🐝 Samuel Rebulard, Paris-Saclay: the vital services biodiversity provides for humans

🐝 Samuel Rebulard, Paris-Saclay: the vital services biodiversity provides for humans

“Biodiversity is often confused with nature or limited to the idea of exotic or endangered species. However, it is much more than just a collection of natural elements; it refers to all living things, omnipresent and intrinsically linked to our very existence.” The presentation by Samuel Rebulard, agricultural engineer, author, and co-director of preparation for the Life and Earth Sciences agrégation at Paris-Saclay University, on 30 June 2025, helped Futura-Mobility better understand the role of biodiversity in our lives.

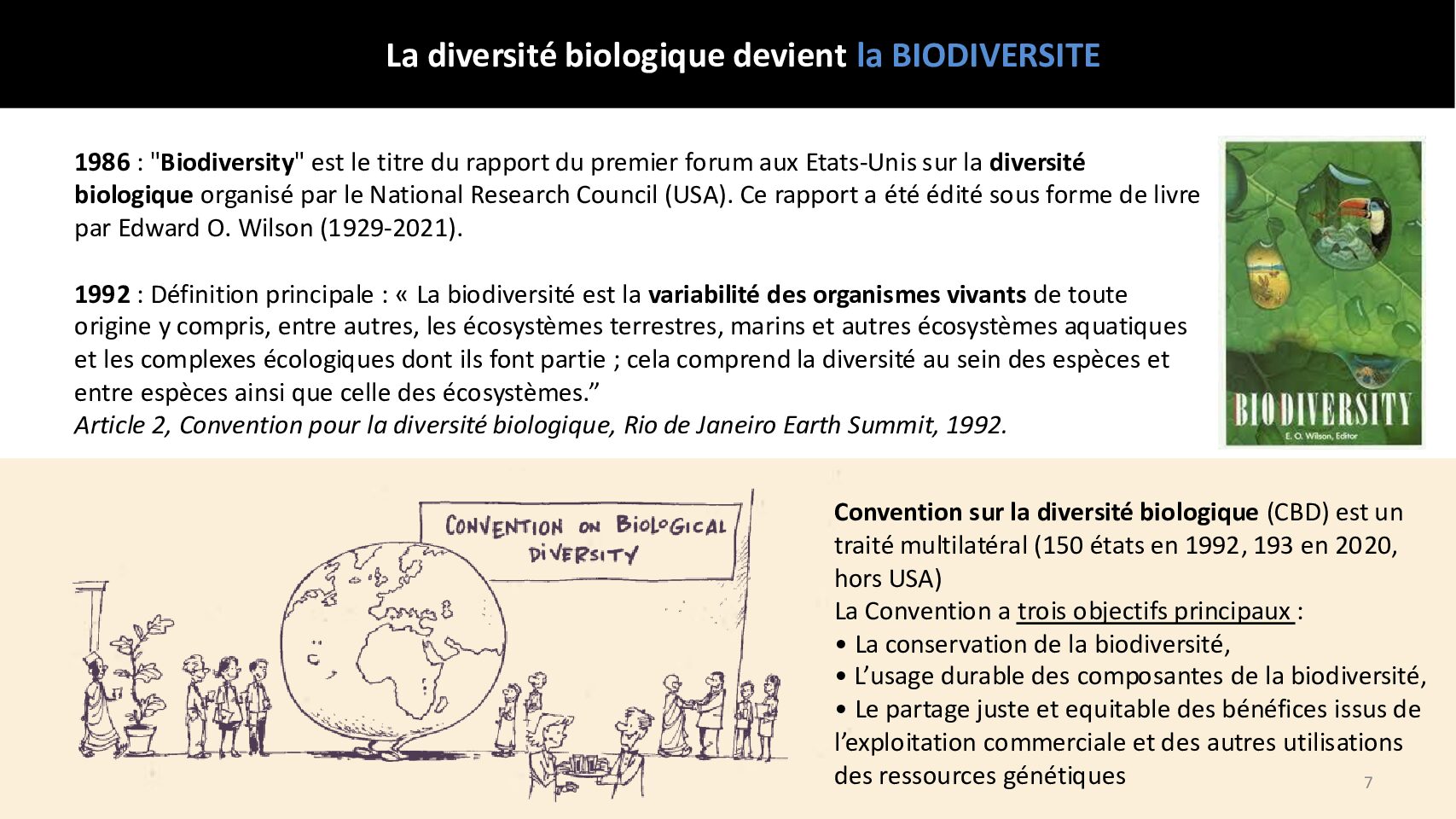

The term ‘biodiversity’ appeared in the 1980s, in a report published by the US National Research Council, to condense the concept of biological diversity into a single word. Its first consensual definition, emphasising ‘the variability of living organisms’ (see illustration below), was published in 1992 during the Earth Summit in Rio.

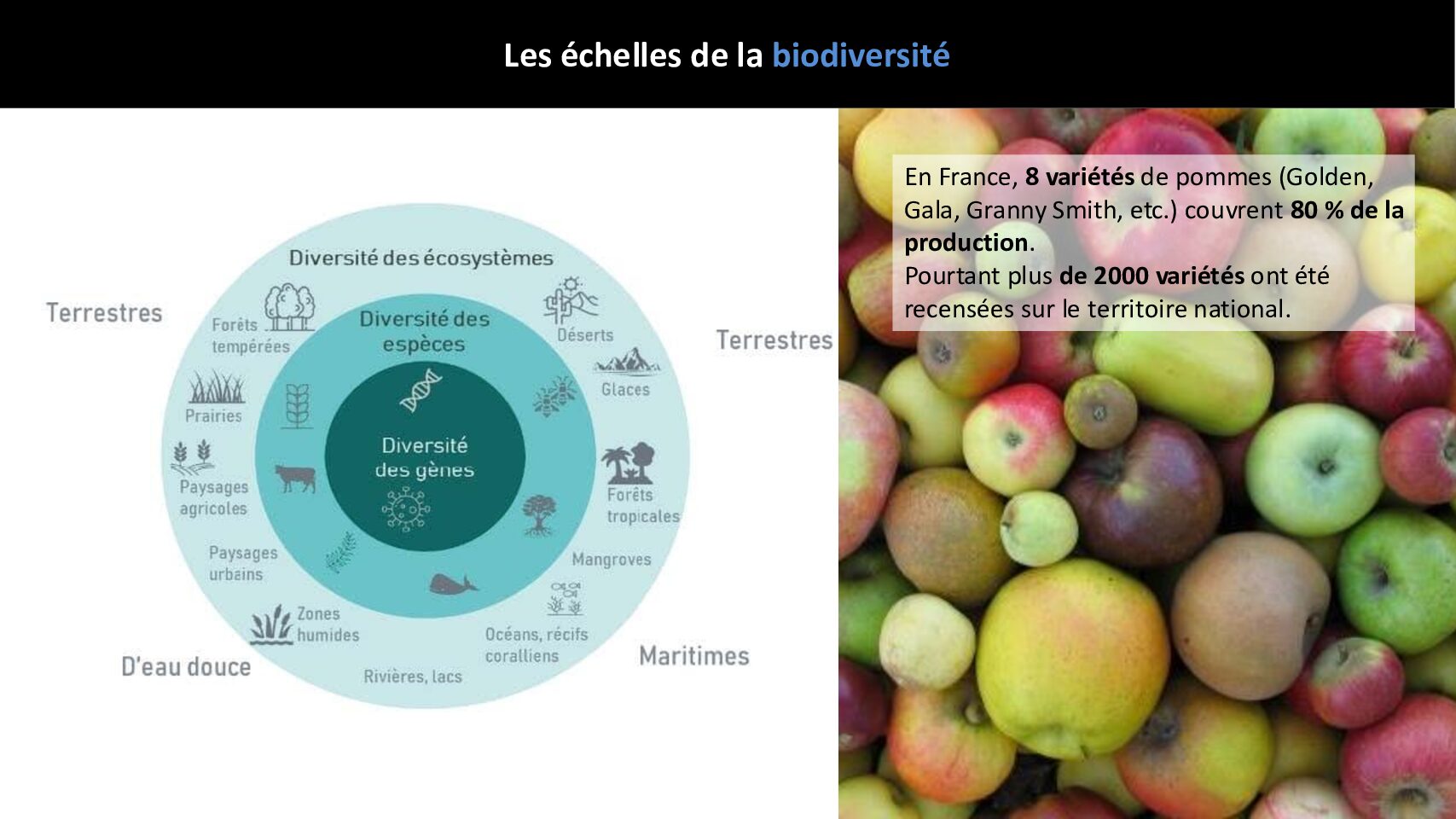

Since 1992, biodiversity has been described in several dimensions.

The genetic diversity of individuals is a valuable asset enabling all animal, plant, fungal, and bacterial populations to survive environmental hazards through random genetic mutations (chance!). The latter may or may not be maintained in subsequent generations through natural selection.

Species diversity is measured by the number of different species in a given environment, such as an urban landscape, a wetland or tropical forest. We refer to the species richness of an environment (i.e., the number of different species in a given location).

Ecosystem diversity refers to the variety of ecosystems present on Earth. Wetlands, forests, coral reefs, mangroves, or deserts — each one is home to specific living conditions and has their own unique communities of species.

Yet according to Mr Rebulard, the 1992 definition of biodiversity was missing one key element: interactions between living beings. Considering a forest merely as a juxtaposition of trees and animals ignores the complex relationships of predation, parasitism, dependence, and so forth; in other words, all the impacts the individuals living in this forest have on each other.

“You could compare biodiversity to the rivets on a plane,” explains Mr Rebulard. “Remove a random rivet, and the aircraft will probably still fly. Remove a hundred and it will probably struggle to stay in the air (depending on which ones you take off). Remove a thousand, and the plane definitely won’t fly! It’s the same with biodiversity. Overall, it is resilient… as long as the changes are minor.”

The importance of biodiversity for all

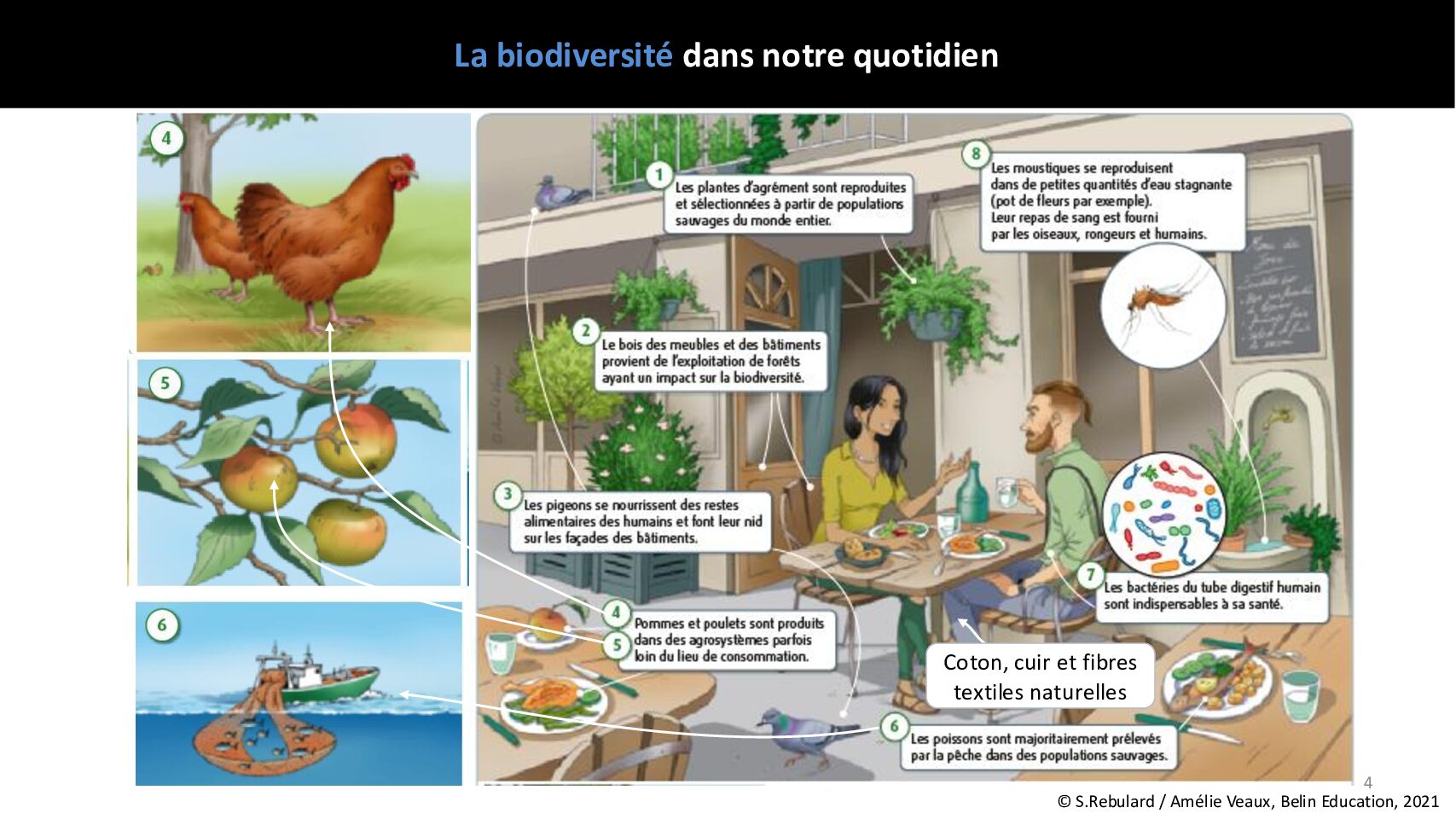

With two kilogrammes of bacteria in the gut — gut microbiota — and other microbiota on the skin, in the lungs, in the mucous membranes of the nose, etc., all of which are essential for human life, “our body is an ecosystem in itself,” M. Rebulard reminds us.

Outside the body, our food comes entirely from biodiversity. “All our food comes from domesticated plants that originated in the wild, in direct contact with local biodiversity (earthworms, aphids, soil fungi, pollinators, etc.), and therefore with dozens of species,” he explains.

Eating a pizza, for instance, brings humans into contact with agroecosystems (ecosystems modified and controlled by humans for farming purposes): olives from Italy, tomatoes from Brittany, and wheat from Île-de-France (Paris region). Samuel Rebulard does the sums: “By eating an average of ten plants at each meal and a thousand meals a year, we are in constant contact, through our food choices, with several thousand agroecosystems.” So the chemical composition of our bodies is the product of the thousands of environments that nourish us. Indeed, the carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen atoms that make up the human body come from plants that have captured these elements from the atmosphere and soil.

The materials we use in our daily lives, like wood, linen, leather, and cotton, and even rats, mosquitoes, and cockroaches — those “creatures that bother us” — are part of biodiversity. “So we are in permanent and intimate contact with biodiversity. It is everywhere, around us and inside us,” sums up Mr Rebulard.

Biodiversity crisis: indicators and causes

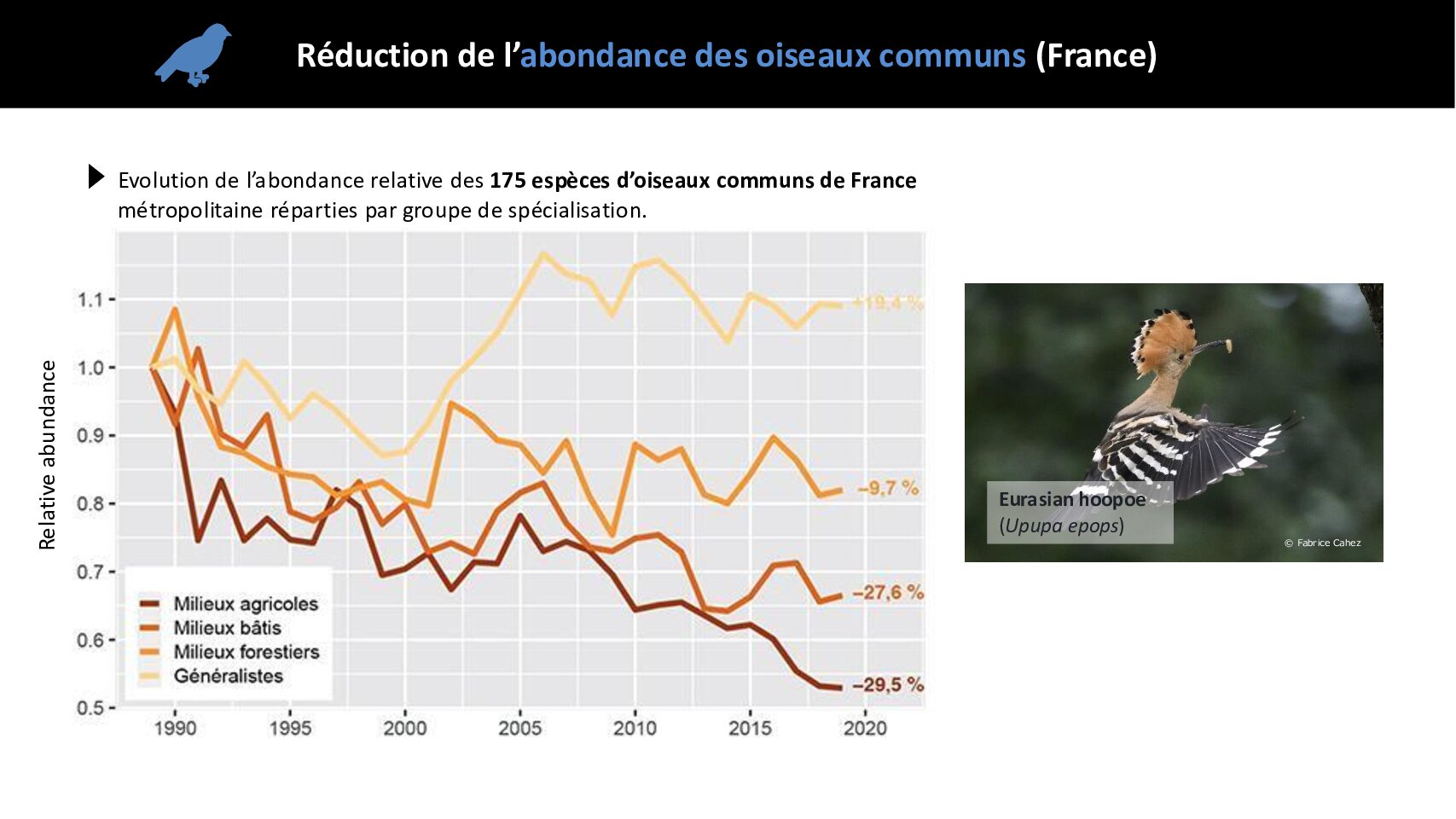

Although the exact number of species on Earth today is unknown, estimates vary between 2 and 30 million, with around 10 million being generally accepted. In this context, how can we know biodiversity is in crisis? “This crisis is real. It can be measured by observing well-known groups, such as birds, for instance,” explains Mr Rebulard.

Since 1989 in France, the STOC project has been monitoring birds nationwide by habitat (agricultural, built-up, forest, common). The data reveals the number of birds in agricultural environments (tree sparrows, yellowhammers) has plummeted by 30%, while common species (pigeons, crows, magpies) are on the rise. “This approach, which involves studying subsets, provides us with a good overview of the biodiversity crisis,” confirms Mr. Rebulard. He also stresses the importance of focusing on declines in population numbers and the shrinking distribution areas of living species, “rather than on species that have disappeared, since for them it is too late.”

When it comes to insects, quite a telling indicator of their declining numbers is the so-called ‘windscreen splatter syndrome’. Drivers have noticed that it is now possible to drive across France in the summer without stopping to wipe clean their windscreens, which was not the case 30 years ago due to the large number of insects being splattered. Considering around 75% of food crops grown worldwide depend on pollination by insects, there is indeed cause for concern.

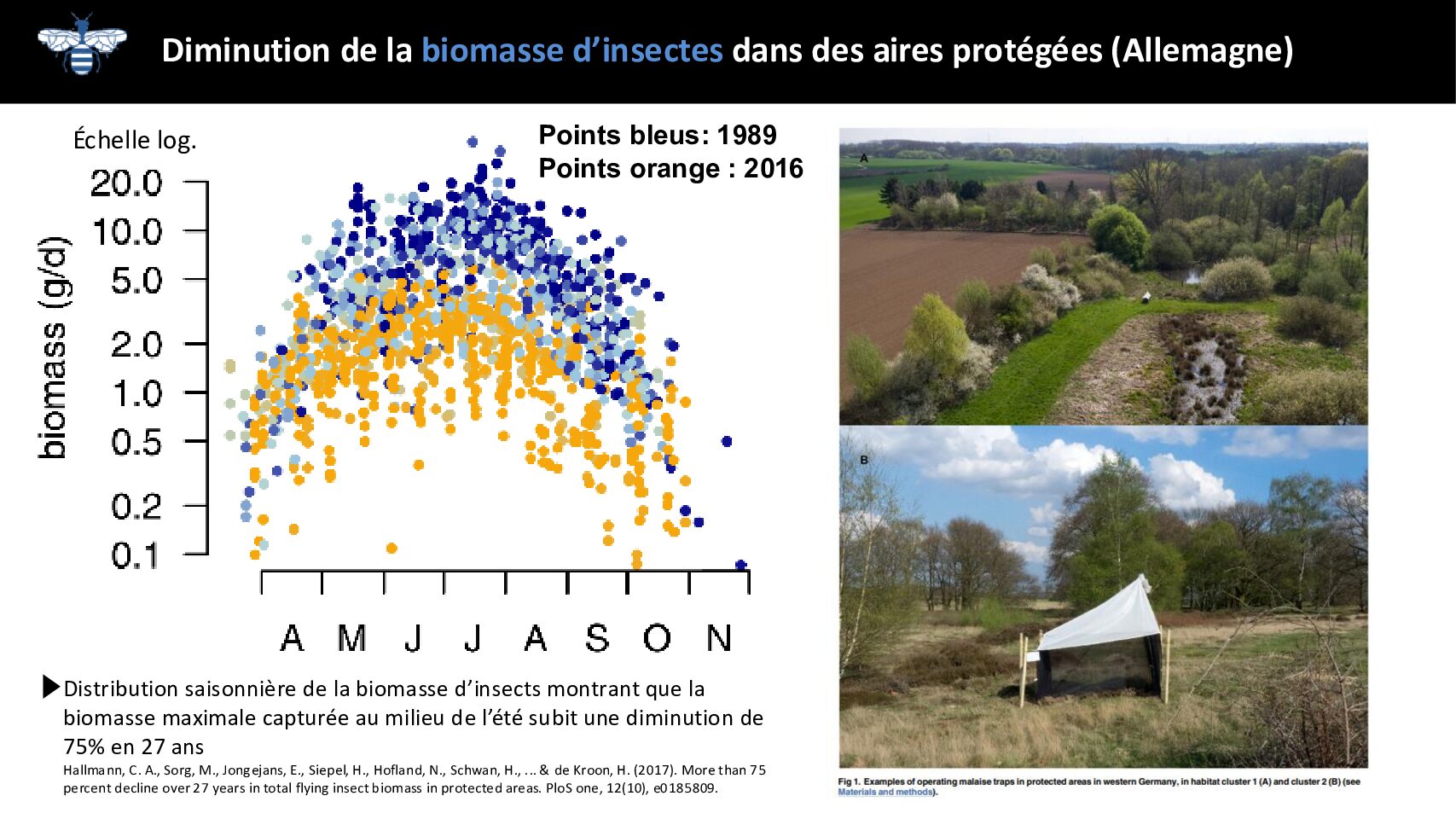

The global collapse in flying insect biomass was quantified in a German study published in 2017. Researchers set up tent-shaped traps in protected areas (see graph below). Each point represents the biomass of insects collected in a single day. The results show this biomass declined by 75% between 1989 and 2016. “We don’t need to know the exact number of insects; the biomass of insects collected is enough to see the collapse,” points out Mr Rebulard.

Disappearing species or alternations to ecosystems risk causing tipping points, i.e., thresholds beyond which degradation becomes irreversible. The destruction of a primary tropical forest or excess nutrients in a watercourse are just some examples.

Five main causes of the biodiversity crisis have been identified. Modification of habitats, like transforming forests or grasslands into cultivated fields, draining marshes, or housing developments, for instance, is by far the most important. Then there is overexploitation (overfishing, overhunting), invasive alien species, climate change, and pollution.

Building and operating linear transport infrastructure like roads destroy and alter habitats. The infrastructure also induces an edge effect, as well as contributing to soil sealing and generating pollution.

The importance of ecosystem services

Why should we care about biodiversity? For two fundamental reasons.

One is intrinsic value, the moral obligation to pass on this heritage to future generations, regardless of its direct utility. Saving a sea turtle from a net or hydrating a koala injured in a forest fire fall within this philosophical dimension.

The other is instrumental value, which focuses on the utility of non-humans in ensuring the well-being and survival of humans. “The simplistic view that only ‘useful’ species, such as those that feed us, should be preserved is wrong, because everything is connected,” warns Mr. Rebulard.

The concept of ‘ecosystem services’, which emerged in 1997, has evolved slightly over the years. Initially defined as “the benefits populations derive from ecosystems,” then as “what non-humans contribute to human survival and well-being,” and more recently as “nature’s contribution to the quality of human life,” even though the concept of nature also encompasses mineral elements like water and rocks.

Popularised in 2005 by the international Millennium Ecosystem Assessment programme and its report Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis (MEA, 2005), ecosystem services are classified into three categories:

• Provisioning services

These are the material products we derive from nature, such as food, materials, energy, and therapeutic substances. The example of the horseshoe crab is quite startling. The blood, blue, of this marine creature is used in a mandatory test in all operating rooms around the world. Since this blood coagulates on contact with bacterial toxins, it is possible to verify the sterility of surgical instruments. Overfishing of these crabs in Asia, where each one is drained to death of its blood, is jeopardising this vital service.

- Cultural services

These services provide non-material benefits. Fontainebleau forest in France, for instance, was the first protected natural area in the Western world. It was classified in 1861 for cultural reasons and given heritage value, thanks to mobilisation of the Barbizon artists and support from Victor Hugo, who defended the idea that “what centuries have built, men must not destroy.”

Studies show that the presence of green spaces in cities has psychosocial impacts on inhabitants: reduced crime, greater social cohesion, and less anxiety and depression.

Finally, in the field of science and technology, biodiversity is an inexhaustible source of inspiration. The first aircraft design was inspired by biomimicry, copying the wings of the albatross and bats. There are many examples in nature that could drive innovation: fire beetles can detect fires, some spider silk is stronger and more elastic than steel and Kevlar (the synthetic material used for bulletproof vests), corals could provide new materials for bone grafts, and so forth.

- Regulating services

Biodiversity provides many services for regulating the climate, flood control, water and air purification, soil fertility, material recycling, pest and disease control, pollination, combatting heat islands…

In 1996, in response to its deteriorating water quality, New York City implemented a regulating system. Rather than build a $6 billion water treatment plant, the city purchased and reforested agricultural land in its Catskills watershed for $1.5 billion. This approach has naturally restored the water quality. The more a watershed is forested, the less the cost of water treatment.

In France, the Lake Aydat wetland was restored to absorb agricultural pollutants from the watershed. This meant people could once again swim and fish in the lake. The wetland provides a natural service that costs much less to maintain than introducing water treatment infrastructure upstream of the lake.

Wooded areas in cities, such as the Bois de Boulogne in Paris, create a microclimate by lowering temperatures by several degrees during heat waves, thanks to the evaporation of vast quantities of water by trees: “a 200-year-old oak tree evaporates 40 tonnes of water a day.” Trees also help prevent flooding by improving water infiltration into the ground, due to their role in enriching soil with organic matter (which acts like a sponge), and structuring it through their root systems.

Dung beetles (coprophagous beetles), which feed on excrement, provide a fundamental recycling service for (fecal) matter by digesting and burying organic matter in the ground. In Australia in the 1960s, native dung beetles shunned the excrement produced by cows and sheep introduced to the island continent by humans. The catastrophic accumulation of dung from these ruminants resulted in the loss of one million hectares of grassland a year! In 1967, African dung beetles had to be introduced to resolve the issue… “something we wouldn’t do today because it generally creates other problems,” tempers Samuel Rebulard.

Another example of recycling, in India. Cattle carcasses are left to rot and usually, vultures feed on the flesh and so get dispose of it. But the presence, in these carcasses, of an anti-inflammatory drug administered by humans that is highly toxic to vultures, has caused a 98% decline in the vulture population in 20 years! Stray dogs, which are not affected by the drug, now have food available with these carcasses and their population has consequently exploded. As carriers of rabies, dogs have caused the deaths of an additional 30,000 people per year. This example illustrates the ‘One Health’ concept, which recognises the deep interdependence between human health and the health of ecosystems.

Another example of regulating can be found in the United States, where reintroducting wolves to Yellowstone National Park in the 1970s led to a cascade of positive effects. By hunting and limiting the population of deer that rub against trees and eat their young shoots, especially along the riverbanks, wolves have enabled trees to grow there again. The return of a riverside forest has benefitted beavers, which regulate water flow with their dams, thereby limiting bank erosion. Forest birds have returned, the salmon population has increased, and even bears have returned. The wolf is a so-called ‘umbrella’ species: protecting this animal benefits the entire ecosystem.

To combat pests (living organisms that damage crops or harvests) and diseases, regulating ecosystem services also play an key role. In France, nocturnal birds of prey (owls, eagle owls) regulate vole populations. Their absence, caused by degradation of their natural habitats, results in vole infestations that damage crops, resulting in the use of harmful chemicals.

Toads and swallows, natural predators of mosquitoes, are another example. They can reduce these pests to a non-problematic level, “thus demonstrating how managing ecosystem services is an effective solution,” adds Mr. Rebulard.

Monetising ecosystem services

According to figures from the study The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (1997), the economic value of insect pollination is estimated at $153 billion a year (10% of total global agricultural production). The destruction of coral reefs, the backbone of a multitude of industries, starting with fishing and tourism, represents a loss of $30 to $172 billion anually. “This study recommends investing 1% of global GDP per year to avoid much greater losses in the long term,” warns Mr. Rebulard.

Technological solutions and nature-based solutions (NbS) are within reach, “but it is essential to distinguish between them depending on the issue to be resolved,” explains Mr. Rebulard. “Technology is vital for tackling plastic pollution, as nothing has yet been found in nature that can do this. Yet when it comes to carbon storage in biomass and soil, pollination, regulating water quality, flooding and crop pests, nature does the job very well, often at much less cost than technology-based alternatives.”

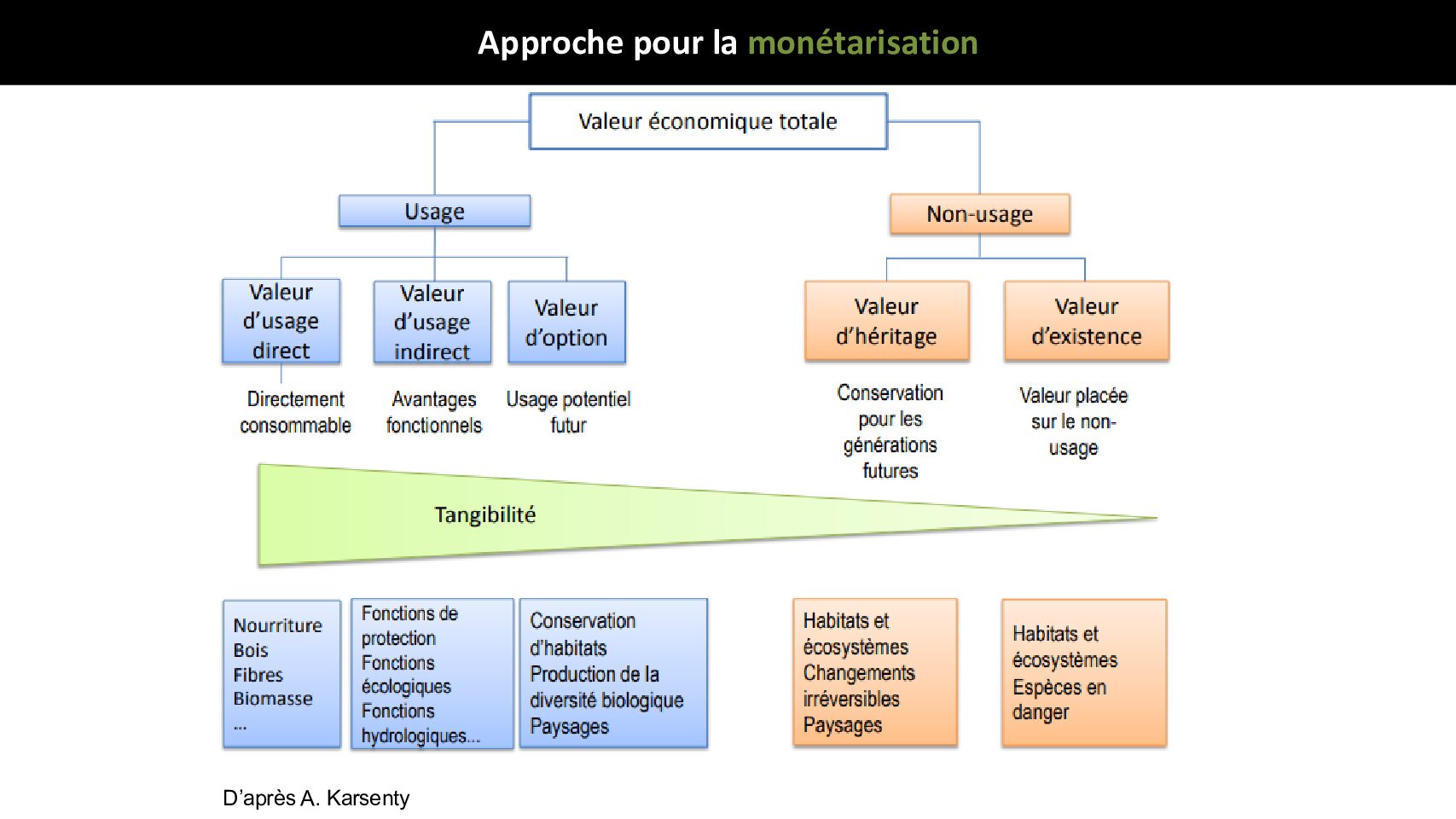

Faced with the erosion of biodiversity, monetising ecosystem services leads to prioritising their benefits by estimating their use values—‘directly consumable’ or representing ‘potential future use’ — or their non-use values — ‘conservation for future generations’ or ‘existence’ (see illustration above).

Based on the principle of payments for ecosystem services (PES), providers of such services, like farmers, who promote biodiversity, carbon storage, or natural water filtration through their land management practices, are remunerated. These PES are economic incentives to finance the sound management of ecosystems and restoration of natural capital by humans for humans.

In France, to preserve water catchments, Volvic pays farmers to adopt good practices in the fight against voles that avoid using chemicals.

In Tasmania, the Australian government uses an PES system to compensate private landowners for their actions (which they themselves propose ) to conserve the ecological value of forests. The total budget is distributed among landowners through reverse auctions, putting them in competition with each other.

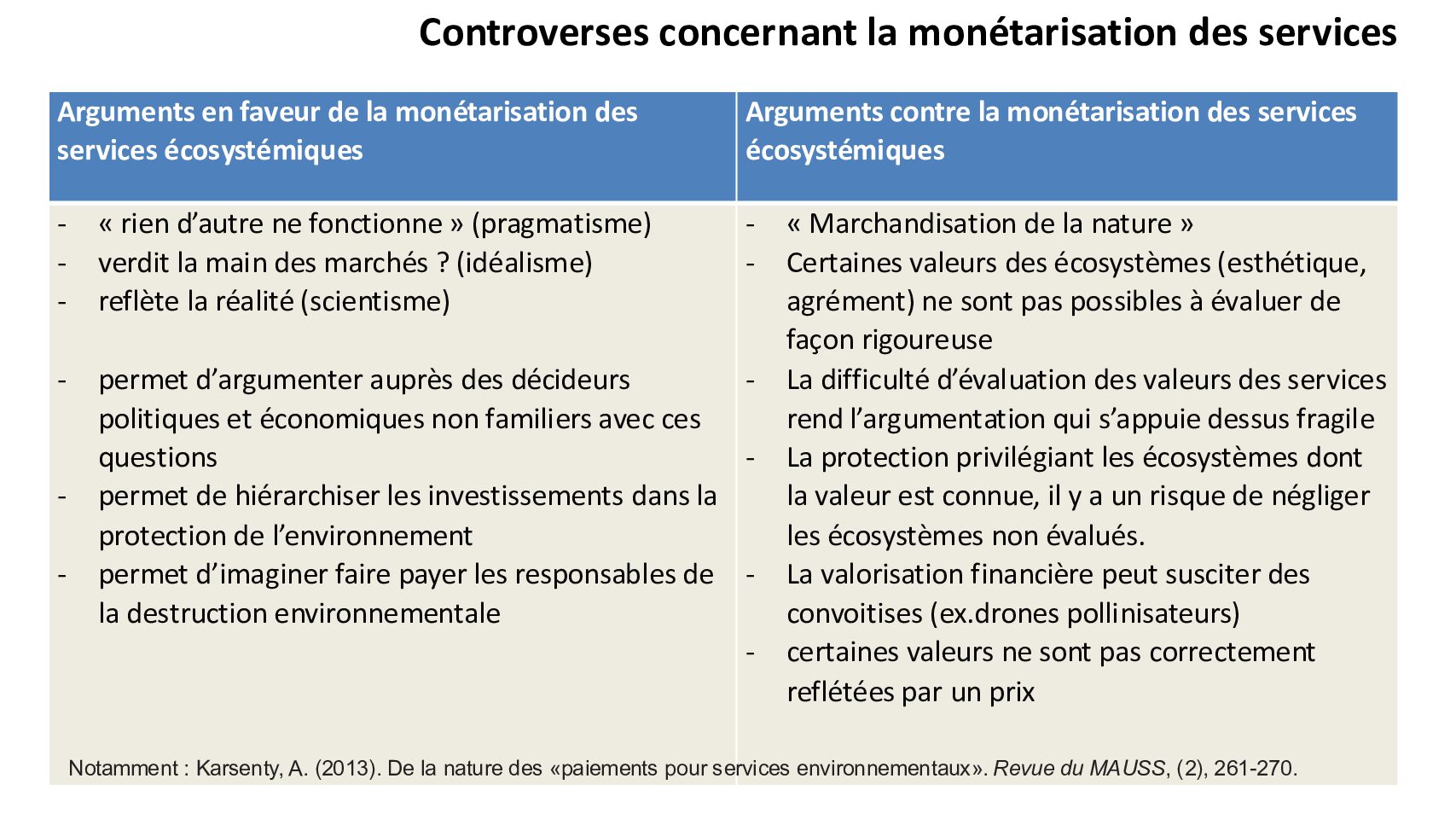

“In practice, PES concern a limited number of services, notably water quality, biodiversity conservation, carbon sequestration, and landscape beauty, and function for local services,” explains Samuel Rebulard. “Furthermore, financial valuation can arouse greed and lead to privatisation of certain ecosystem services.”

Indeed, most assessments focus on only part of the values associated with these services, mainly those related to ‘use’. This is why, today, there is debate between economists and ecologists over methods used for the financial valuation of ecosystem services.

Biodiversity and humans: inseparable

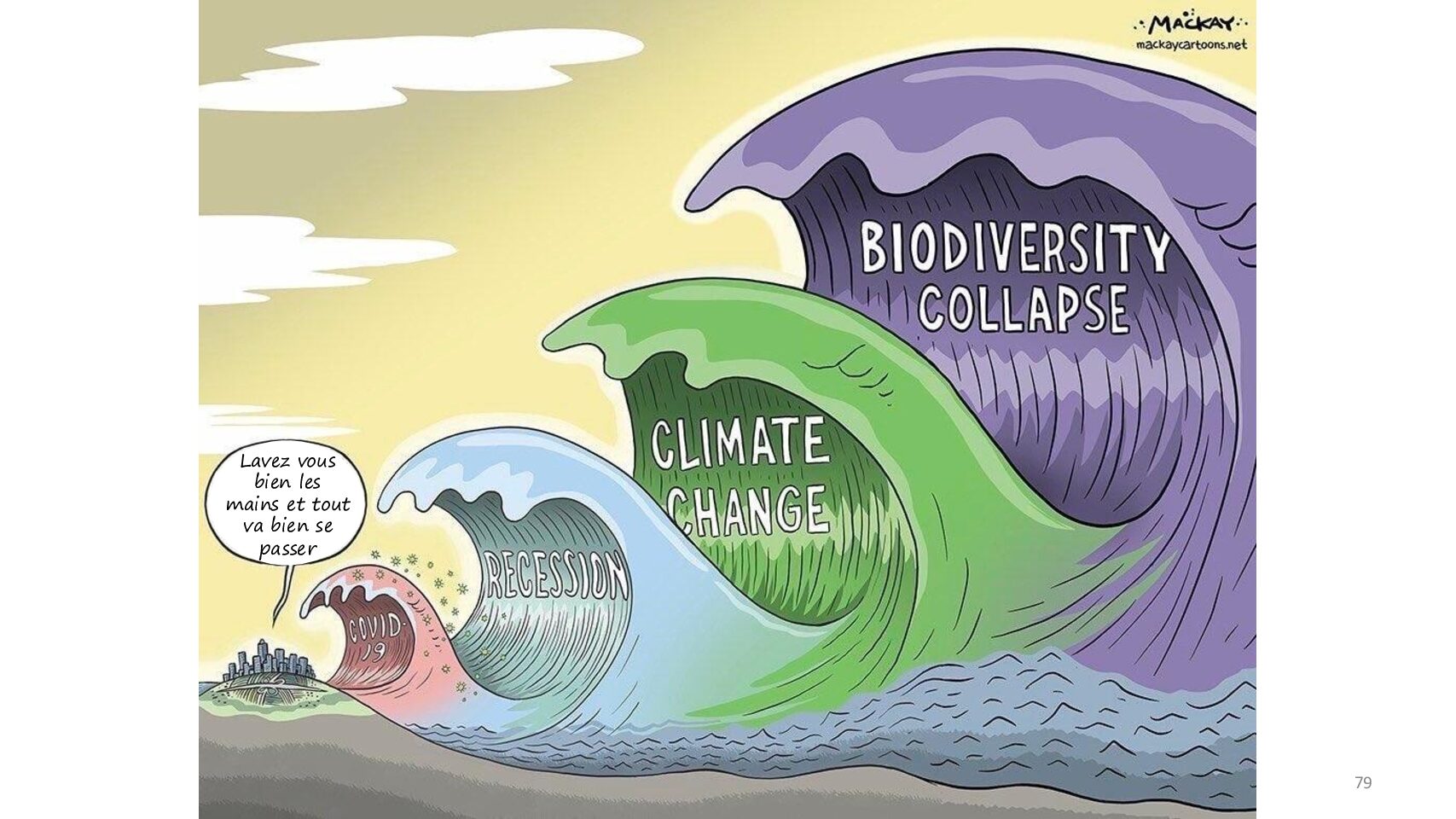

Humans derive vital benefits from biodiversity. However, even though biodiversity loss has consequences at least just as serious as climate change, it is more difficult to understand and address. The greenhouse effect, with its causes, almost unique indicator, and already visible consequences, is easier to grasp than biodiversity, which covers a multitude of situations that are not easy to comprehend and explain, and whose disruptions often have consequences that are difficult to grasp at first glance.

Yet just like fighting climate change, tackling biodiversity loss on the planet is everyone’s responsibility — businesses, citizens, and public authorities — and it is urgent we take serious action.

“If trees were Wi-Fi hotspots, we would plant them everywhere! Unfortunately, they only provide oxygen, fruit, rain, cool shade, protection from the wind, climate regulation, and flood control,” concludes Samuel Rebulard wryly.

Articles similaires:

Il n’y a pas d’article similaire.