💡 MaaS / Part 1 – governance and influence on mobility

💡 MaaS / Part 1 – governance and influence on mobility

by Joëlle Touré, delegate general, Futura-Mobility

On 9 & 10 March 2021, Futura-Mobility organised a session over two mornings dedicated to Mobility as a Service (MaaS).

After kicking off to great fanfare in 2015-2018, together with big promises and a great many expectations, MaaS is today facing reality. So now the time is ripe to take stock of the concept and explore some key questions: what governance should be put in place for a successful MaaS project? How can MaaS projects address the challenges of sustainable mobility?

With MaaS, who does what?

Maxime Audouin, research author on the topic of governance when introducing MaaS systems in Europe, Helsinki and Vienna in particular, opened the session to discuss scale when deploying MaaS. “The right scale is metropolitan even regional. Indeed, in urban centres the mobility offer is good and structured. The crucial question is: how, as you move further out of this urban nucleus, to propose an offer combining all the different mobility solutions that can compete with the service level of private cars?”

Empower or Thwart? Insights from Vienna and Helsinki regarding the role of public authorities in the development of MaaS schemes, by Maxime Audouin & Matthias Finger

Yet says Laura Papet, associate director at French consultancy PMP Conseil, “ultimately, there are few echelons and few local authorities with a line of expertise on the scale of the catchment area. So when you start talking about MaaS and territorial MaaS, the first question that necessarily arises concerns interaction and good governance, if only in strategic thinking, between different institutional echelons.”

Nonetheless, everyone agrees that Public Transport Authorities (PTA) have a role to play in the advent of MaaS services.

According to Olivier Vacheret, department head, Information & Digital Services, Ile-de-France Mobilités (IdFM), “in France, the LOM [2019 mobility orientation law] makes room for PTAs and this is pretty good news, especially given the opportunity of disseminating open data with a controlled level of quality (…), meaning all the applications can ultimately promote public transport and sustainable mobility.”

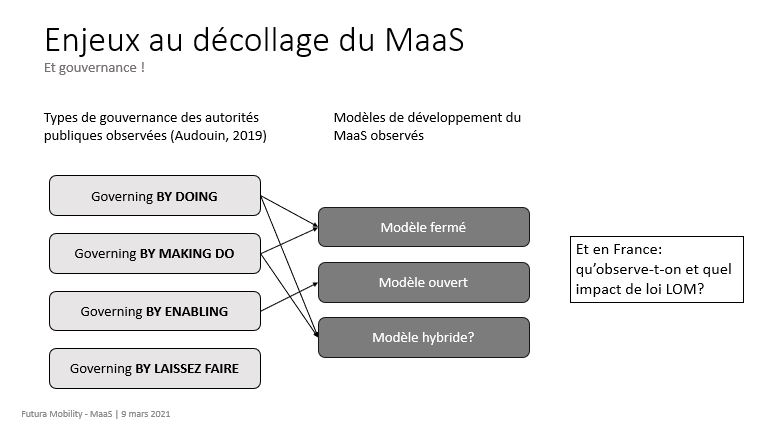

During his research at EPFL (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Lausanne), Maxime Audouin observed four approaches to MaaS adopted by authorities, illustrated below. “When talking about public authorities we are especially talking about the PTA, but also regional scale and governments,” he clarifies.

- In the governing by doing approach, the PTA takes sole control of introducing a MaaS service, with development carried out internally. Such is the case, for instance, for the PTA (Wiener Linien) in Vienna, which has created a dedicated in-house entity to develop its MaaS solution.

- Governing by making do is fairly close to the above approach, except the PTA, which retains overall control, contracts development out to an external service provider. “This is the case in Berlin with BVG, which opted to entrust development of its MaaS service to Trafi,” illustrates Mr Audouin.

Laurent Chevereau, MaaS project director, CEREMA (French Centre for Studies and Expertise on Risks, the Environment, Mobility and Urban Planning) points out how this is also the approach adopted by local French authorities, through public service delegation agreements, “as Saint-Etienne and Mulhouse have done, for example,” or through a specific market “like in Rouen, Grenoble and Marseille.” One may wonder which of the two models will prove the most popular.

Ile-de-France Mobilités in fact uses both approaches. It’s a question of ‘make or buy.’ The PTA would like to open up governance so as not to be the only one steering MaaS, but “it’s not simple, there needs to be legal forms, good practice,” explains Olivier Vacheret from IdFM.

- In the governing by enabling approach, the public entity lets many stakeholders offer a MaaS service on its territory, encouraging ‘in the market’ competition. Transport for London (TfL), for instance, has long pioneered this position by accepting to open up its data and allowing MaaS actors, like Citymapper, to resell its tickets. “Many central governments have also adopted the same position. I’m thinking here of Finland’s government with its Finnish Transport Code, which seeks to overcome barriers to MaaS services, or the French government with the LOM,” explains Maxime Audouin.

- A final approach observed, whereby “you could say the PTA procrastinates,” is ‘wait-and-see’ governing. For instance, this has long been the position of Helsinki’s PTA, which refused to open up its transport tickets for reselling by third parties. “National regulations often come and shake up this approach, as was the case in Finland.”

With regards these four approaches, different development models for MaaS may emerge (see diagram above): a closed model with a single MaaS service on a given territory, an open model with several MaaS services competing, or hybrid models like, for instance, “a PTA steering development of a digital infrastructure (shared back-end) that several MaaS user services/interfaces plug into.”

The latter is in fact the model adopted by Ile-de-France Mobilités (IdFM). Olivier Vacheret from IdFM explains further: “knowledge of customers and usage is better managed if the PTA itself produces a number of MaaS building bricks – to stay in direct contact with usage and consequently steer public mobility policies.” For instance, subsidies allocated by IdFM for car-pooling trips have been notably exchanged for usage data, which means offers can be adjusted if necessary.

But might there be a model more supportive of developing MaaS to better tackle mobility issues?

Maxime Audouin reckons “with a fully deregulated approach comes the fear of a negative impact on the performance of a transport system serving a territory. (…) The pure players who are going to offer a MaaS service are seeking financial profit, which will be more easily gained by selling semi-private services (taxi, ride-hailing) rather than public transport tickets, often heavily subsidised.”

For Hans Arby, founder of Ubigo and now vice-president of Gothenburg’s PTA, “in a good MaaS system, everyone plays to their strengths. In my view, commercial actors are very good at meeting customers’ needs and aspirations, while public authorities are best placed to govern, i.e. framing and enabling implementation.”

Towards transforming mobility habits?

According to Laurent Chevereau from CEREMA, introducing a MaaS service potentially addresses many issues, yet what’s important for a PTA is “choosing!” the desired outcomes and target groups: tourists? Locals? Families? Professionals?

Moreover, David Lainé, director France, Belgium and Southern Europe, Trafi, believes for MaaS to prove a success, “you need a bold mobility policy that encourages people to change their travel behaviour, the aim being to reduce use of private cars.”

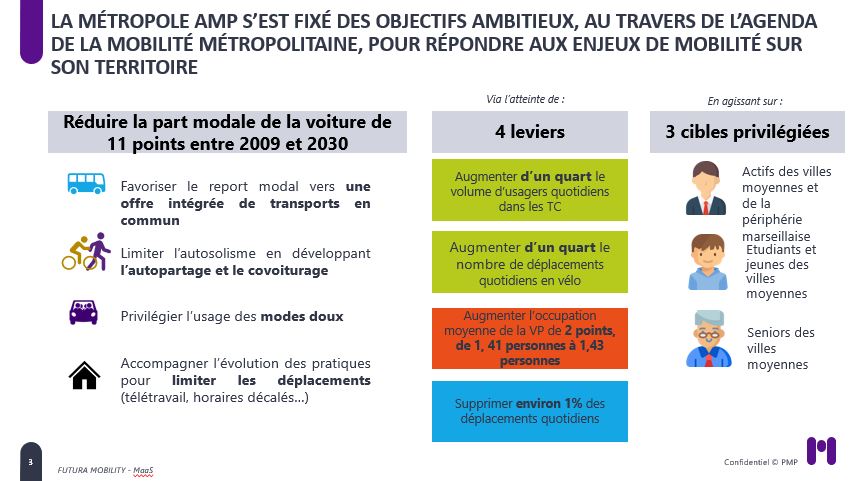

At Aix-Marseille Provence Métropole (French administrative entity) “the idea, prior to any reflection on MaaS, was to rethink a mobility marketing strategy at territory scale,” explains Ms Papet. Doing this requires knowledge of the mobility needs and habits across this territory, especially of people using private cars. Next, a strategy can be introduced as well as a marketing action plan, followed by an overhaul of the transport offer and pricing.

Using this insight, the offers and services to be integrated into the MaaS service can be prioritised depending on the issues faced. For instance, to tackle single car use, “in Grenoble we started adding off-street parking and mature car-sharing offers to the Pass Mobilité travelcard, as well as developing a dedicated traffic lane for car-sharing between Voiron and Grenoble,” expands Laura Papet from PMP Conseil.

For Julie Sulli, head of transversal marketing projects, Keolis, “the challenge is very much about putting private cars in their proper place and integrating them into this global mobility offering in the catchment area.” Keolis, whose natural customers are public transport users, is indeed eyeing wider targets over the long term, especially people in the suburbs whose mobility is key to meeting sustainable mobility challenges.

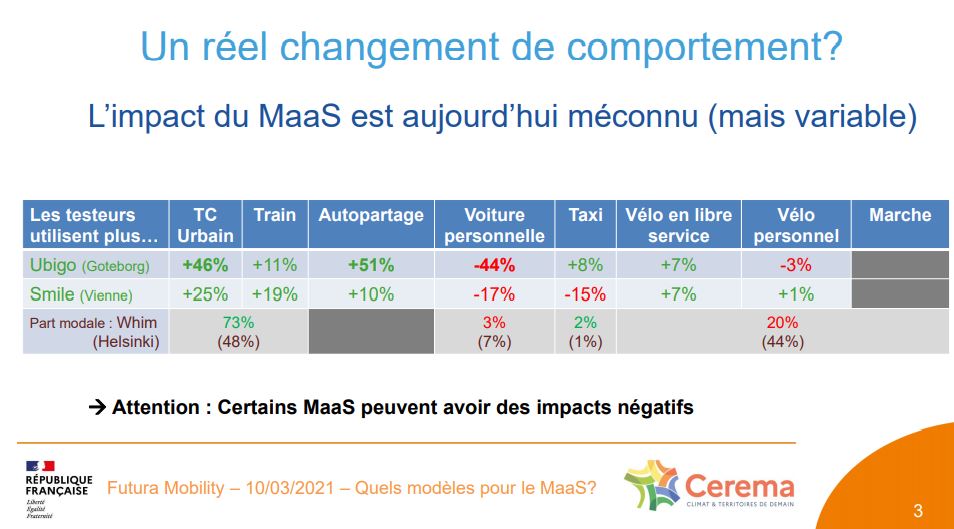

Once MaaS is up and running, “to what extent have service users managed to make a modal shift? There’s little data, yet plenty said in studies,” remarks Mr Audouin. Nevertheless, Laurent Chevereau from CEREMA presents some results that do show there has been – if user feedback is to be believed – a virtuous modal shift for UbiGo in Gothenburg and Smile in Vienna.

Conversely, some transport modes that are part of MaaS, like ride-hailing, appear to be having a negative effect on transport issues city-wide. “A study by MIT on the impacts of Uber and Lyft shows these services increase the intensity and duration of road congestion,” points out Maxime Audouin. Mr Vacheret from IdFM also adds how “the study reveals the ride-hailing customers questioned don’t wish to use public transport and moreover own cars. This study shows that using ride-hailing doesn’t demotorise households!”

Impacts of transportation network companies on urban mobility, by Mi Diao and Jinhua Zhao

At IdFM, for intermodal trip offers, “we are aware of sometimes less than welcome impacts. For instance, electric scooters are gaining modal share from walking. (…) From a public health perspective, this raises questions…. Sometimes the e-scooter gains modal share from metro systems, too. As was the case for Autolib’ [Paris, city-managed, electric car-sharing service, in service from 2011-2018],” explains Mr Vacheret.

For Mr Chevereau from CEREMA, clearly “there is a lack of data assessing the impacts of MaaS. Everyone is aware of this shortfall and there are an increasing number of projects, particularly European, that plan to provide answers to questions over MaaS, such as the impacts on modal share, on volumes of journeys and distances travelled.”

MaaS and Covid19: more ‘chosen mobility’ post-pandemic?

Three key changes have been observed during the health crisis: more digitising of mobility services, an uptick in the use of micromobility devices (see The role of mobility in micromobility), and a significant downturn in passengers on core transport networks in cities “of around 60 to 70%,” reckons Maxime Audouin. Observations that lead him to say “MaaS is an opportunity for public transport to recover post-Covid, to get people back onto public transport and even attract other riders like single-car users.”

Julie Sulli from Keolis raises the question: “ultimately, are we not shifting towards more chosen mobility? As such, the MaaS service could be an impetus for greater choice.” In Vélizy (Paris suburb), Keolis is, for instance, running a trial whereby passengers can select their travel route depending on the occupation levels of buses.

From here to imagine MaaS one day imposing its journey routes to manage passenger flow in ever-growing megacities… is just one step away…

Cover photo: Gerd Altmann – Pixabay