, plus the scientific world. However, it is important to bear in mind that “decarbonising transport in Switzerland by 2050, as is the case elsewhere, will require a combination of measures,” says Sara El Kabiri, an expert in mobility policies at the Federal Office for Spatial Development (ARE).

Based on its surface area, Switzerland is a small, predominantly rural country. What makes it different from France is that rural areas account for a relatively small proportion of the population and jobs, which are heavily concentrated in the conurbations.

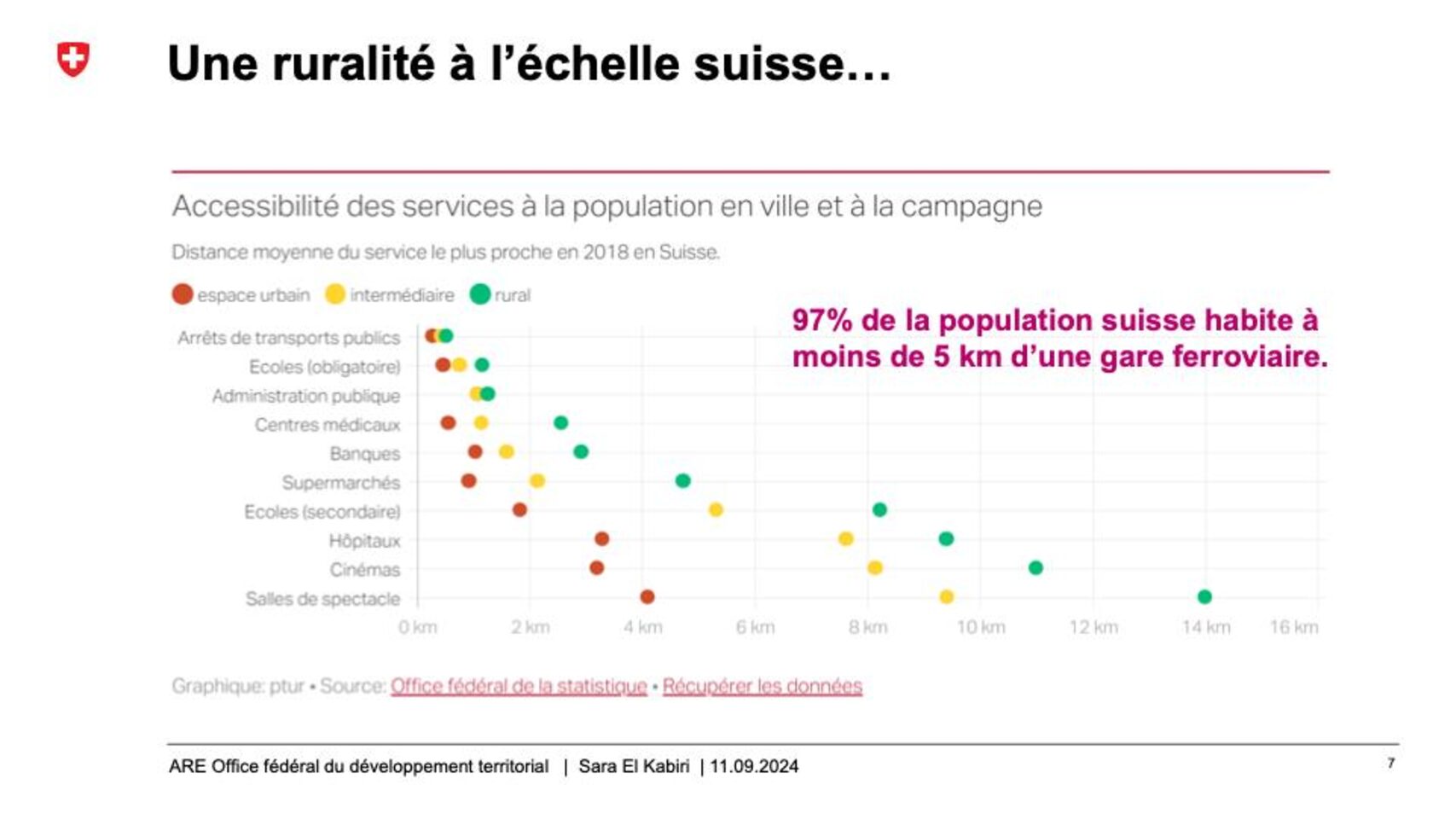

The country has however made great efforts to ensure the entire population is well connected, with a fairly high level of services (see slide above), including high-speed internet. For instance, “97% of the Switzerland’s population live less than 5km from a railway station, and there is little difference between town and country in terms of distance to the nearest public transport stop,” points out Ms El Kabiri.

Yet despite this good transport connectivity nationwide, the private car remains indispensable, especially in certain rural areas. “The quality of public transport coverage varies widely across the country,” explains Ms El Kabiri. ‘The range of services is less extensive, they are less frequent, and the operating hours are not the same either, which reduces the proportion of people using public transport.” For rail, however, ‘the extremely wide coverage of the country, regular timetables, and deeply rooted railway culture in Switzerland are significant advantages.”

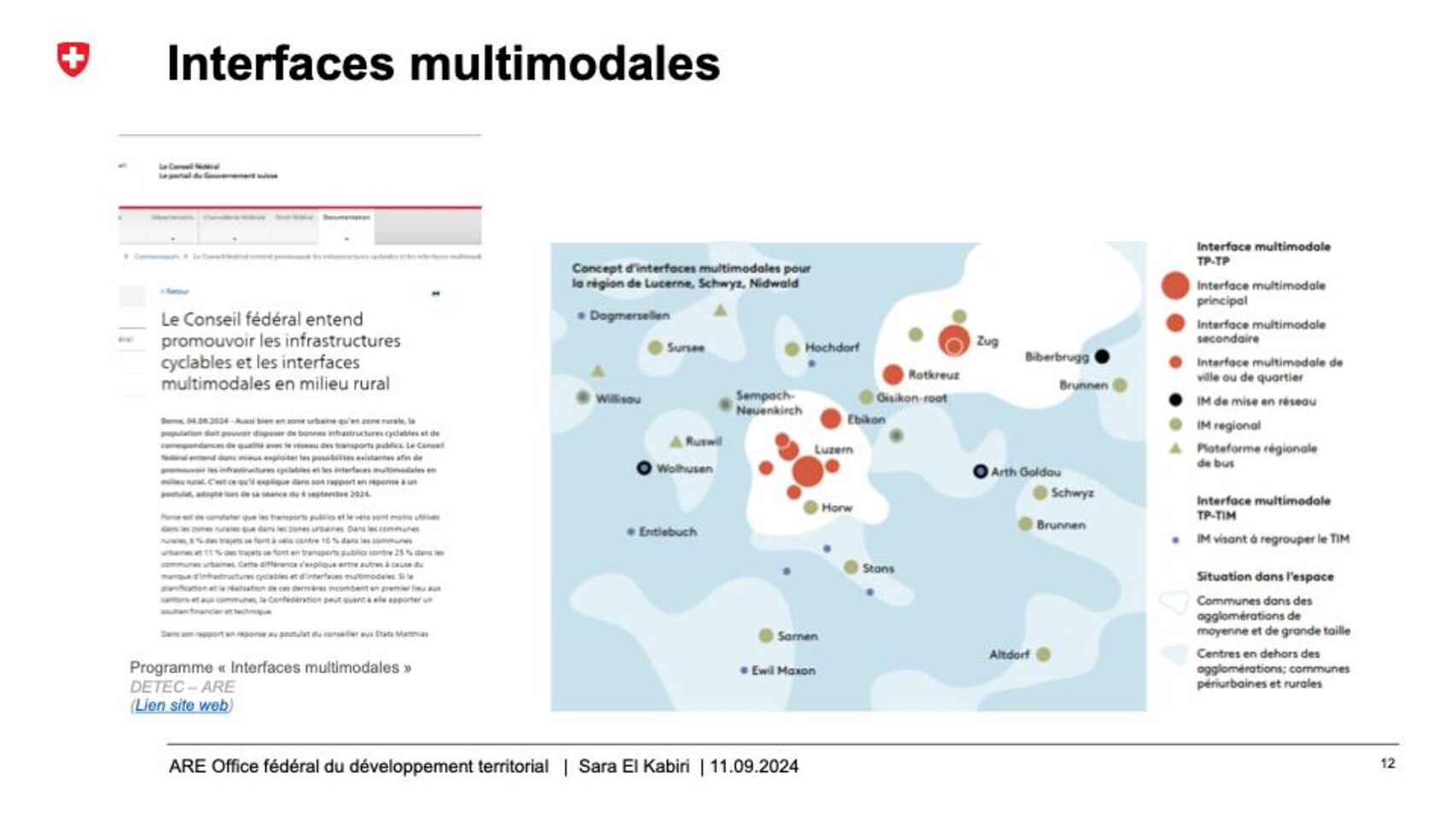

In this context, Switzerland is considering how to decarbonise its transport. “We can certainly rely on the quality of the rail network, but we also need to develop high-quality multimodal interfaces in the right places, and promote other modes of transport, like cycling,” insists Ms El Kabiri.

In line with RAIL 2050 Perspective, the general drive is to develop services for medium and short distances and maintain the quality of existing services.

Why? “On the one hand, to be consistent with land-use planning – densifying inland, where there are already buildings or a concentration of facilities, people, and jobs; on the other, looking to where we could have the greatest potential for modal transfer,” explains Ms El Kabiri. With these pointers in mind, in rural areas the focus will be on electrifying individual motorised modes of transport, but not exclusively. “We will be working on shared modes such as carpooling as well as focusing on multimodal interfaces [hubs serving as transport links between rural and urban areas].”

With these interfaces, the idea is to reach out to people living in outerlying or less densely populated areas and bring them to regional public transport hubs via other means of transport. For rural areas, they will be centrered around regional train stations, with park & ride, bike & ride, bike stations, carpooling, and new kinds of mobility.

In 2021, an agreement was signed by the Confederation, cantons and municipalities, in other words at all three territorial levels, to develop these multimodal interfaces.

Back in France with bikes and intermediate vehicles

Cycling is not just for cities. It’s also for conurbations and rural areas. In France, however, “in conurbations, safety is the main barrier to cycling,” points out Etienne Demur, co-president and spokesman for the French Bicycle Users’ Federation (Fédération française des Usagers de la Bicyclette, FUB). “So if we want to develop bike use outside of towns and cities, we need to work on this.”

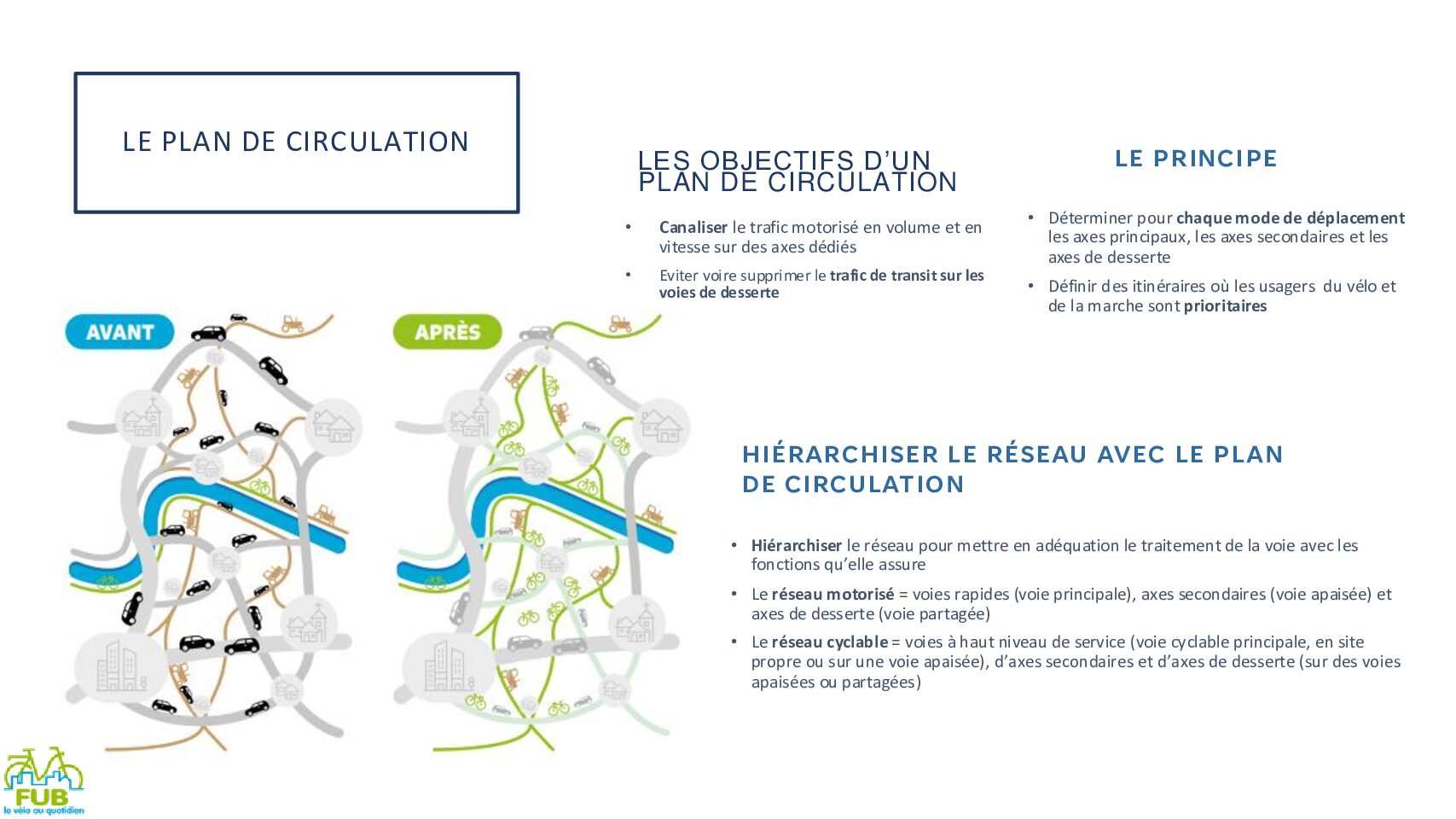

The pragmatic approach adopted by the FUB is based on levers that can be activated rapidly and using existing facilities (lanes, roads, tracks). above all, the Association is proposing to work on the traffic plan, a method, as Mr Demur points out, “proven in different countries and in different contexts.” It will entail channelling car traffic on certain roads in the French network and calming it on others, so that car and bike traffic can be distributed on separate roads. “With this traffic plan, we want to open up part of the road network to more vulnerable mobility by eliminating or significantly reducing the danger posed by cars,” explains Mr Demur. “It’s not about banning cars.”

With this traffic plan, the FUB hopes to get as close as possible to something that can be achieved on the ground, using existing roads, and “to get away from the cliché that if you want to cycle, you need a bike lane alongside main roads.”

By making the bike network in rural areas safer in this way, the FUB should see rapid results, since, as M. Demur points out, many people know how to ride a bike and/or already own one. “You can keep your car but change the way you use it. You can bike on these safe paths for journeys of less than 5km, for example, instead of taking your car.”

In addition to these benefits, making cycling safer in small towns and rural areas will enhance the value of the region for local inhabitants, as well as attracting tourists.

“In rural parts of France, the biggest challenges involve medium and long distances covered on a daily basis, when there are no public transport alternatives,” explains Antoine Dupont, managing director of La Fabrique des Mobilités, an association supported by Ademe (the French Environment and Energy Management Agency) that aims to accelerate testing of innovative solutions in order to decarbonise mobility.

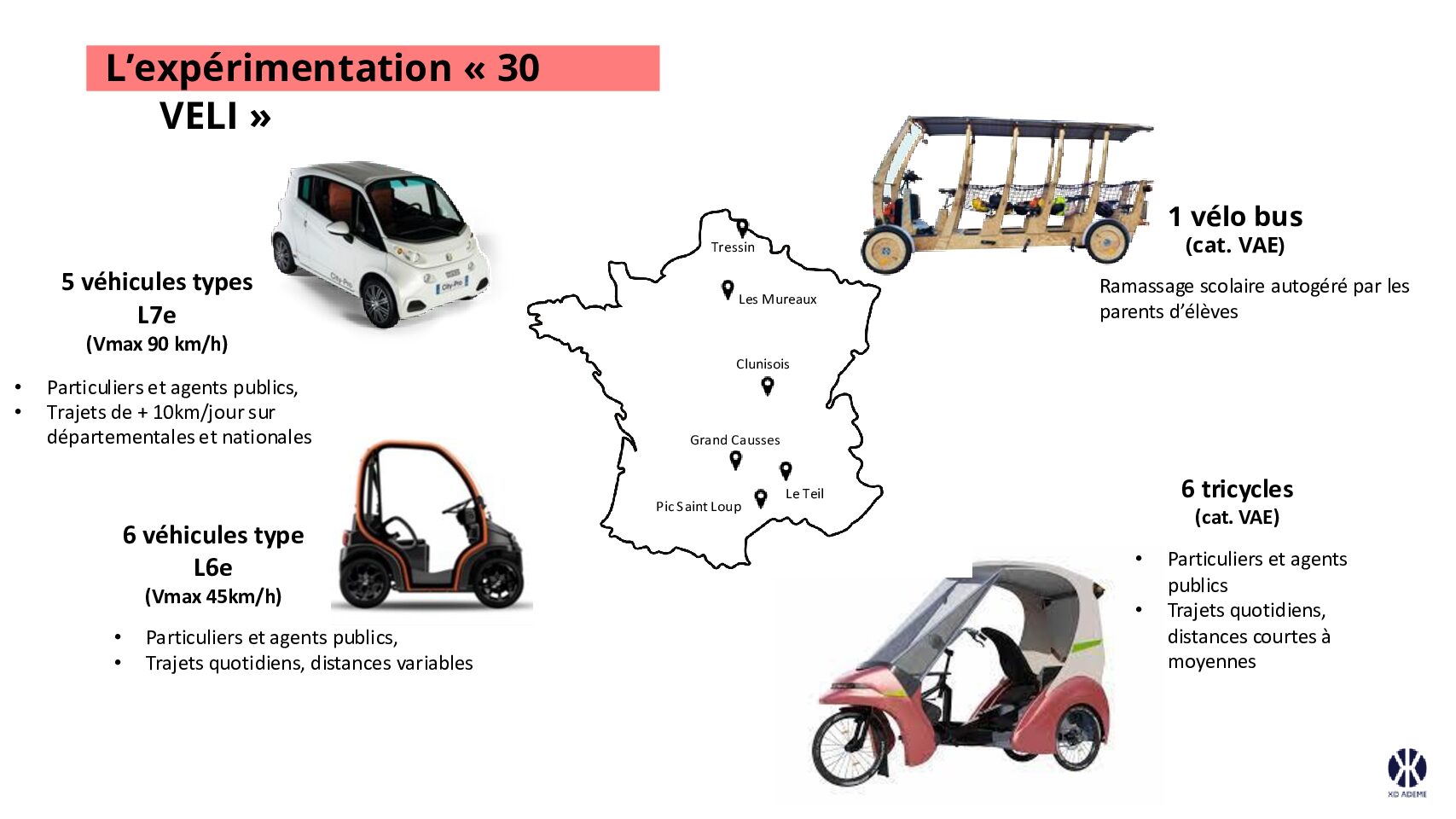

In view of this, Ademe’s Extrême Défi, an initiative launched in 2022, is designed to accelerate the emergence of intermediate vehicles (VELI) by carrying out trials in rural and peri-urban areas. These include pedal-powered quadricycles and augmented bicycles (active VELI), as well as augmented scooters assimilated to cars (passive VELI). “These intermediate vehicles are extremely light and easy to repair, and cost much less to run than a conventional car,” adds Mr Dupont.

As part of the Extrême Défi programme, Fabrique des Mobilités is currently conducting trials of intermediate vehicles with rural and peri-urban local authorities.

Among the use cases being tested are municipal workers using passive VELI vehicles instead of conventional cars to travel between towns. Or school transport organised by parents, pupils, and a local authority employee using a bike bus, “which also has an educational purpose behind it,” adds Mr Dupont.

At the same time, Ademe is also helping VELI stakeholders, small and medium-sized businesses, meet with local authorities, find sites for testing grounds, and obtain financial support.

“For some of them, finding funding to industrialise their equipment is a problem,” points out Mr Dupont. ‘Some passive VELI vehicles, even small ones, require several million euros to go through to industrial production, along with the certification that accompanies it.”

To speed up development of this offer and industrialisation of VELIs, the France 2030 investment plan is providing €15 million in funding for Extrême Défi.

“The market for intermediate vehicles is exploding in China and will soon be arriving in Europe,” concludes Mr Dupont.

The car, differently

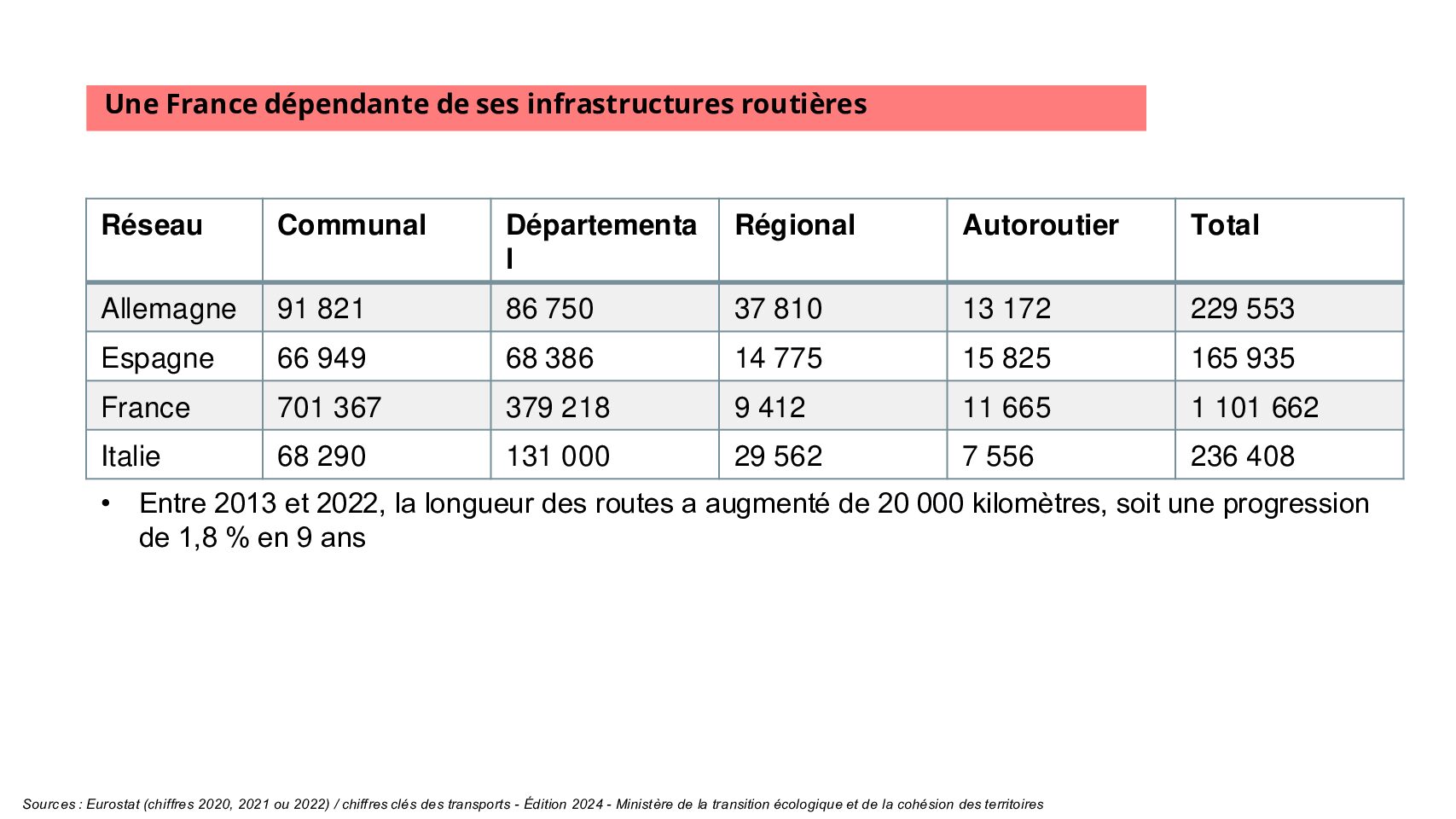

The French are particularly dependent on the road and the car. Cars are used for 81% of the kilometres travelled in France[1]. Eighty six percent of the French use their car for at least one everyday trip[2] and of these, 51% would like to do without it but feel they can’t. This proportion rises to 60% in suburban areas and 67% in rural[3]. Moreover, road infrastructure in France is four times more extensive than elsewhere in Europe (see slide below).

Where there is no alternative, why don’t motorists share their vehicles? According to a study by Vinci Autoroutes, over 80% of motorists in France prefer to drive alone rather than share their vehicle. This isn’t because they’re used to it, or because they’re comfortable, or because they want social recognition, or simply because the French love their cars, but rather because they associate sharing with constraint.

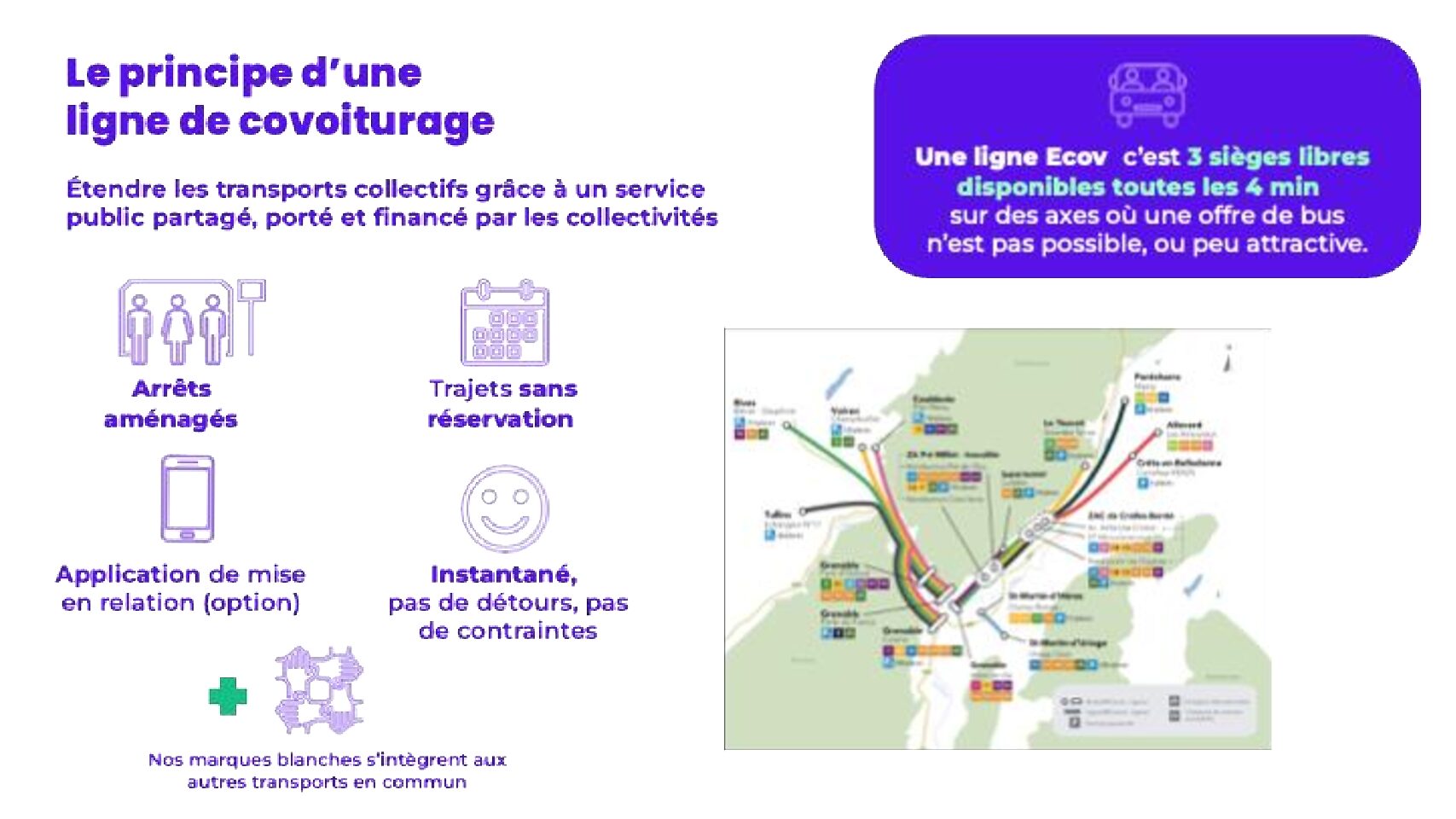

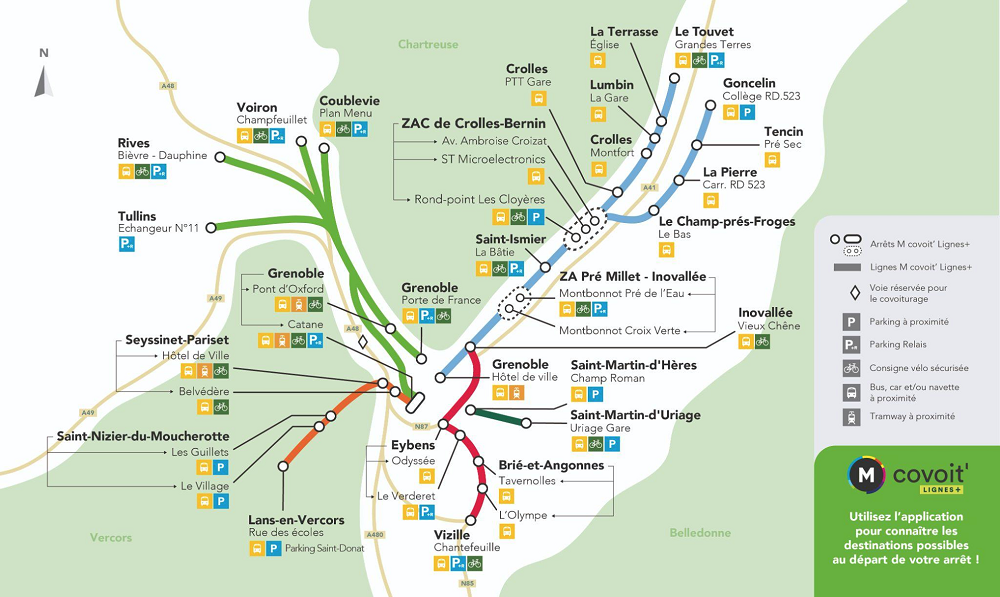

In order to radically reduce the mental load associated with sharing journeys, network the regions, and contribute to decarbonising transport, Ecov is proposing a new public service: carpooling lines. The general idea is to carpool in the same way as taking the bus, transforming the car into a form of public transport.

In terms of user journeys, a rapid carpooling service is similar to any other public transport service, except that available seats are offered by cars on the road.

Drivers follow their usual route. They pass naturally by the stops, can signal their passage via an app and pick up passengers waiting at the stops. For passengers, the experience is similar to quality public transport: no reservation needed, frequent, and reliable. They go to the nearest stop, make their carpooling request on the app and wait for the first driver to stop. They then get in and validate as if they were on a bus.

The stops are designed to adapt to a shift away from single car use and towards intermodal trips, via links with other public transport and with active mobility infrastructure at the carpooling stops, designed as mobility hubs.

Carpooling lines offer frequent services: in 2023, 97% of trips on lines operated by Ecov recorded a waiting time of less than 10 minutes. On certain high service level lines, users can be sure of departing thanks to the introduction of a departure guarantee, used in 1% of cases in 2023.

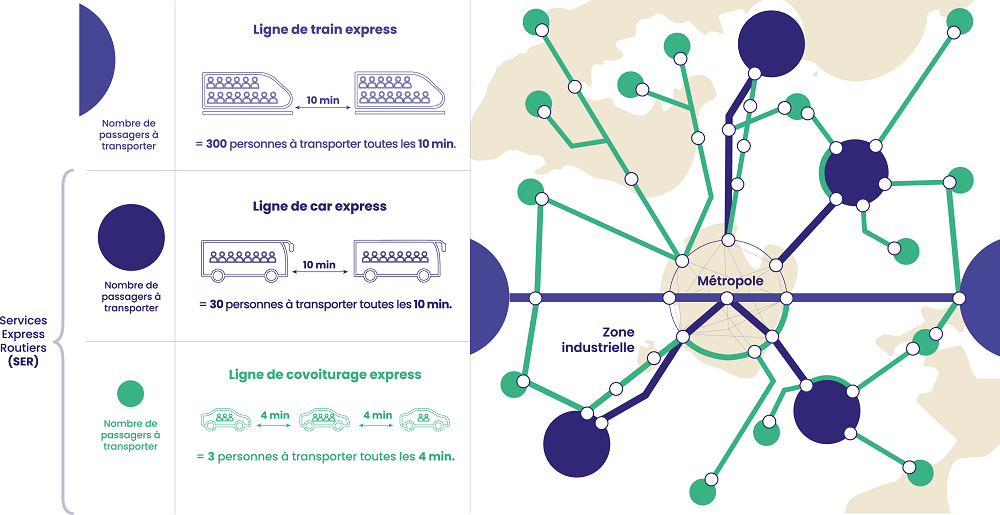

Carpooling lines have recently been integrated into the Services Express Régionaux Métropolitains (SERM), as part of the Services Express Routiers (S.E.R)[5], which comprise rapid coach and rapid carpooling lines. S.E.R. is the road component of SERM, to be rolled out over the short term, but which will also be deployed outside the perimeter of rail nodes.

Thomas Matagne, president and founder of Ecov, presented the potential of a rapid transport network for all, including RER (commuter rail) lines, rapid coach and carpooling lines. A multimodal system like this could closely knit the region, offering a fast, frequent, and reliable transport solution less than 10 minutes from the homes of 80% of the population.

On this subject, Ecov recently published a white paper (in French) entitled Un transport express pour tous dans la France qui conduit, which benefited from contributions by Cerema, Laboratoire Ville Mobilité Transports, the WWF, and Institut Mobilités en Transition.

Another solution that could also play a role in decarbonising transport, this time technological and behavioural, is electrification of cars and car-sharing.

“There are many parts of France where transport demand is extremely low and where the car and self-driving are king,” points out Olivier Rossinelli, managing director of Agilauto Partage. “So we wanted to provide a solution that would first of all address the real issue of social leasing – 84% of French people today cannot afford to buy electric vehicles.”

The trend in car manufacturing towards more high-end vehicles is a second good reason for launching Agilauto Partage. Thanks to its app, users can reserve a shared vehicle in just a few clicks and collect it from parking points. Car-sharing in rural areas is an alternative to owning a second vehicle. ‘We’re focusing on rural areas, because that’s where the real need is,” insists Mr Rossinelli.

Rail

Trains have a relatively good track record when it comes to carbon emissions, yet they still could play a greater part in the collective effort to decarbonise rural mobility.

‘Within SNCF [French Railways], innovative projects and activities are underway with a view to reclaiming the countryside’, explains Olivier Melquiot, director of the Trains très légers programme at SNCF’s Tech4Mobility department. They concern very light vehicles weighing no more than 20 tonnes, travelling at 70 or 100km/hr and taking passenger flow back to existing stations. This approach seeks to encourage a modal shift and thus contribute to decarbonising mobility in rural areas. “SNCF’s historical DNA is speed and lots of passengers,” observes Mr Melquiot. “With these lightweight projects, it’s the complete opposite.”

The most ‘rail-based’ project, Draisy, is designed to revitalise small lines by linking up with regional express trains using a light rail vehicle. With space for 30 passengers seated and 80 standing, this fully electric vehicle, with rapid recharging at the platform, can travel at a maximum speed of 100km/hr.

A little less ‘rail-based’, Flexy is a road/rail vehicle developed with Milla and Michelin to serve small lines. “This shuttle, which travels at 70km/hr, can pick people up from their homes, bus stops, town halls, colleges, and then, like Draisy, provide feeder services to stations,” explains Mr Melquiot.

A third category of light projects at SNCF is exploring abandoned railway rights-of-way: in Carquefou (Pays de la Loire region) for instance, one such right-of-way is being converted into a track dedicated to autonomous vehicles.

“These light projects work in consortium mode, with SNCF taking the leadership and co-funding from government and the consortium,” sums up Mr Melquiot. “For each one, the teams work for a maximum of three to four years to reach the testing site point.”

Public transport and transport on demand – complementary

As a public transport operator, Keolis is tackling the issue of decarbonising territories by examining how to provide the best offer in the territories, while taking into account the constraints, first and foremost the cost to the community. ‘Keolis plays an advisory role and also explores how to rethink the existing offer by analysing services, behaviour patterns, needs, and possible synergies,” explains Arnaud Julien, director of Innovation, Data & Digital at Keolis.

Keolis is focusing in particular on fares and marketing. “Marketing is a real lever for raising awareness of the public transport offer,” confirms Arnaud Julien. In cases where local authorities are facing severe budget constraints, Keolis proposes an innovative financial approach: within a given budget envelope (€100,000, €200,000, etc.), build a multimodal offer that capitalises on existing services by combining them with new ones to maximise the relevance and use of all types of shared mobility: car-sharing, bus routes, stops, demand responsive transport (DRT), etc.

Keolis operates a large number of DRT services, such as Flex’Hop, the public transport service provided by the Compagnie des transports strasbourgeois (CTS). Operated by Keolis since 2021, this is a 100% electric DRT network. It completes the mobility offer in 25 communes of Strasbourg Eurometropole. In operation every day from 5am to midnight, Flex’Hop currently clocks up 20,000 trips a month.

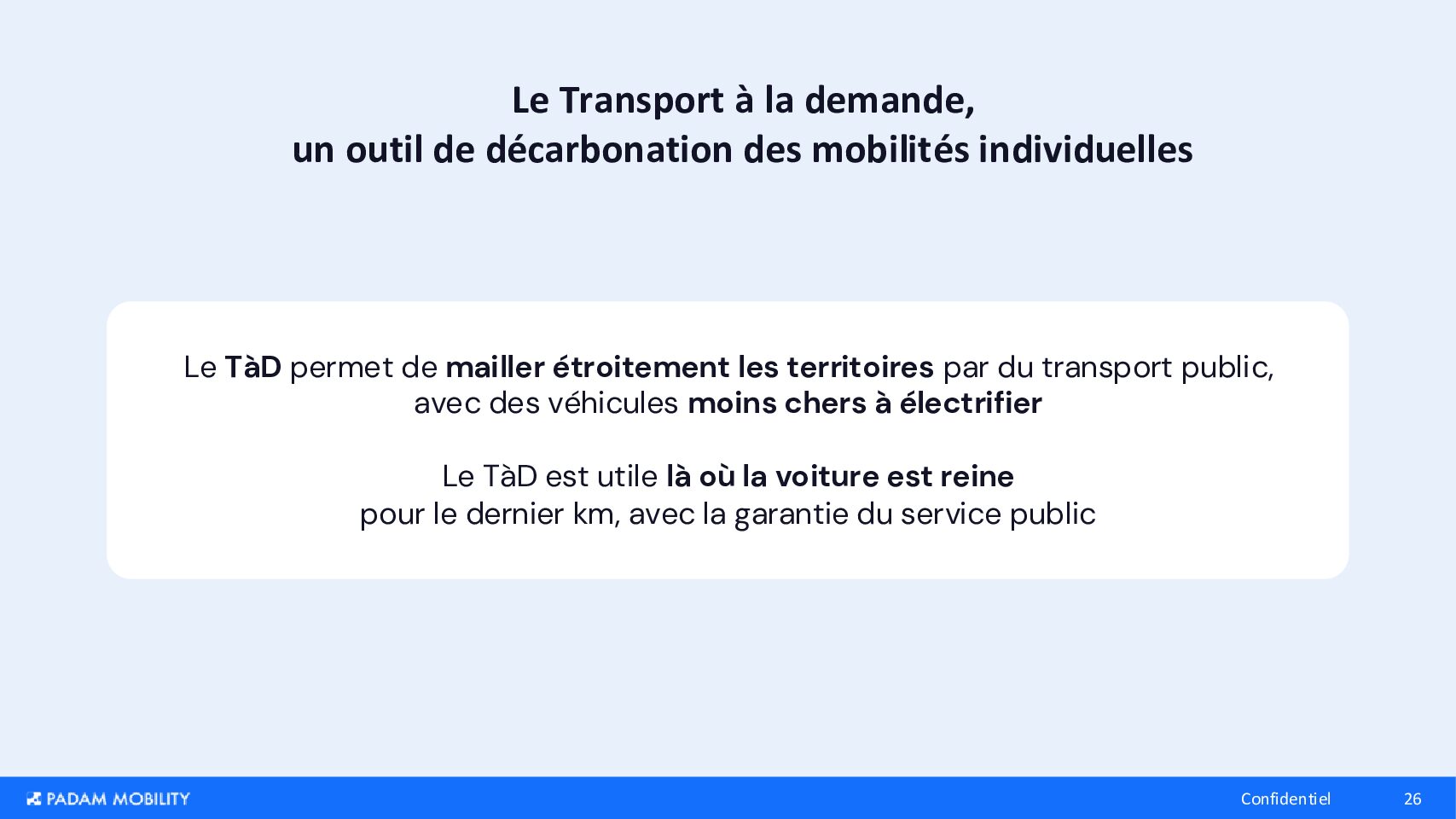

“Demand responsive transport – which today is something like a service between an Uber and a bus – is nothing new, it’s been around for at least 50 years,” points out Claire Duthu, COO of Padam Mobility, a start-up that designs and develops DRT solutions using algorithms, and which worked with Keolis on Flex’Hop.

“What we’re seeing today is democratisation of DRT thanks to technological advances such as digital innovation and mobile phones, which mean we can optimise services and make them more refined, responsive, and attractive.”

“Demand responsive transport is one of the solutions for decarbonising transport because it reduces dependency on private cars, as well as making public transport more efficient,” says Ms Duthu. “In addition, generalising the use of small vehicles is another positive.”

Padam is currently present in Canada and Morocco, as well as a dozen countries in Europe and 160 territories in France.

In the air

Ascendance, a specialist in hybrid electric technologies for decarbonising aviation, has its sights firmly set on regional aircraft as a first step. “We are working to decarbonise air transport and open up regions, especially rural areas,” confirms sales & marketing lead Vincent Joséphine.

“There are several technologies for decarbonising transport,” he explains. “In aviation, we’re talking about all-electricity and hydrogen. However, we’re convinced hybridisation, i.e. combining an internal combustion engine and electric battery pack, is the most tangible and relevant solution for decarbonising since it creates the best balance between performance, aircraft range, and reduced CO2 emissions.”

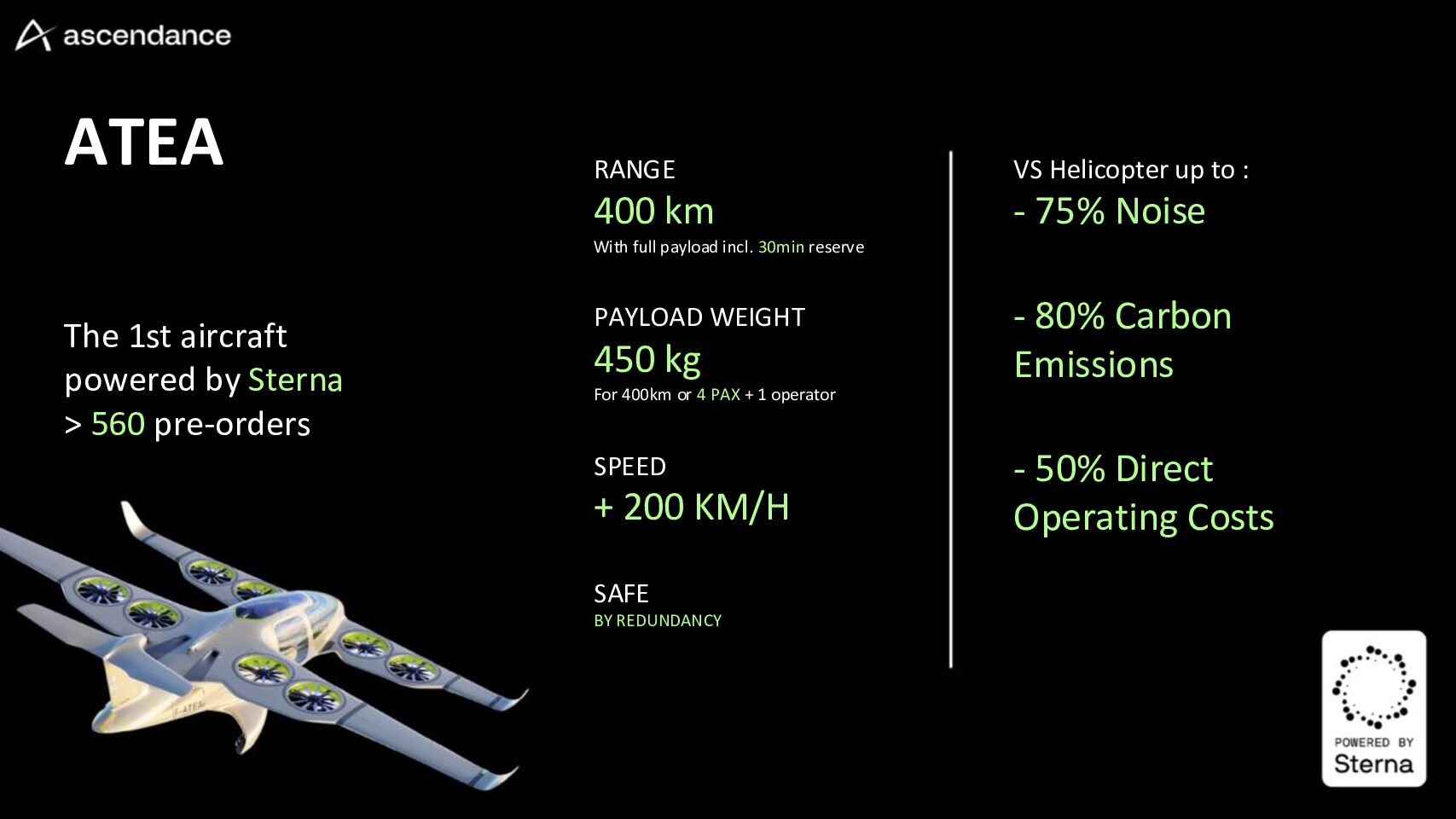

To achieve this, Ascendance is proposing two solutions: retrofitting existing regional aircraft with hybrid-electric technology using STERNA, a hybrid-electric propulsion system; and ATEA, a VTOL (Vertical Take Off & Landing) aircraft ‘Powered by Sterna’, i.e. hybrid-electric.

Currently in the certification phase, ATEA takes off and lands in vertical mode like a helicopter with rotors integrated into the wings. It then switches to cruise mode like an aircraft, using horizontal thrusters and wings to provide lift. Designed to connect areas poorly served by traditional means of transport, ATEA has a range of 400km and can carry up to four people in addition to the pilot. With a payload of 450kg and nearly 600 aircraft already pre-ordered by its customers, ATEA will also serve other purposes, such as emergency medical transport and logistics.

The aircraft is scheduled to enter service in 2028. “We won’t be replacing all the helicopters in the air today, of course, or the car,” concludes Mr Joséphine. “Above all, our multimodal approach ensures our use cases complement each other and meet real needs in terms of regional mobility.”

Ascendance is one of the start-ups cited by Bpifrance Le Hub and France Industrie in their Mapping 2024 of French Start-ups driving Decarbonisation and Reindustrialisation (in French).

Removing obstacles to offer more solutions

All modes of transport have a role to play in the transition to low-carbon rural mobility: public transport, whether timetabled or demand responsive, car-sharing, electric cars, car-pooling, cycling, and even aviation.

However, many challenges still remain. Like the current lack of electric charging points in rural areas.

Carbon impact or social impact? Should we choose? Ms Duthu from Padam Mobility points out that a demand-responsive transport service will generate trips that didn’t necessarily exist before. But she reassures us that “with the right public transport service, it’s compatible.”

There is also a growing awareness that electrification is not the only solution to this decarbonisation challenge.

The biggest obstacle is most certainly the state of public finances and the willingness – or ability? – of transport organising authorities to offer a range of transport solutions that will deliver a real impact of alternative offers in rural areas. While some regions are starting to do this, they unfortunately still remain the exception.