Hans Arby: MaaS – March 2021

Hans Arby: MaaS – March 2021

Founder of the pioneering MaaS (Mobility as a Service) platform UbiGo, over the past 15 years Hans Arby has also provided support to cities in developing transport strategies, long term planning, and marketing public transport. He currently runs a consulting business and is a member of the Combined Mobility Commission at UITP, where he is also lead trainer for MaaS. In January 2021 he was appointed 1st vice-chair of the Transport Board at City of Gothenburg.

A speaker at Futura-Mobility’s open session on MaaS, in March 2021, Mr Arby explored the concept from his hands-on experience in both the private and public sectors.

Futura-Mobility: What is MaaS seeking to achieve?

Hans Arby: MaaS is an extremely broad concept and there are diverse interpretations. For me, it’s really about transforming the mobility ecosystem to offer users in a city easy access to the most suitable mobility options. This also means challenging the [car] ownership model. We can do this in many different ways with many different actors. But it’s complicated.

F-M: From conception to commercial roll-out and everyday operations, why is MaaS complicated?

Hans Arby: For various reasons. Mobility always depends on the local context. You have to find ways of cooperating with public and private actors. Also, many people tend to forget that for mobility you always need an asset, some hardware to transport people – it’s not just about digital. Then the market is extremely conservative and siloed. Most actors want to keep their customers for themselves rather than share them; furthermore, since the margins are low, they don’t want to take any risks but prefer ‘business as usual’. Mobility isn’t not standardised, either. Sometimes people say MaaS is ‘Netflix for mobility’, which of course isn’t true because Netflix is a pure digital, standardised and global service, which mobility is absolutely not.

“For me, MaaS is really about transforming the mobility ecosystem to offer users in a city easy access to the most suitable mobility options. This also means challenging the [car]ownership model. We can do this in many different ways with many different actors. But it’s complicated.”

F-M: Are the private and public perspectives on MaaS compatible?

Hans Arby: Public city authorities focus on residents. When it comes to mobility, they want an accessible and sustainable city for all. From a private viewpoint like UbiGo’s, for instance, which is customer-centric, the mission is to offer easier everyday travel. So yes, both actors are working with the same target group, the same people in mind, but different goals. But, with good governance the end result will be the same.

F-M: Could you dig deeper into the various MaaS structures and levels of integration?

Hans Arby: There are different types and dimensions to structuring MaaS. You could say it comes in various ‘flavours.’ One is ‘A-to-B MaaS’, which sort of solves the single, intermodal trip, the first/last mile, a single ticket maybe. Another ‘flavour’ is more about ‘morning to evening MaaS’, trying to meet all the mobility needs across all the transport modes. This second one is very much targeting car ownership because solving every individual trip simply isn’t enough. MaaS needs to solve all trips if it is to convince people to sell their car and consume mobility services.

Based more on customer and business model viewpoints than technology, there are various levels of integration. First there’s integrating information, like in Google Maps, which guarantees the information provided is accurate. Here you can make money on ads like Google does.

Then there’s integration of single trips, booking and payment, where you guarantee payment and delivery of the right tickets – as is the case with Jelbi in Berlin. Here revenue is based on commission.

The third is integrating the complete service offer, mostly subscription based, and is more about taking responsibility for the quality of the services. It involves repackaging, like an all-inclusive charter trip but for everyday mobility.

Finally, you have governmental and city authorities, who will want to be sure the MaaS service integrates societal goals at each of these three levels. They will want to make certain the mobility options in the city are attractive and sustainable, also that contracts with resellers are designed to deliver the right outcomes.

F-M: Could you tell us more about UbiGo’s activities in Gothenburg and Stockholm? Especially its household-based subscription offer, which is quite unique.

Hans Arby: Gothenburg, Sweden’s second largest city, currently has a population just over half a million and growing. It’s centred around the harbour and is home to Volvo and many other automobile companies, MedTech West university and so forth. The city model is similar to that of a US plant city like Detroit, i.e. accessible by car with loads of big roads. Yet it is currently trying to shift towards offering accessibility by public transport, bikes and proximity – to make the city denser and services easier to reach.

UbiGo piloted in Gothenburg between 2013 and 2014. We then launched commercially in Stockholm in 2019 offering public transport, bike, car sharing, rental car, taxi, etc. based on a flexible subscription for households. This is what UbiGo calls a MaaS level 3, fully integrated service.

Why the household subscription model? Because we realised the car represents a common resource for the whole household, so to replace it you have to meet all the travel needs of the whole household. This is what our subscriptions seek to achieve – morning to evening, Monday to Sunday, January to December. The aim is to reduce the need for a car so much that households won’t want to buy one anymore. However, to be honest, targeting car ownership and starting selling to car owners isn’t easy! It takes a long time because we’re talking about making a big change in established behaviour.

Interesting though, how the number of UbiGo customers increased during the Covid-19 pandemic in Stockholm, especially around weekend car hire.

F-M: UbiGo is closing down in 2021. Does this mean the B2C (Business to Customer) concept is dead?

Hans Arby: If you look at cities, how many are there where you can be a commercial MaaS operator? There’s only a handful where you really can resell and integrate public transport. Plus, don’t forget it’s still very early days. Another point to remember, all the different models have 2C at the end. If you focus on the B2G [Business to Government] market, the public transport operator or city then must be able to attract customers – you still need an attractive offer otherwise what’s the point of running the service at all? The same applies to B2B [Business to Business] – the services must appeal to employees.

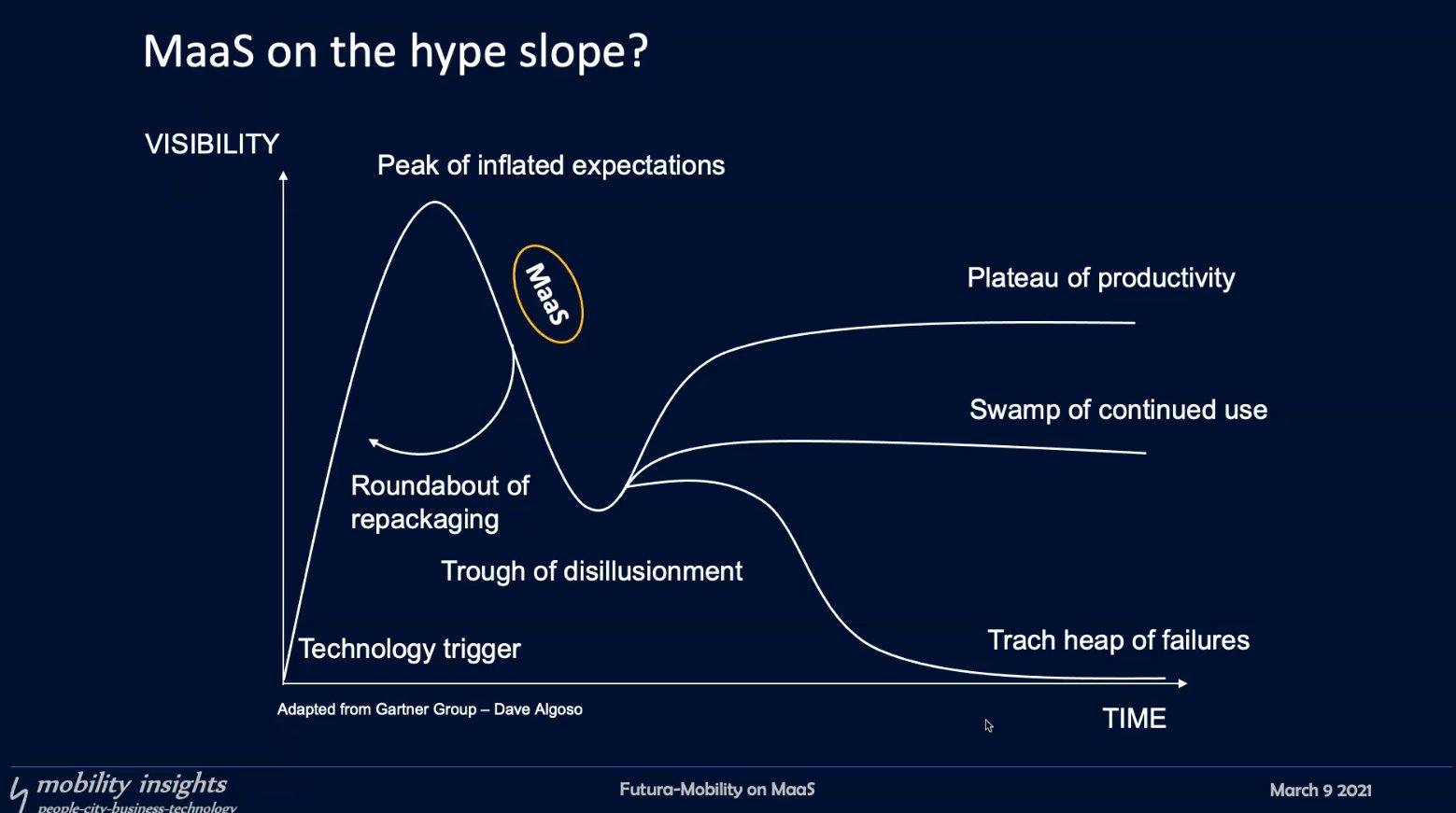

There are few other examples of commercial services like UbiGo. Most are still in the pilot phase. We are still learning. With regards the Gartner hype curve below, right now I think MaaS is on the downwards curve, but it will be interesting to see where it reaches the productivity plateau. I like this version [below] a bit more than the standard Gartner Group curve because of its ‘roundabout of repackaging loop’, which suggests MaaS will probably be repackaged by new actors several times before we understand it has to be productive.

“Right now I think MaaS is on the downwards curve, but it will be interesting to see where it reaches the productivity plateau. […] The ‘roundabout of repackaging loop’ suggests MaaS will probably be repackaged by new actors several times before we understand it has to be productive.”

F-M: Who should do what in a MaaS model?

Hans Arby: Well, in one you have a commercial actor doing the business and technical integration themselves, as well as creating the offer and competing for tenders. Sometimes this approach is called the liberal model; Sweden and Finland are good examples. Of course, the challenge here with the business model is to be profitable.

The third model is where public transport expands its offer, as is the case with Jelbi in Berlin and in other German cities like Hannover, Hamburg, and Munich.

Then there’s the middleground, a typical Swedish compromise, where the city or PTA sets up a platform for use by both transport service providers and open to any player, transport or digital, wishing to build apps to sell to customers. This is what we are seeing with the LOM [mobility orientation law] in France, as I understand.

In France, the LOM (mobility orientation law) legislation of 24 December 2019 unlocks data collected from transport and mobility services: henceforth PTAs must make it openly available, for free. This opening up is part of a drive to develop digital mobility services nationwide.

All the above models present challenges, from a PTA point of view. One is the need to create value for the service providers to encourage them to be part of the service, regardless of who is running the show. Also, you must have good services to integrate, which depends on cooperation between the different actors. Indeed, this cooperation is really the key to everything: PTAs must first establish this cooperation, then focus on building a technical platform to deliver MaaS. Remember, MaaS is not at all about technology.

F-M: Any pointers on how to build a successful MaaS ecosystem?

Hans Arby: If the ecosystem is to prove a success, each party should play to their strengths. In my view, commercial actors are very good at meeting customers’ needs and aspirations, while public authorities are best placed to govern, i.e. framing and enabling MaaS.

Take UbiGo’s deal with SL, Stockholm’s PTA, for instance. As a commercial actor, we promised to reach customers the authority can’t reach itself, to be revenue neutral, and practice fair pricing compared to what SL offers its direct customers – even though we had a completely different pricing model.

On the framing side of MaaS, public authorities should focus on aspects like procurements and contracts.They should also work on disincentives like parking policies and congestion charging – making it less easy to use private cars – so all the MaaS mobility offers can thrive.

When it comes to enabling MaaS, there are many tasks for the authorities, too. Such as offering parking space for shared services and creating mobility hubs, using public procurement to get different services off the ground, or running innovation programmes and pilots.

F-M: Your advice to public authorities going forward?

Hans Arby: As part of an open network, an ecosystem like MaaS, public authorities are sometimes buyers, sometimes sellers. In this context it’s important they understand their negotiating power – what assets are you sitting on? What can you offer? What deals can you have with resellers?

They should also bear in mind that MaaS needs many different initiatives – so don’t close the doors!

Furthermore, when introducing a public platform, less can be more. This is because a public platform could be everything – from standards to a common data lake for sharing data, all the way up to full integration with payment and contracts. In this case, there’s a risk of freezing development since the platform will never be able to evolve as fast as it needs to because it will always remain in the early phase.

Going forward, I would encourage PTAs is to do as many lean start-ups as possible, i.e. start with the minimum viable product, build and learn from it to eventually set up an IT platform, then see what happens. Also, stay open to taking on different roles. I believe Public Private Partnerships are about everyone doing what they are best at.

At the same time, don’t forget that every city, every country is different. When it comes to MaaS you can’t do a copy and paste!

“MaaS can never replace efficient and attractive public transport, good cycling and walking infrastructure.”

A final reminder especially for public actors: MaaS is always the grease you put on top of all the other things you are doing right. Sometimes, especially from the US, you hear things like: “well, we don’t need to invest in public transport. We can do MaaS instead.” But it doesn’t really work that way. MaaS can never replace efficient and attractive public transport, good cycling and walking infrastructure.