🇦🇹 🐝 How is the transport sector protecting biodiversity in Austria?

🇦🇹 🐝 How is the transport sector protecting biodiversity in Austria?

During Futura-Mobility’s field trip to Austria, in November 2025, the delegation explored the topics of technology, passenger rail governance, and urban and mobility planning. The group also focused close attention on how the country – government, infrastructure managers, and other specialist bodies – are working to reconcile the human need for mobility with growing awareness of the vital importance of sustaining and nurturing biodiversity.

Lying at the heart of the European Union and bordering eight countries, Austria is a transit country with a dense network of roads and rail. Covering an area of around 83,000 square kilometres, it also boasts a rich diversity of fauna and flora, as well as natural habitats ranging from Alpine meadows, mountain forests, and wet grasslands, streams and lakes. This explains why Austrians are so close to nature but also means building infrastructure is more destructive. A pioneer in environmental protection, the country adopted a biodiversity strategy 10 years ago.

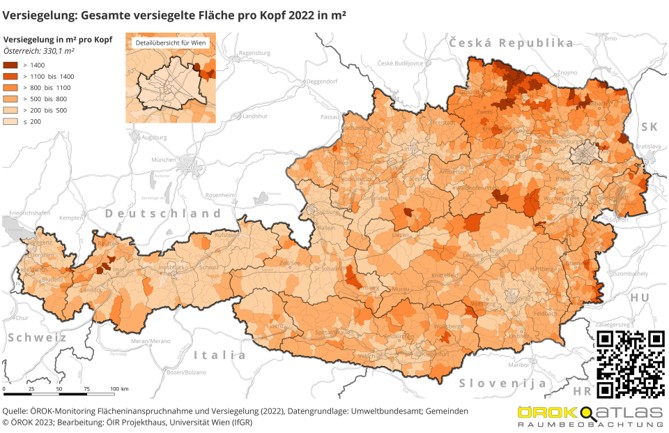

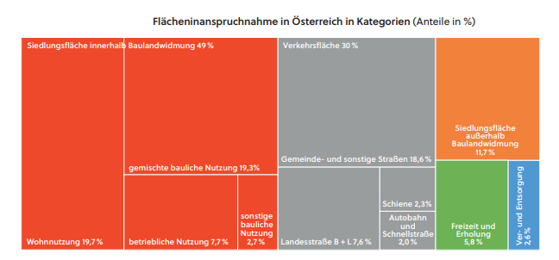

Austria is being built up and sealed (rendered permeable to water and air) too much and too fast. In 2022 alone, it lost more than 5,000 hectares of fields, meadows, pastures, and vineyards. Interestingly, this land take is faster than population growth.

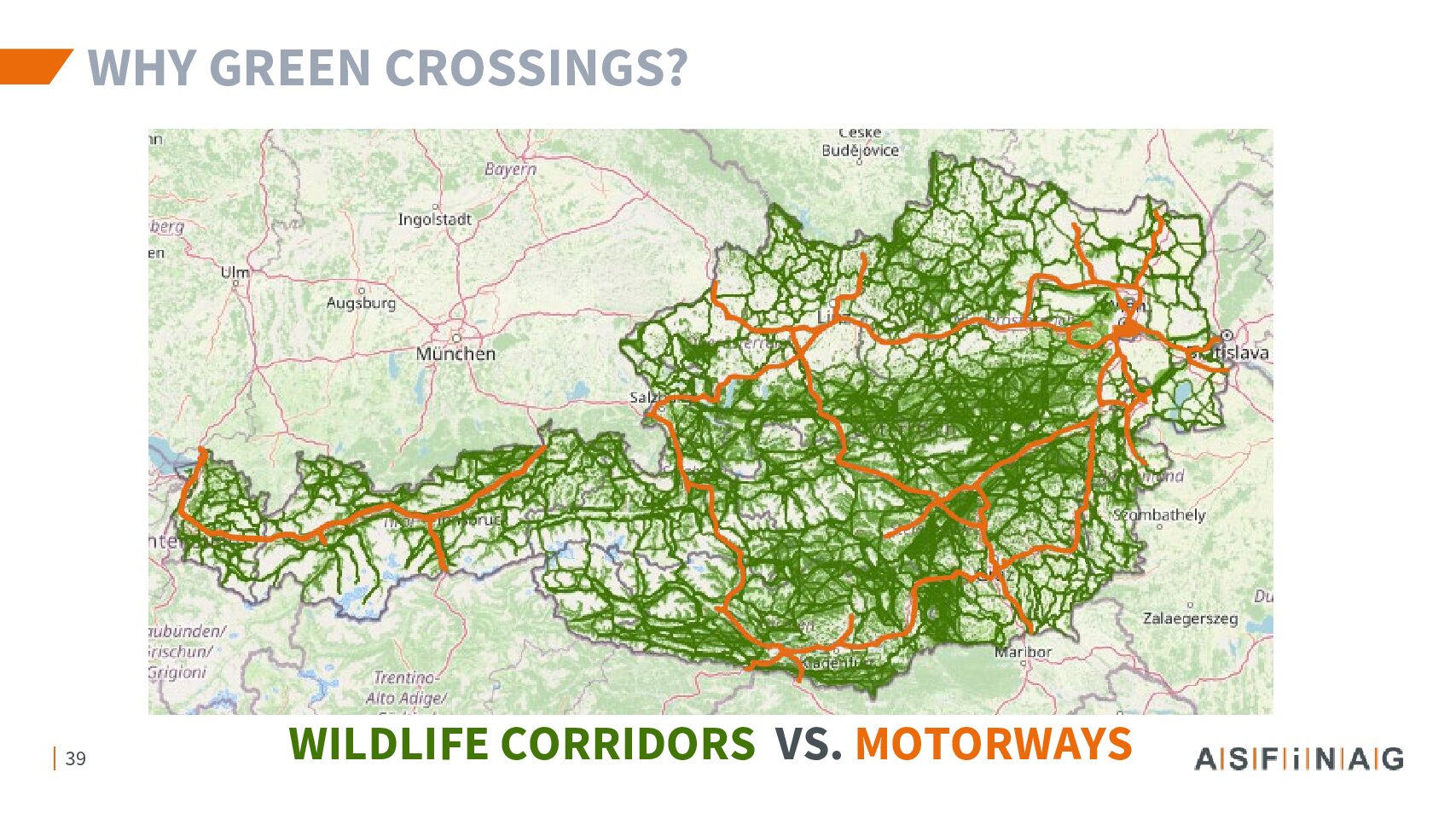

Land fragmentation, especially since the 1950s car boom, has and is being caused mainly by road infrastructure, as well as other developments like housing and utilities. The barriers created by rail tracks and roads, their bridges, tunnels, and fencing block species movement and divide habitats, leading to biodiversity loss and genetic isolation. Roadkill and collisions remain major causes of biodiversity decline.

In this context, ecological connectivity is vital for enabling wildlife on land or in water to move freely from place (or habitat) to place (habitat) to find food, breed, and establish new home territories. It can take the form of corridors and stepping stones such as hedgerows, riverbanks, and small forests, all of which facilitate movement between habitats. Or mitigation measures like wildlife crossings, tunnels, and habitat restoration, which serve to reconnect landscapes fragmented by human-built infrastructure.

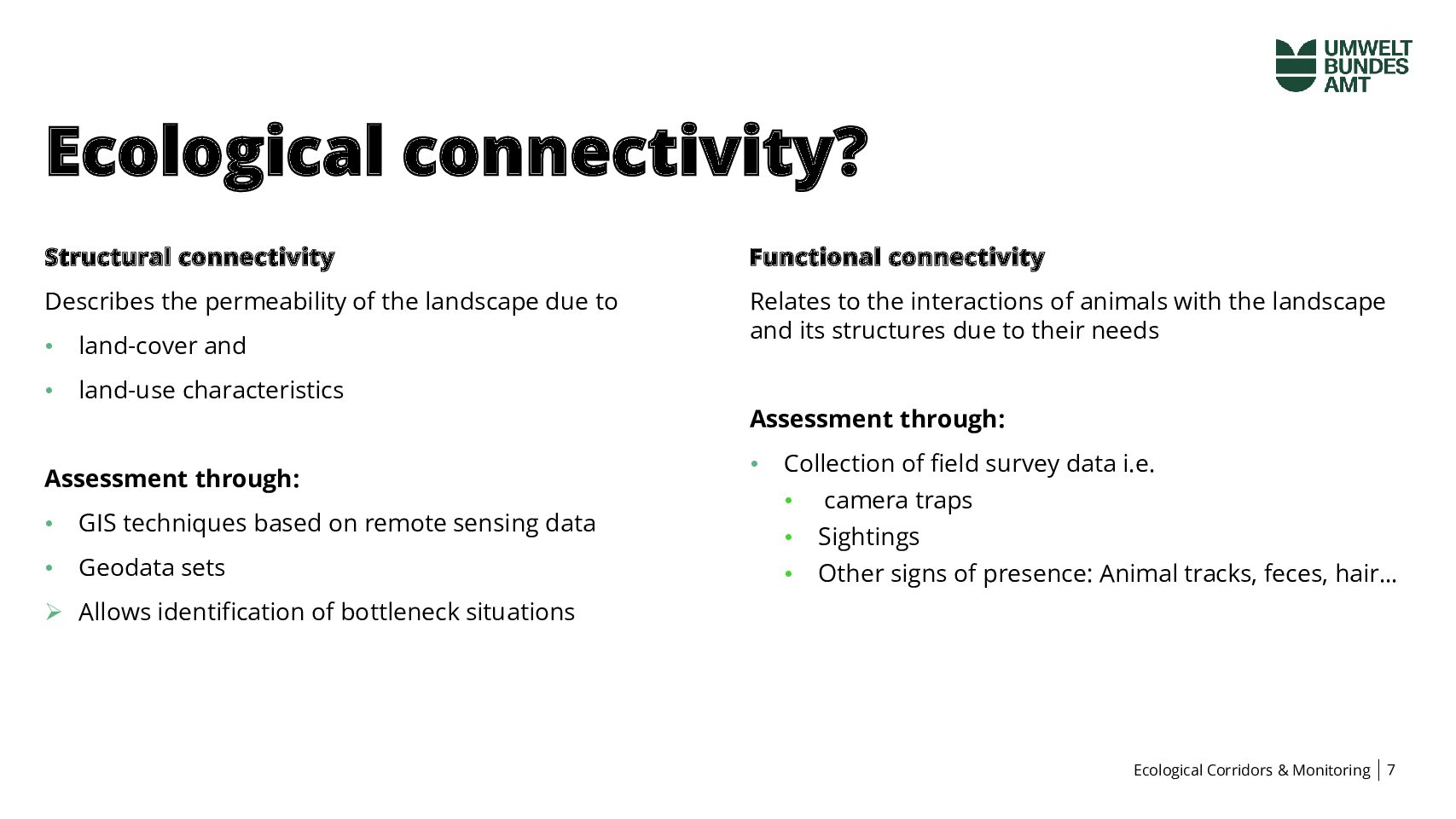

Environment Agency Austria (Umweltbundesamt) – a specialist in monitoring, managing, and evaluating environmental data, and developing scenarios to reach environmental policy objectives both in Austria and in Europe – centres its work on ecological connectivity around the concepts of structure and function.

Structural connectivity describes the permeability of a landscape for wildlife based on land-cover and land-use. “We assess this using GIS techniques based on remote sensing data and the use of geodata,” says Theresa Walter, remote sensing & spatial analyst, Environment Agency Austria. Functional connectivity describes how animals interact with the landscape and its structures based on their needs (food, reproduction, etc). “This is assessed by collecting field survey data (camera traps), sightings, and other signs of presence such as animal tracks, faeces, or hair.”

Aware of the need for a nationwide analysis of the corridors, in 2023, the Agency carried out a GIS analysis of structure (fields and forests) and also landscape elements (single tree, single hedgerow. “By combining the two it was possible to understand how wildlife is able or unable to move through the landscape,” explains Ms Walter.

The Agency evaluated functional connectivity as part of SaveGREEN, a European Union project (2020-2022) for safeguarding ecological corridors based on integrated planning. This work involved using camera traps on green bridges in Austria, as well as on road bridges and underpasses at two pilot areas. A total of nearly 60,000 activities were recorded showing both animal and human activity patterns.

Encouraging infrastructure managers to work together

At regulatory level, the Austrian government is stepping up efforts to safeguard biodiversity through conservation policies, planning guidelines, legal and ecological frameworks, mapping and policies for transport and land-use planning.

“While not part of early transport planning in Austria, recent awareness of ecological connectivity has led to mapping and policy integration of green infrastructure,” explains Julia Sattlberger from the Federal Ministry of Innovation, Mobility and Infrastructure (Bundesministerium für Innovation, Mobilität und Infrastruktur, BMIMI).

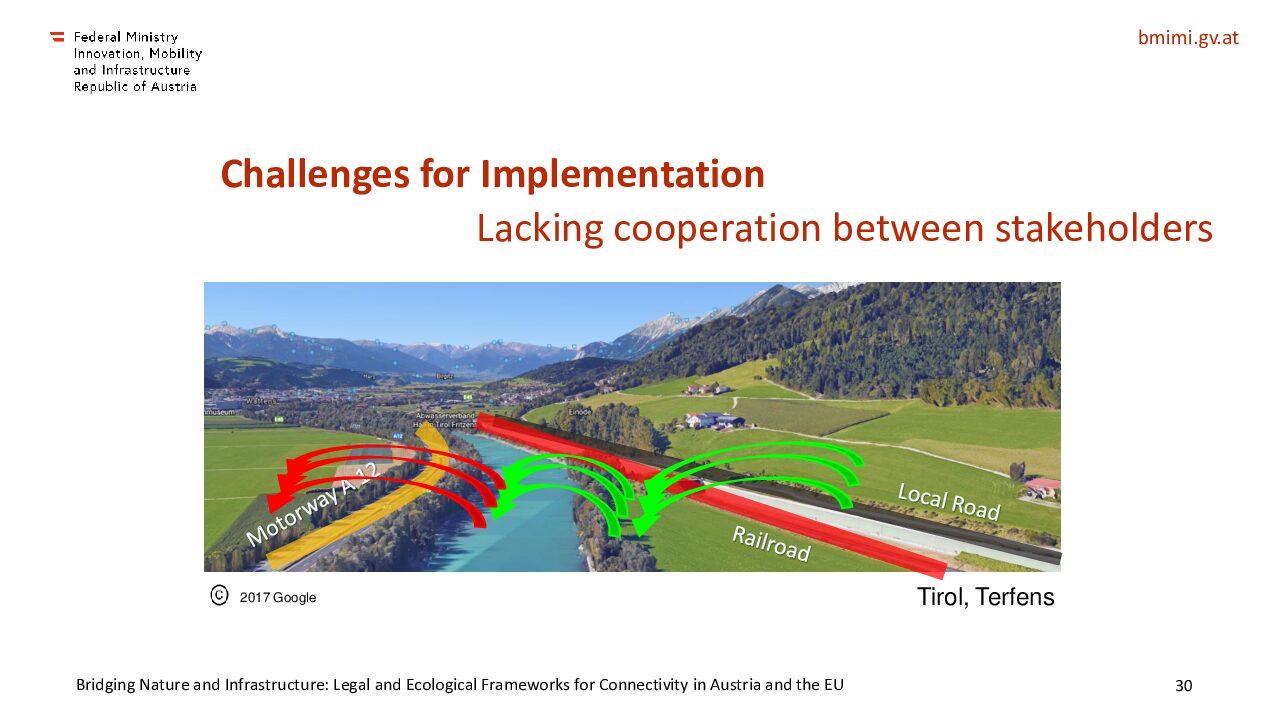

“Challenges for building wildlife crossings include site availability, e.g. landowners not wanting to sell, barriers created by other existing infrastructure, or a lack of cooperation between stakeholders,” she adds.

Austria’s environmental system splits powers between the government (federal, national level) and its nine states (regional level). Federal legislation provides procedural and sectoral frameworks; the Environmental Impact Assessment (UVP-Gesetz) Act being one such example. It is tool for transposing the European Union’s Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Directive – on ensuring environmental considerations are integrated into decision-making for major building or development projects – into Austrian law.

“The UVP requires ecological corridor assessments to be carried out during project planning,” details Ms Sattlberger. “Screening and scoping serve to identify significant land fragmentation risks early on.” In the case of motorway expansion projects, for instance, such UVPs serve to show how wildlife crossings should be integrated. Public participation in these assessments aims for transparency and ecological accountability.

Also at federal level, the RVS Guidelines (ecological planning standards) are designed to help infrastructure engineers and planners translate legal requirements into technical solutions such as green bridges and amphibian tunnels. “Harmonisation under RVS standards aligns both the railway and motorway sectors ecologically,” says Ms Sattlberger.

Regionally, each Austrian state has its own Nature Conservation Act, designed to handle species and habitat protection locally. In this context, when it comes to ecological actions like wildlife corridors, which may well span states, “coordination across governance levels is essential for coherent planning,” insists Ms Sattlberger.

The government is also counting on working with major infrastructure managers to create uninterrupted green corridors and to increase biodiversity on the widespread areas owned by infrastructure operators. In 2024, with this aim in mind, the the Ministry for Energy, Environment, Mobility, Innovation & Technology signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the three companies responsible for the country’s motorways (ASFiNAG), railways (ÖBB Infrastruktur AG), and waterways (Viadonau). An initiative that makes sense – such joint initiatives can improve overall landscape permeability – but which also isn’t without its challenges.

“Since March 2025, the political context has changed in Austria [new government] and ‘Mobility and Infrastructure’ are no longer part of the same Ministry as ‘Climate and Environmental Protection’,” points out Elke Hahn from BMIMI, also member of the governance board of Infrastructure & Ecology Network Europe (IENE), a non-profit, non-governmental network active in the field of ecology and linear transportation infrastructure.

Fortunately, despite this lack of political continuity, the three infrastructure managers solicited have nevertheless responded to calls for tenders to implement this coordinated plan.

On track with ÖBB Infrastruktur AG

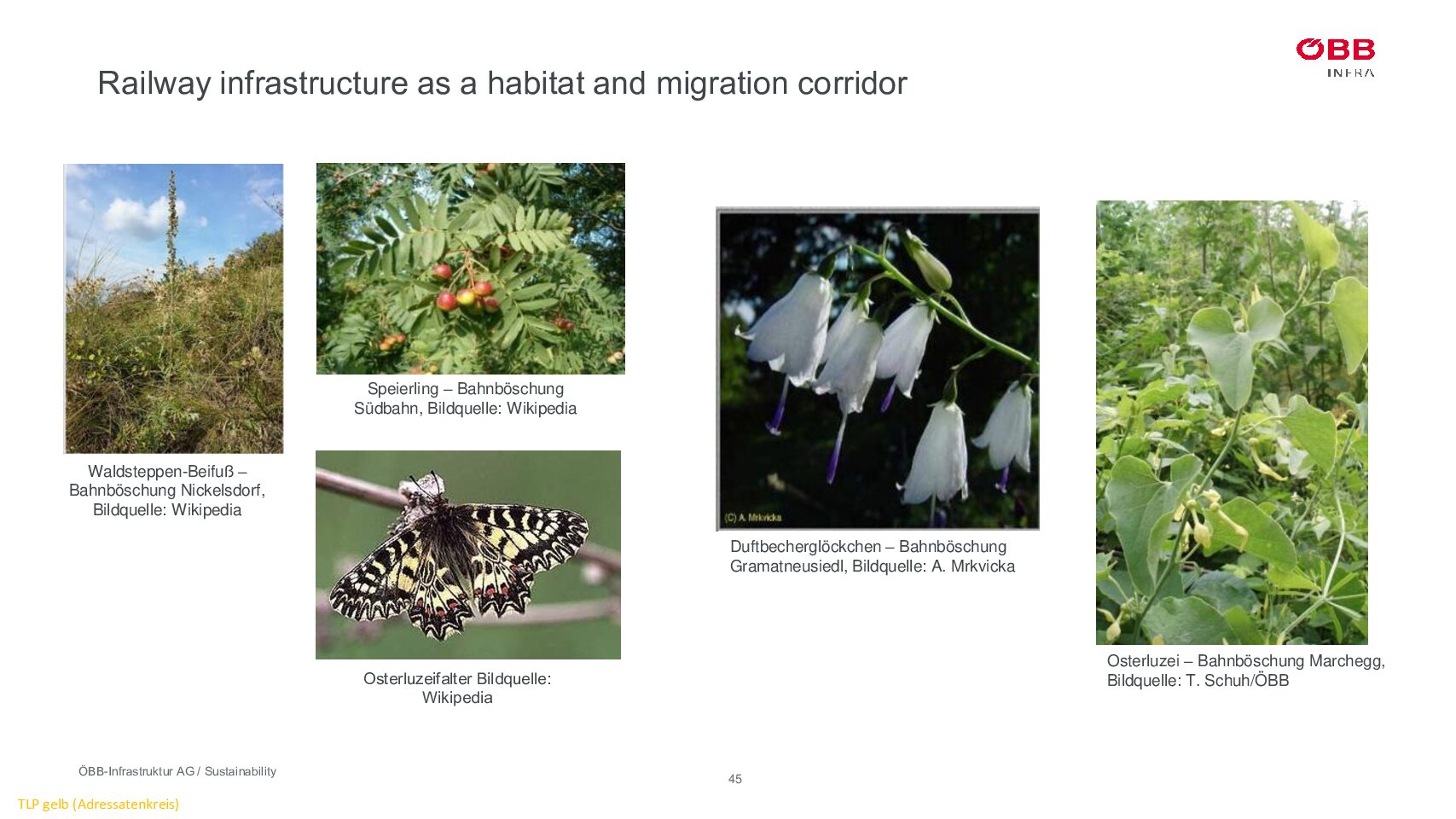

Part of the ÖBB Group, ÖBB Infrastruktur AG is responsible for building, maintaining, and operating Austria’s 5,000km rail network. As one of Austria’s largest real estate owners – managing properties of approximately 20,000 hectares of land, as well as around 3,600 buildings – it is playing a part in preserving and creating biodiversity habitats, as well as building migration corridors for ecological connectivity, and keeping Austria as green as possible.

“Such is the nature of railway infrastructure, at some specific points it is a veritable biotope,” points out Thomas Schuh, sustainability coordinator, ÖBB Infrastruktur AG. “The nose-horned viper, for instance, thrives alongside our rail tracks in certain areas because there is no human presence to disturb them.”

To present ÖBB Infrastruktur AG’s actions in the field, Mr Schuh took the Futura-Mobility delegation on an excursion to visit some key installations, together with Theresa Walter from Environment Agency Austria, and Kaja Zimmermann, sustainability management, ÖBB Infrastruktur AG.

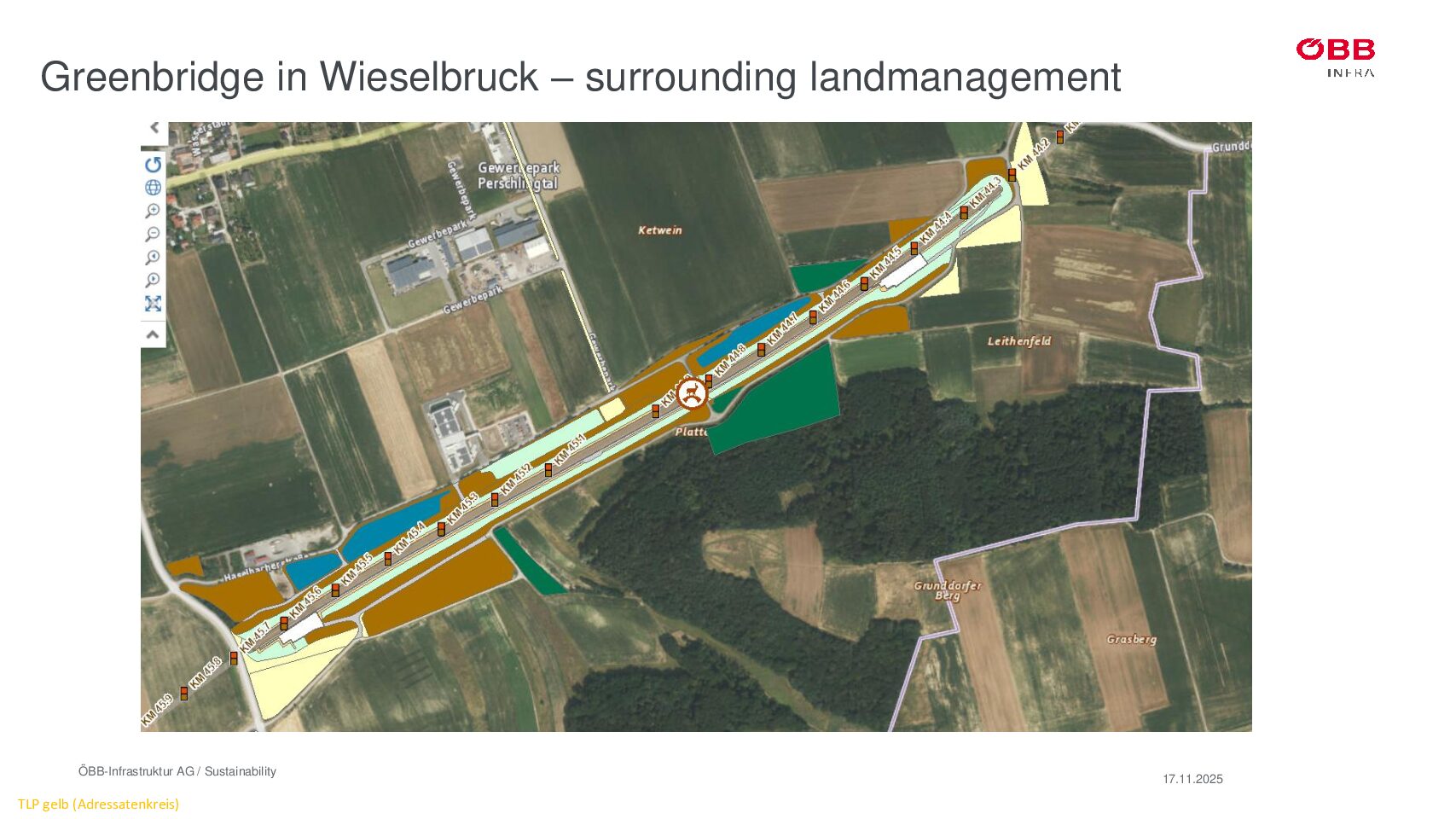

The green bridge at Wieselbruck, outside Vienna, has been in service since 2005 as a multifunctional structure for both wildlife and people. Spanning a high priority rail line running between Vienna and Salzburg, it comprises a road for use by local farmers and inhabitants and another section, planted with bushes and trees, to create a small and attractive habitat for animals to both pass through and use. “The planted area has proved really successful. We can see animal tracks that prove they are using it,” enthuses Mr Schuh. “When constructing a green bridge like this, an area to the left and to the right must be fenced in order to guide the animals to the structure,”

Nevertheless, changes to land use surrounding such structures threaten to undermine their positive impacts. Local council decisions, independent of ÖBB Infrastruktur’s ecological plans and actions, to build on surrounding land for urban or industrial developments, can and do interrupt the ecological continuity created. “In Austria it is often too easy to change the land designation,” regrets Mr Schuh. “Plus it is often difficult to acquire the land around the crossings to build them.”

“Building a green bridge like this one at Wieselbruck, which cost around 1.7 million euros 20 years ago, would today cost around three to four million euros, even using innovative construction techniques like pneumatic formed hardened concrete – bridge (PFHC-bridge) at the Koralmbahn in the south of Austria, which opened up for operation on 15 December 2025,” says Mr Schuh. “All the same, this structure worked out cheaper than building a conventional bridge, as well as saving on carbon emissions and materials.”

Given the impossibility of interrupting rail traffic (loss of service and revenue) on existing railway lines, green bridges like Wieselbruck have only been constructed for new-build projects so far. It would pose a major challenge to be built on an existing line in operation. “While it is unlikely there will be further opportunities to build more PFHC-bridges in Austria,” acknowledges Mr Schuh, “there might be in countries in Asia or Africa where new-build road and rail infrastructure is developing fast.”

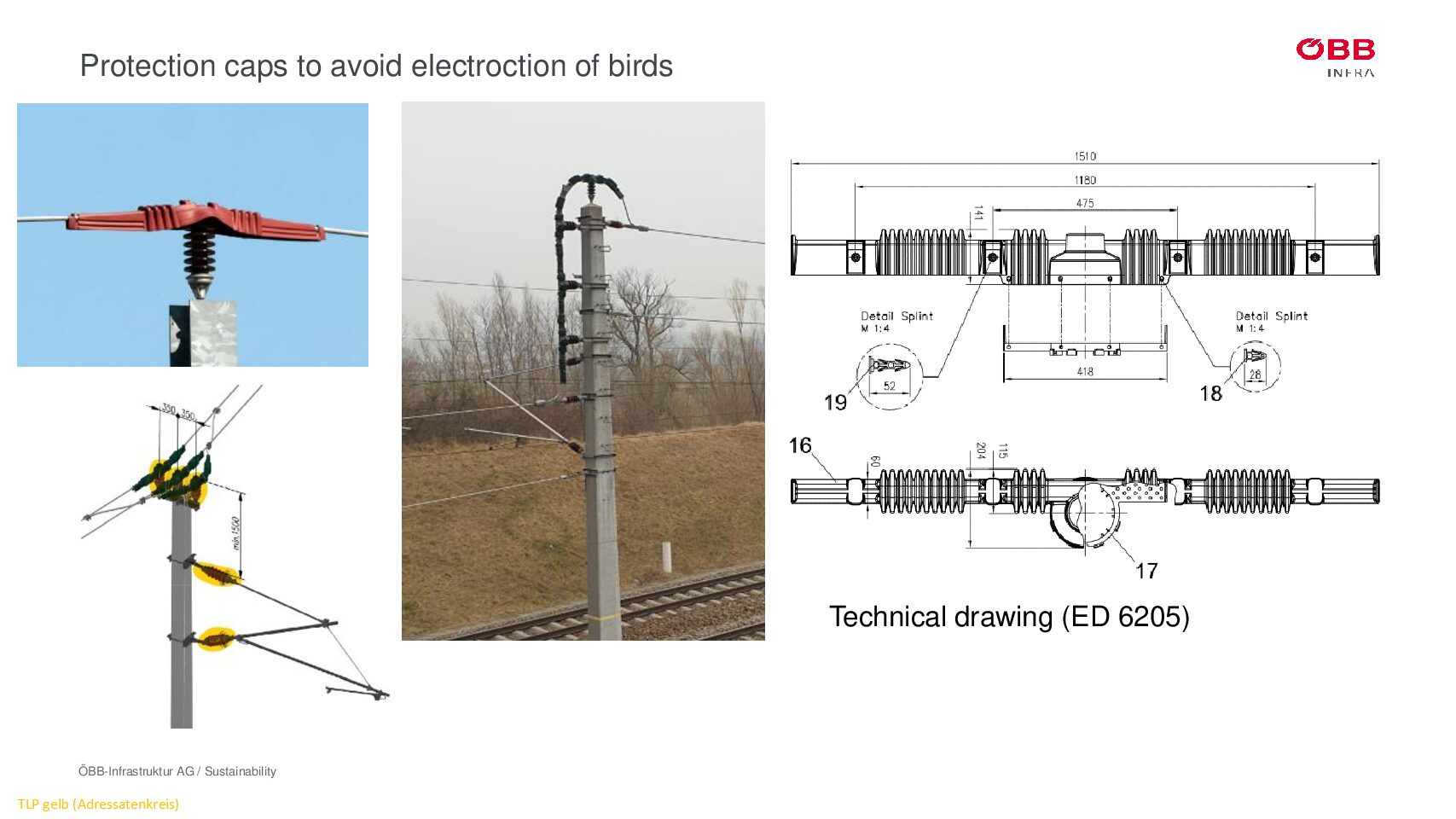

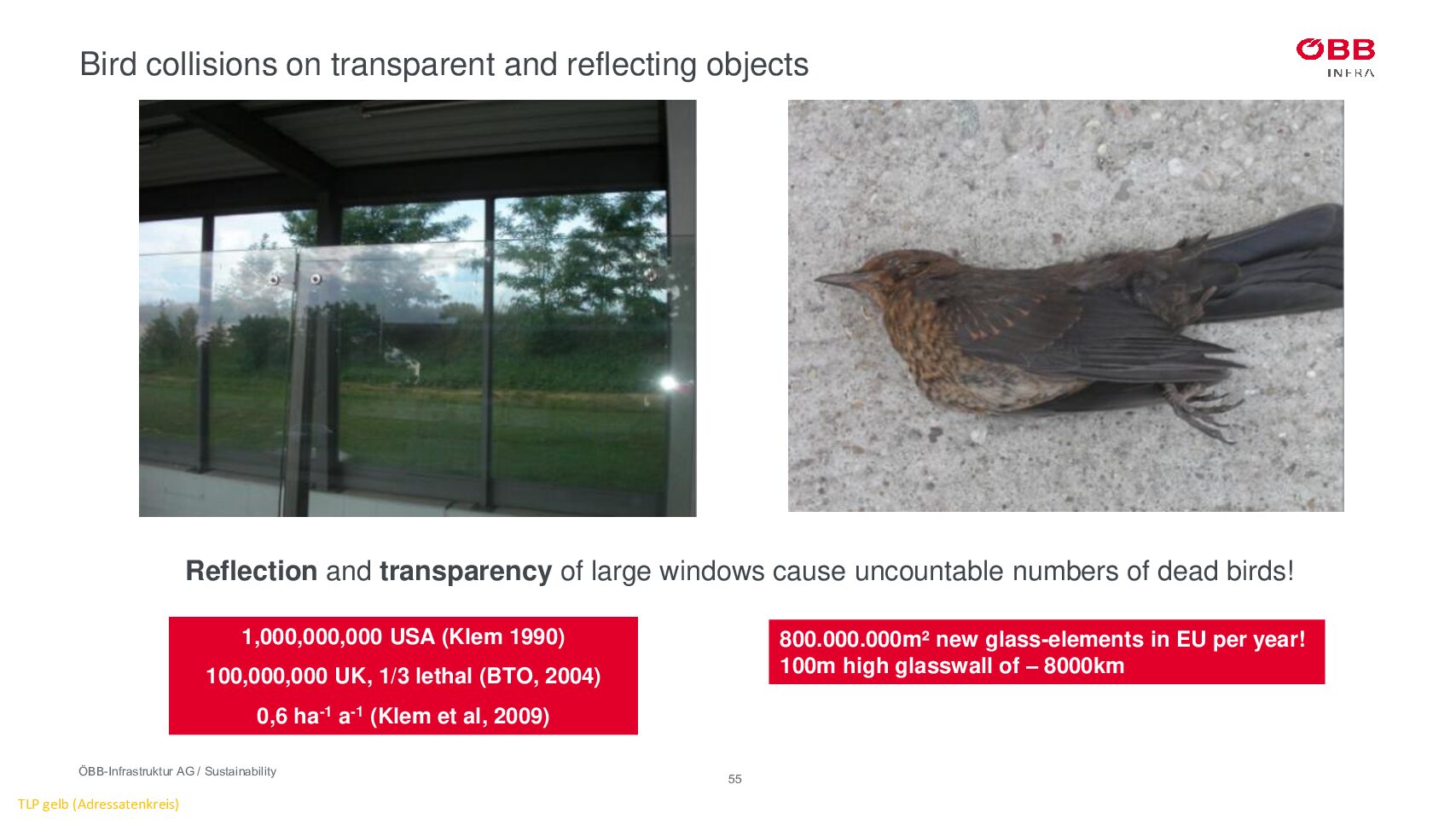

ÖBB Infrastruktur AG is also committed to protecting birds from the risks of collisions and electrocution along its rail tracks. Measures implemented include equipping catenary posts with isolation caps and attaching reflective (day and night) firefly tags on overhead wires. All these devices deter birds from perching. Another action, designed to stop birds flying into glass on the company’s buildings, has been to integrate foils into the company’s internal standards for windows and doors to make the glass more visible. “A development that helps prevent people from walking into the glass too!” adds Mr Schuh.

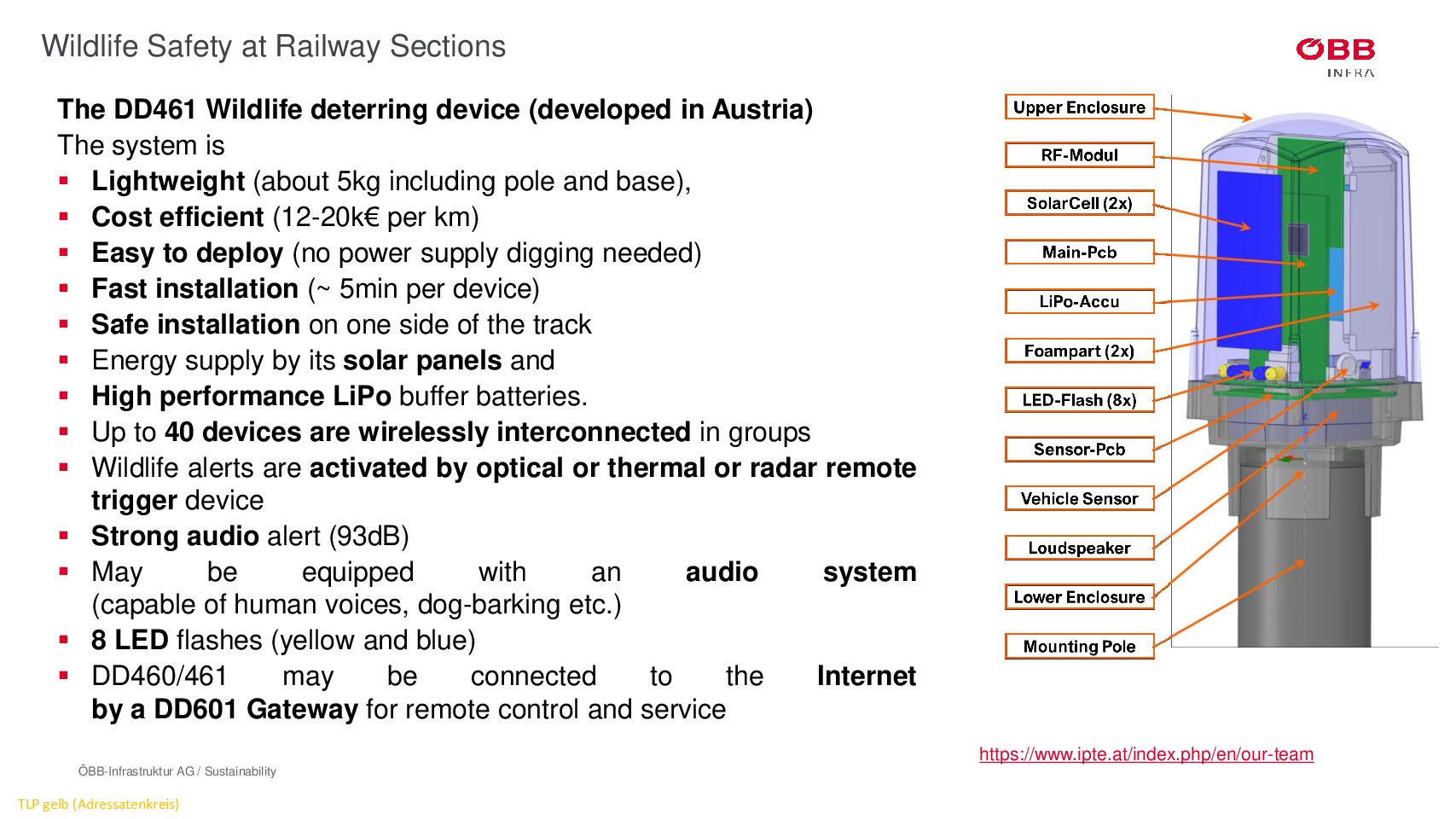

An innovation currently being tested is a trackside wildlife deterrent system. Attached to a pole, the device emits a strong audio alert to deter animals from the track when trains pass. It is a mobile unit powered by solar panels so there is no need for expensive cabling. “Note, the alert is designed to be effective but not so loud it disturbs people living nearby,” points out Mr Schuh. “Austrians are extremely sensitive to noise pollution!”

On the roads with ASFiNAG

The state-owned company ASFiNAG is responsible for operating, maintaining and building Austria’s motorway and expressway network. Its 2,266km of roads include 5,862 bridges and 168 tunnels.

As part of its Climate & Environmental Plan 2030, the company aims to boost the biodiversity of habitats along its roads, through actions such as promoting flowering areas for insects or planting native, site-appropriate and climate change-resistant plants. Wildlife corridors are another focus of attention. “Given the coverage of our network across Austria, animals cannot move around without crossing our roads,” says Ulli Vielhaber, strategy owner Sustainability, Greening, Environmental Protection, ASFiNAG. “So we must keep wildlife corridors open.”

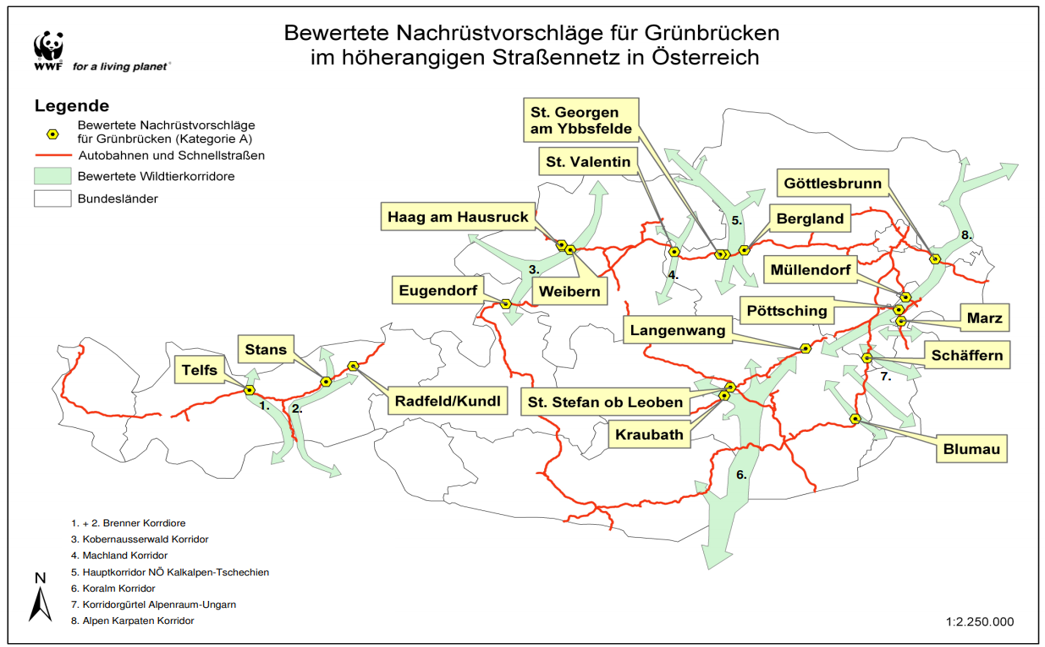

In 2005, modelling by Environment Agency Austria identified areas for retrofitting motorways to make green corridors permeable again. The findings led to an official directive from BMIMI mandating ASFiNAG to introduce green bridges every 3km on new-build motorways and retrofit 20 green bridges on existing roads up to 2026/27. To date, with just five of the 20 already built, there is still a long way to go to meet this objective.

Steps ahead

Although the country was ahead of the curve in terms of political will, regulatory and advisory tools, Austria today still faces challenges in protecting its wealth of biodiversity. Resources are clearly lacking, more regulations are needed to limit land sealing, and huge efforts are needed to coordinate actions for implementing a coherent policy across the whole territory.