🇦🇹 The importance of urban and mobility planning in Vienna

🇦🇹 The importance of urban and mobility planning in Vienna

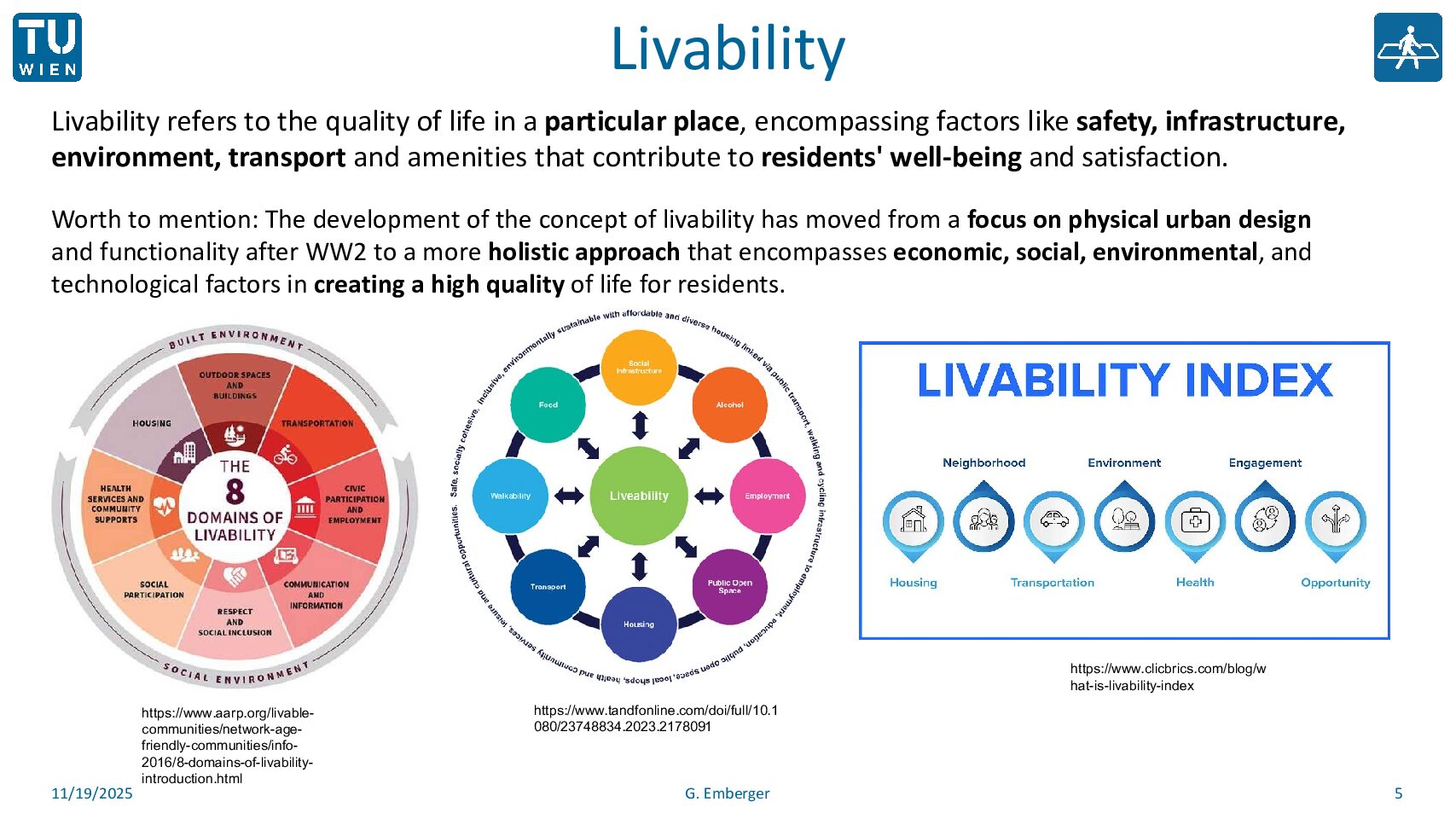

Vienna, the capital of Austria, is home to approximately two million inhabitants. In 2025 it ranked the second most liveable city in the world, after Copenhagen, having been listed number 1 from 2022 to 2024. A plaudit confirmed by over 90% of residents, who say they like living in the city. This liveability is largely linked to its good public transport and commitment to public welfare.

The well-developed public transport system has buses, trams, and trains at its heart, linked up to cycling lanes and pedestrian areas. The network is continuously expanding, and a major metro project is ongoing. Vienna has also set an ambitious goal to achieve climate neutrality by 2040. This commitment drives a strategy that prioritises sustainable planning and a steady increase in the modal share of public and active transport (walking and cycling).

During Futura-Mobility’s field trip to Austria, in November 2025, the delegation learned more about what makes Vienna so liveable. How is governance, urban and transport planning, past and future, keeping the city on its sustainable path?

Today, much of Vienna’s status as a leading global city for liveability is down to it being a pioneer in urban and transport planning, recognising early on that active mobility modes and public transport are key to good urban living. Indeed, the first Transport Masterplan, drawn up over 40 years ago, engineered a paradigm shift in transport from predict & provide for car traffic to promoting more sustainable mobility. This Masterplan is revised every 10 to 15 years.

Another contributing factor is the continued presence of trams. During the car boom of the 1950s, Vienna, like many other cities worldwide at that time, was keen to remove its tramway system to make way for the automobile. “But since we Austrians were too slow, not all the trams in Vienna were removed!” explains, with a touch of humour, Günter Emberger, head of the Research Unit for Transport Planning and Traffic Engineering at TU Wien. “This goes to show that not being the fastest sometimes has its advantages.”

The modal split in Vienna is currently 30% walking, 11% train, 34% public transport, and 25% cars, compared to 17% walking, 7% train, 18% public transport, and 58% cars for the rest of Austria. Importantly, the city has won its high share of public transport without losing shares of active transport modes (walking and cycling). A feat achieved in part by the introduction of on-street parking fees since 1993 to dissuade car use.

Another positive is the integrated ticketing system for public transport. The price of the annual ticket for unlimited travel in Vienna and its surroundings, €365, has remarkably remained the same since 2012 (due to rise to €461 on 1 January 2026). Over one million people, half the city’s population, use this ticket to get around.

Traffic has been calmed in 80% of the streets with 30km speed limits, which has resulted in fewer accidents and less noise. The city’s steady process to increase cycling, e.g. through efforts that include high-quality infrastructure like the Dutch-style Argentinierstraße, has resulted in the network growing from 11km in 1977 to 1,780km today.

Vienna has a unique governance structure. It functions both as a municipality and one of Austria’s nine provinces. “This status gives greater leeway in terms of passing legislation, since unlike other cities in Austria, Vienna doesn’t have to collaborate with its provincial states,” says Julian Kerry, international affairs & strategic alliances at Urban Innovation Vienna, the climate and innovation agency of the City of Vienna.

Surprising perhaps, but true, the city has agricultural land in production within its boundaries! It is either owned and farmed privately, or by the City of Vienna, which also owns vast forests in Styria and Lower Austria that supply water exclusively to the city. “Vienna aims to own as much of its infrastructure as possible, from education, energy, healthcare and housing to public transport, waste management, and the water supply,” explains Mr Kerry. “And I believe this is the right path to staying agile. By owning the real estate and utilities, you can also govern them. If privatised, it is harder to influence them. You can write laws, contracts, and so forth, but it’s far easier to manoeuvre these services if you own them.”

This desire for ownership and control is indeed reflected in the affordable housing model. The City of Vienna directly owns the most social housing stock of any city in Europe, with approximately 220,000 flats. There are also 200,000 co-operative homes built with municipal subsidies. All in all, a quarter of Vienna’s population lives in social housing. Furthermore, recent zoning laws mandate that two-thirds of new developments on plots over 5,000 m² must be subsidised units, ensuring affordability keeps pace with population growth.

Urban and transport planning for today, and tomorrow

Despite its considerable milestones, Vienna cannot afford to rest on its laurels. Its population of 2,005,500 and growing is putting pressure on existing services and infrastructure.“Vienna has historically been a major destination for migrants,” points out Julian Kerry. “For instance, since the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989, the population has increased by 300,000 – due not only to our high birth rates but also migration from neighbouring countries”. By 2030, the figure is expected to exceed the historical population high (1910) of 2.1 million inhabitants.

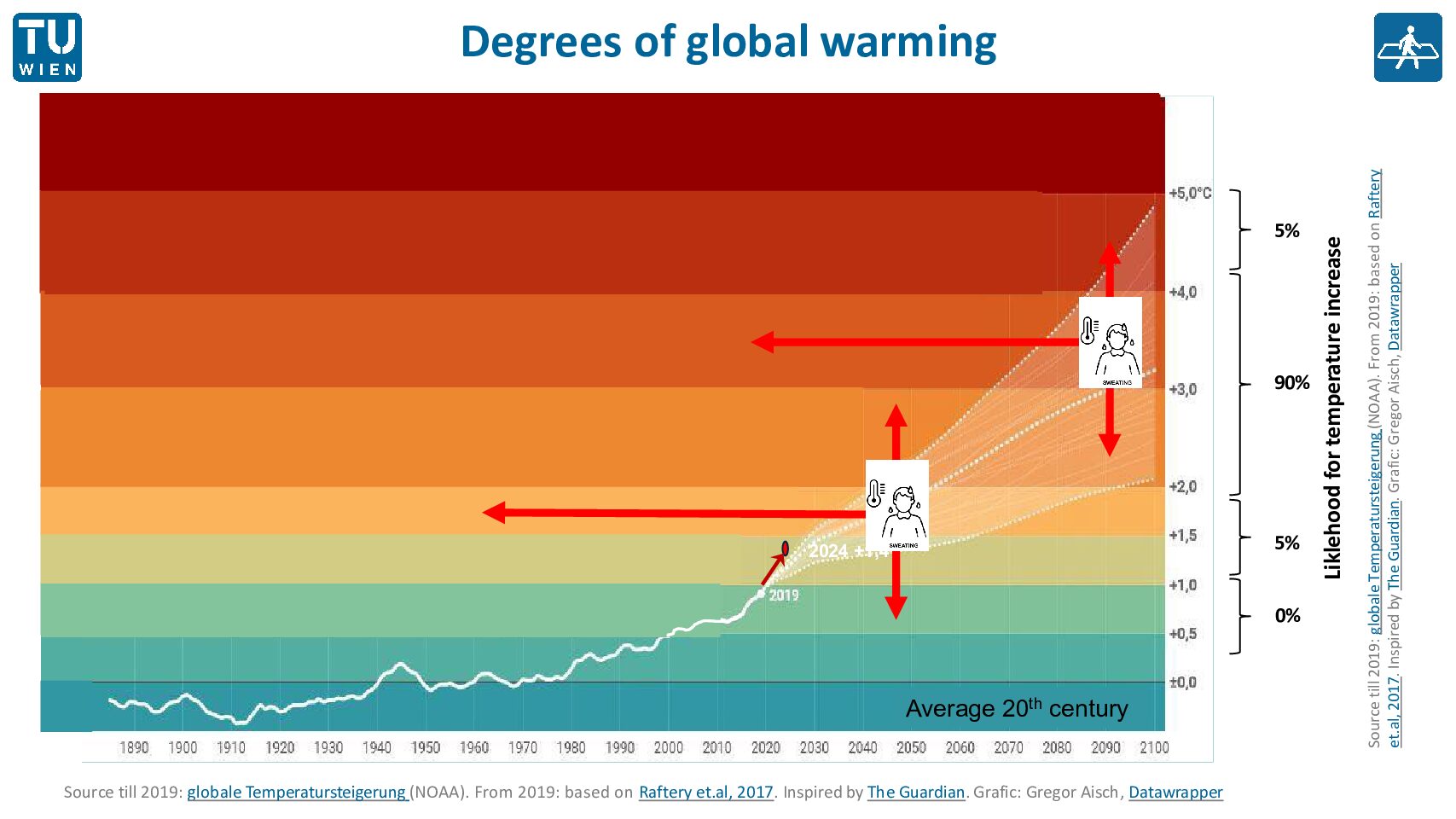

In parallel, the global climate crisis is another pressure that can hardly be ignored. “The world has already reached the 1.5°C increase in global warming. All future investments in transport infrastructure must reduce CO2 emissions!” drives home Mr Emberger. “This calls for immediate action!”

Given this context, and as part of Vienna’s 2040 climate neutrality target, “the city’s goals include expanding the public transport network, adapting to climate change, and developing the regional network of sustainable mobility,” explains David Hees, urbanist & mobility expert, Urban Innovation Vienna. Decision-making and planning in these directions is guided by plans like the Smart Climate City Strategy which seeks to provide a ‘high quality of life for everyone in Vienna through social and technical innovation in all areas, while maximising conservation of resources’.

Another support is the recently released (September 2025) Der Wien-Plan–Stadtentwicklungsplan 2035, which centres urban development on brownfield sites, e.g. the former Aspern airfield (closed in 1977) and railway land, while simultaneously prioritising a dense, mixed-use structure and creating green corridors to link major natural areas like the Vienna Woods: part of the city’s (legally protected) green belt, this ‘green lung’ encompasses seven Viennese districts.

“Vienna is very dense. Parts of the inner city, in particular, are extremely dense and don’t have much green space,” expands Mr Hees. “But the city is surrounded by large green spaces and for the past 10 years we have been working to link them up with green corridors.”

To keep the growing city on the move, the metro system, which together with the S-Bahn forms the backbone of a comprehensive public transport network, is being expanded. Two new lines are soon to open: the U5, the city’s first driverless system, is due to be completed in 2026, followed by the modernised U2 in 2028. Part of these construction costs are funded by the City of Vienna U-Bahn tax imposed on companies with employees in the city: these firms must pay €2 per employee per week.

In parallel, a goal to reduce the modal share of car traffic to 15% (currently around 25%) by 2030 is based on implementing strategic push and pull measures. On the ‘push’ side, extending the city-wide parking fee zone in 2022 – where only short-term, paid parking spots are available – has put more financial pressure on people to rethink their mobility behaviour. “Over the past 10 years, car ownership has been decreasing in Vienna, while increasing in the rest of Austria,” points out Mr Kerry. “And according to the latest survey (2025) by the Department of Urban Planning, 27% of respondents (living in Vienna) who owned a car said they could imagine not having one anymore.”

On the ‘pull’ side, measures include implementing Superblocks (Supergrätzl) – an approach that defines areas in the city (blocks of housing) with a traffic-calmed core, i.e. motorised through traffic is prevented and the focus is on pedestrian and bicycle traffic, as well as close links to public transport. Another course of action is the ‘Out of Asphalt’ programme that unseals (removes concrete claddings) and reclaims street space for active mobility and green spaces. Street infrastructure is also being designed to encourage walking, for instance, by narrowing cross-sections for safer, easier crossings.

“Getting people on board the cooperative process, is key to greening the city,” points out Mr Hees. “Residents and shop owners tend to resist changes at first, then discover the benefits. Indeed, we also have bottom-up projects whereby inhabitants change their streets themselves.” An example of such a community initiative is the Grätzloase. Designed to empower residents to propose changes to the way their streets are used, this City of Vienna support structure offers up to €4,000 in funding to convert parking spots into small community gardens or seating areas.

For people living in the outer reaches of the city, a research project called WienMobil Hüpfer is currently running to provide ride sharing. On two test sites, electric shuttle buses operate between public transport stations or for direct point-to-point connections. Users book on a dedicated app and are picked up at one of 500 virtual spots.

With so many efforts to strengthen and develop sustainability underway, it may come as a surprise Vienna has no immediate plans for autonomous vehicles. But, as Mr Hees points out, “shifting private traffic to public transport is currently the city’s number one priority for mobility.” Keen to ensure automated mobility supports, rather than competes with public transport, the City of Vienna, which published a position paper in 2024, is taking its time to bring this technology on stream.

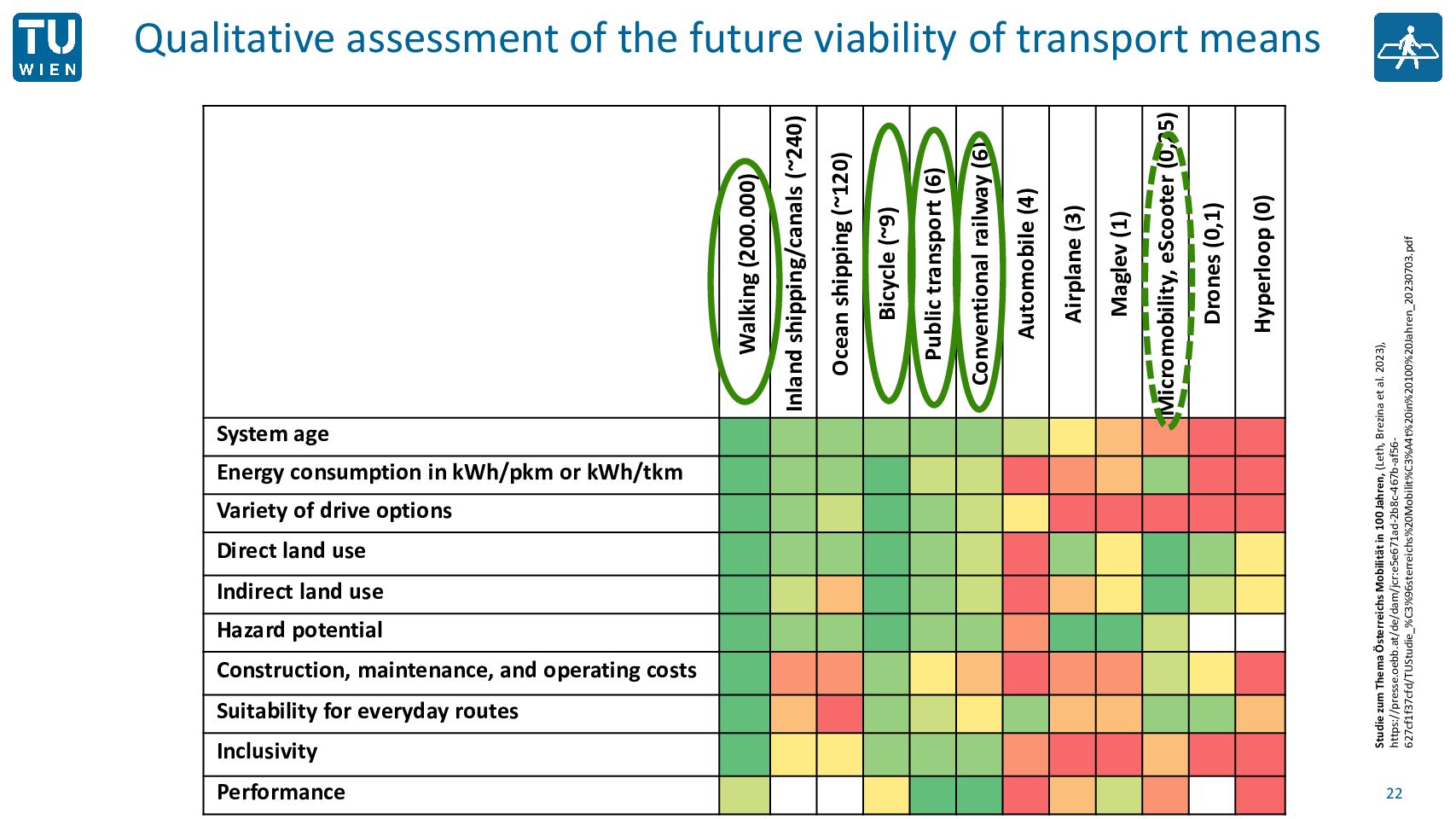

The Research Unit of Transport Planning and Traffic Engineering, at TU Wien has developed an indicator system to assess the sustainability of a transport mode from a systems point of view, based on the system in Vienna.

The results show the best options for the future of Vienna to be walking, cycling, rail, and public transport. “Specialised transport solutions like drones or the hyperloop may prove a niche for the wealthy, but they won’t provide global improvements from a sustainable mobility perspective,” comments Mr Emberger.

Systems approach, bigger picture, slow down

As cities like Vienna evolve with sustainability and zero emissions foremost in mind, approaches to transport and urban planning must evolve too. “When faced with congestion, transport planners typically increase capacity by building new roads. This approach has not solved transport problems over the last 30 years.” reckons Mr Emberger. Hence, he insists on the vital importance of teaching students to encourage a new generation of planners with a different mindset, i.e. a holistic approach to planning, research, and problem-solving. “We also need to train established transport planners, those taking decisions today, to rethink what they have done and likewise adopt this system thinking approach,” he adds.

Mr Emberger also advises caution over new technologies like e-mobility, e-commerce, social media, or AI. “They have unknown, long-term societal impacts. It takes between five to seven generations to really see these impacts.” The rise and fall of the car, which has existed for four generations, is a case in point. “The first 50 years were great. There was plenty of space. Then issues like congestion and urban sprawl became apparent.”

E-mobility, for instance, while offering a solution for reducing emissions, will not solve congestion or accident problems. Society has yet to fully understand its long-term impacts on raw material resources or microplastics pollution: electric cars weigh more than their combustion engine counterparts. The heavier the car, the more particles and microplastics wear off tyres and risk ending up in waterways.

“Urban and transport planning must take into account impacts at local, regional, national and international levels for the next three to four generations at least,” concludes Mr Emberger. “Instead of always wanting to develop faster and be more innovative, we need to slow down.”