💡 Accessibility of mobility

💡 Accessibility of mobility

Making travel easier for everyone depending on their specific mobility need means not only adapting physical access, but also digital access to mobility, as well as related services.

On 9 July 2021, Futura-Mobility organised a hybrid work session – in person and remote – with experts and members of the think tank.

Sylvain Denoncin, president of Okeenea, a company specialising in introducing support solutions for people with disabilities, points out the extent of the issue. “Over one billion people in the world today have a disability,” be it motor, sensory, or mental. So this directly concerns almost 15% of the global population, not counting all the others who might be temporarily limited in their mobility (pregnant women, seniors, children, people with physical problems…), laden (pushchairs, suitcases, shopping…), disorientated (unfamiliar city, tired…), or with specific needs like short people – including children – those with obesity or even with pathologies that involve specific needs (frequent access to toilets, for instance).

So accessibility of mobility is really about taking care of everyone; about creating an inclusive society where everyone can live together, each with their needs.

Anne Keisser, founder of Mon Copilote, points out how in her experience “with barriers to mobility, these people are going to find themselves isolated.” The service she set up in 2016 brings together a ‘pilot’ who needs to be accompanied and a ‘co-pilot’ who accompanies, via any transport mode: car, public transport, walking…

The many barriers to mobility are to be found across the whole travel chain: not knowing which bus to catch or how to react if a route is deviated, lacking sufficient strength to move one’s wheelchair, fear of taking the bus because it starts off so quickly there’s no time to sit down, not being able to buy one’s tickets…

Adds Anne Keisser: “in France, one out of four people who is elderly or disabled is socially isolated, and this despite a wide range of solutions that may already exist (carer, home help, taxis, carpooling, transport services for People with Reduced Mobility, public transport).” So, the need is very real and isn’t going to decrease because our population is ageing. Over 72% of the French population will be over 75 by 2060!

As for the accessibility of tourist travel, well this is another sensitive issue. “When asked, 80% of people with disabilities say if they don’t travel it’s because of issues with transport,” explains Marie-Odile Vincent, consultant for customers in wheelchairs for the tour operator Comptoir des Voyages. Air travel presents an extra barrier since passengers must part with their wheelchairs and trust the transport operator to ensure they arrive in time, and intact.

She continues, being in a wheelchair herself: “when I travel, I tend to say that 90% of my independence is lost and in this 90%, 100% of my mobility is lost!” Which leads her to remark that “the crux of the matter when we travel is mobility. Otherwise there’s no travel.”

From “transporting people with disabilities” to integrating everyone’s needs

Muriel Larrouy, head of transport accessibility, Ministerial delegation for accessibility, SG French Ministry for the Ecological Transition, thinks attitudes towards the accessibility of transport have greatly changed in recent times. “We have shifted from transporting people with disabilities to transport accessibility policies.” Furthermore, the word accessibility is relatively recent. It emerged in the 1990s and was brought to the fore by organisations and associations for people with disabilities. Prior to this, the accessibility of transport focused on transporting people with disabilities, on the medical aspect, but not the independence of those concerned.

The 2005 French law represented the institutionalisation of the accessibility obligation for the différents links in the travel chain: transport, the streets and public space, and the built environment (establishments open to the public/établissements recevant du public, ERP, and housing). Henceforth, all new services must be accessible (transport, ERP…) and major investments have rendered accessible many places and services that already exist. As this accessibility progresses in the field, use is developing and in its wake, questions over the quality of use and passenger information are becoming increasingly prevalent. This explains why the French mobility law (Loi d’Orientation des Mobilités, LOM), passed on 24 December 2019, includes several obligations aimed at facilitating use: specific pricing for travel companions, creation of an accessibility database to inform travellers about the accessibility of transport and the streets…

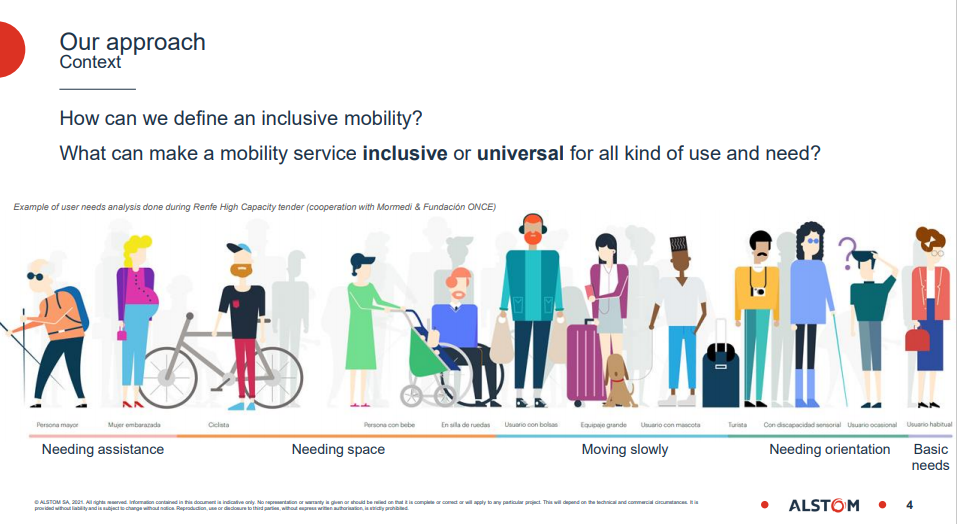

As for Alstom, Camille Jaigu, manager of metro platform programmes, explains the constructor’s approach: “We wanted to be as inclusive as possible in the way we talk about it. So we talk about needs: need for protection, need for information, need for space or need for time, rather than disabilities.” Thus Alstom has adopted the ‘universal design’ approach.

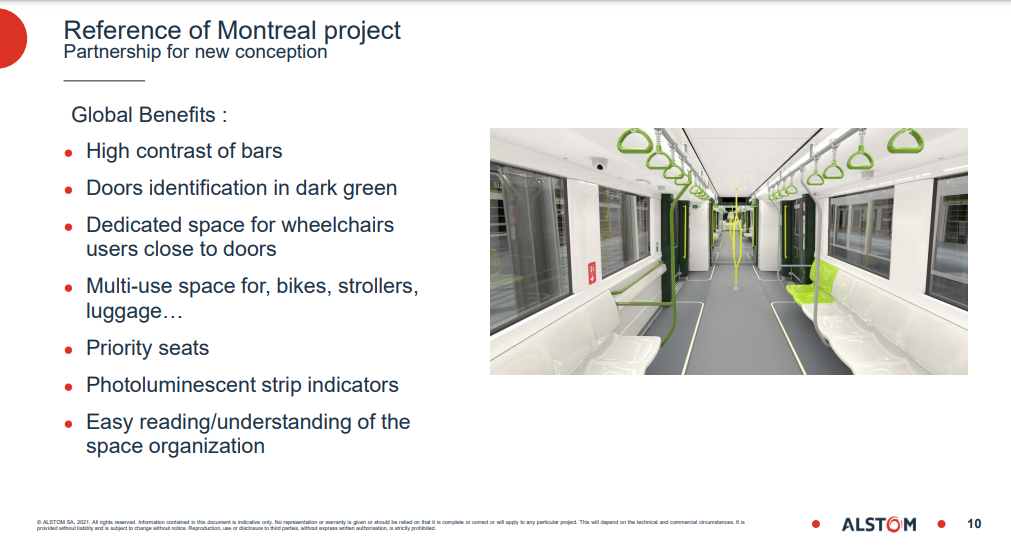

By way of example, Alstom is working on cognitive disabilities with Société des Transports de Montréal (STM) in Quebec, Canada. This involves reducing visual pollution generated by technical equipment by streamlining the train design as much as possible, while highlighting wayfinding elements useful to passengers: light strips for boarding and alighting, constrating colours for support bars, etc.

Technical support certainly, but services with the human touch too

Should everyone be able to access transport fully independently? Obviously, but what is independence? What does it depend on?

Enabling everyone to make trips without human assistance and only with technology-based support, fully independently, isn’t a stated objective in other countries. “Herein lies a specifically French debate!” points out Muriel Larroy from the Ministry. “France is a nation of engineers who expect machines to meet needs.” Indeed, in countries like England or Germany, “the thinking is that individuals have greater value and that human intervention can be far more qualitative” … and then, sometimes, machines can fail.

Anne Keisser, founder of Mon Copilote, explains how she “makes use of technology to have the human.” She has adapted services provided for the specific needs of the public in question right from the design phase of her offer. The founder explains, for instance, the importance of proposing both a call centre number and a website for bookings, “because this fragile public may struggle with the internet and above all needs human contact.” Likewise payment options include sending cheques, since some people may be uncomfortable with remote payment by bank card. “It’s important to build confidence with this community, since they are fragile individuals,” she insists.

Today, Mon Copilote is active in France through partnerships with mobility organising authorities (autorités organisatrices de la mobilité, AOM) and/or transport operators across four territories – Clermond Ferrand, Pau, Sénart and Essonne – and soon in Paris. The service has 4,000 users in the Hexagon and supervises between 200 to 300 trips daily.

Marie-Odile Vincent, travel organiser for wheelchair-user clients, believes it is possible to reconcile disability and travel by taking into account the cultures of different countries, and the service culture in particular. “System D works collectively when you know how to clearly explain what you need or what your difficulties are,” she explains.

Transport operators must pull off a balancing act between developing technology-based services to facilitate autonomy and introducing human assistance that is satisfactory for passengers, as well as from a business model perspective. “With government and the Regions we are constantly trying to find the best business model in terms of staff presence. It’s a balance between what we can do technically to render people as independent as possible and what we can do in terms of human support,” explains Laëtitia Monrond, accessibility director, Groupe SNCF.

Inclusive thinking also when designing services

The industry groups participating in this Futura-Mobility session have all adopted an inclusivity approach for the public in question when designing, testing and adjusting their services.

This is the case for SNCF, which liaises on a permanent basis with nine associations for people with disabilities to improve train transport accessibility, covering all rail operators; for Keolis through testing wayfinding for people with impaired vision at Versailles Chantiers; for Alstom in Montreal with the associations Ex-Aequo and RUTA Montreal, plus the association ONCE in Europe; for Aximum (Colas/Bouygues) by introducing tactile strips to make it easier for visually impaired pedestrians to negotiate risky road crossings.

Making information on accessibility available

For foreign tourists with disabilities who wish to travel in France, according to Marie-Odile Vincent, “the first issue is accessing information: finding the services available to me that are limited and often have to be reserved a long time in advance.”

Whether for locals or tourists, since the 11 February 2005 law came into force, France has really stepped up its efforts terms of facilities, information, and quality of use. The latter depends on a specific need: having reliable information on accessibility at one’s disposal to prepare a trip, from start to finish, even though facilities are not adapted everywhere.

The French law of 11 February 2005 on equal opportunities requires that all public transport operators ensure their networks are fully accessible by 2015. Covering the whole travel chain, this accessibility concerns transport modes and, across the board, all their contexts: built environment, public space, roads. The law aims to make people with disabilities as ‘independent as possible.’

In December 2019, the French mobility law (Loi d’Orientation des Mobilités, LOM) focused on data, including on information accessibility. It recalled the obligations already existing in the 2005 law and put forward two measures on information accessibility:

- Obligation to introduce a single booking platform for assistance services in stations.

- Creation of databases describing the accessibility of streets and transport, on condition accessibility is brought to the fore in the same terms and the information organised in the same way. For transport, the model to be used is NeTEx – NeTEx France profile – July 2021. Street data must be inputted in a compatible format. Both decrees were published at the end of June 2021.

In the business world, digital wayfinding services for people with disabilities are now emerging.

NaviLens, for instance, is a digital wayfinding service for blind and visually impaired people in public transport. This solution is based on a 2D QR code, in colour, adapted and augmented, positioned along the route, that can be read up to almost 50 metres away and from wide angles. The user turns on their phone, hangs it around their neck if necessary, and the app then automatically detects the QR codes along the way and guides the user with audio.

With Keolis, trials were recently carried out at Versailles Chantier station, a multimodal station with complex pathways.

In the words of Arnaud Julien, innovation, data & digital director, Keolis, “this solution is mature so we are really more testing the use cases than the technology itself.” The app guides users quite clearly, especially with regards which direction to read the QR codes, and in return delivers voice messages, either dynamic and in real time, about the number of steps to take, for instance (see photo), or static, about, for instance, the times of the next buses.

Even if users need time to adapt to this solution, which itself depends on infrastructure flow (presence of tactile strips), it proved extremely popular among the test bench of visually impaired people, who would like to see it become more widely available. Next step in this direction, the company NaviLens is working with Alstom to equip train cars.

Another version of the NaviLens app using the same 2D codes has been developed for travellers who don’t know the stations or or speak the local language – clearly of interest in Versailles!

Okeenea is also developing a guidance app called Evelity. The aim is for it to work everywhere, including inside buildings. It functions indoors via Bluetooth beacons that localise the user’s smartphone by triangulation, like GPS. What makes this app special is that it addresses all types of disability, adapting to specific needs, customised by the user (stairs, lift, for instance…). There is a dedicated back office for operators who can, for instance, close travel routes.

Sylvain Denoncin, president, Okeenea, reckons “we need to create a personal mobility assistant whose key success factor is its ability to adapt to the needs of users.”

Guiding the user is based on voice, which is well suited to people with impaired vision but also, for instance, people in wheelchairs, who need to use both hands. The system means you can keep your phone in your pocket.

Deployed in Marseille’s metro system, in a tertiary sector tower block in Lyon, currently being rolled out or tested in Paris for the tram 3a-3b changeover, in Lille, Lyon or even New York, the app is constantly evolving.

So this development, following on from the LOM, is providing data both standardised and up to date, which is vital. “It now remains to offer users services that are as interoperable as possible, focused on use and not technology, and which enable real mobility across the whole travel chain including transport, the streets, and establishments open to the public,” insists Sylvain Denoncin.

“Facilities, information for use, and the human element: there must be synergy between these building blocks” to improve the accessibility of transport for all, sums up Muriel Larrouy.

Translated into English by Lesley Brown