💡 Mobility in the US – context, trends & future

💡 Mobility in the US – context, trends & future

20 September 2019: during this Futura-Mobility session, live streamed from California to Paris, speakers from Valeo US and Winnovation, a Bouygues subsidiary, set the current mobility scene in the US, unpacked the trends, and explored future scenarios…

Part 1: Setting the scene

Out of the roughly 350 million people in the US today, half live in just nine of the country’s 50 states – “and we expect to see around the same concentration come 2050 with a population of some 400 million,” reckons Peter Groth, manager, Valeo Mobility Tech Center, Valeo Driving Assistance Research US.

In terms of living area type, there are four main categories: urban; suburban – “a trend that continues to grow”; rural; and ‘exurb’, an emerging term that describes when housing gets build in a rural area beyond the limits of existing cities and their suburbs, so they represent unincorporated ‘townships’.

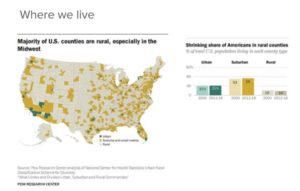

Another point of interest, every state is divided into a certain number of counties that tend to get larger as you go west. A study by the Pew Research Center found that in these counties, 50% of the population lives in suburban settings, the lowest percentage – 16 to 14% – in rural areas, then the remainder of about 30% in urban county areas, “which to a certain percentage are suburban,” pointed out Mr Groth.

People are continuing to spread out. They are moving to the suburbs more than to urban quarters – “a trend fundamental to understanding the US,” said Mr Groth. “Furthermore, yes I would say we have a road trip culture. Why? Because it’s cheap to drive, you see a lot of nice things. This culture, that in the US people don’t shy away from getting in the car to go places, is one reason why we have a lot of cars.”

The car versus public transport

The car is still king in the States. Data from the Transportation Energy Data Book N°36 shows around 20% of households have three or more cars; 30% have two; 30% have one; and a little under 10% don’t have one at all – “which I find strange,” commented Mr Groth.

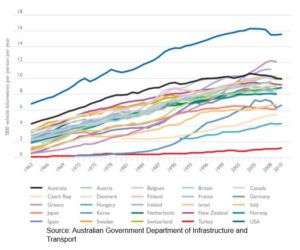

In terms of the number of kilometres by car/per person/per year, the graph below shows the US is driving a lot more than other countries. “I think this is explained simply by the developing suburbs, people living away from city centres, the fact we are commuting to work quite a bit, that we’re not scared to take road trips, and that people continue to spread out,” commented Mr Groth.

Another interesting way to view these behaviour patterns, a study by the US Energy Information Administration looked at passenger miles per country by mode for 2012. Key findings show that Canada does even more by car than the US. Also for these two countries, passenger rail use is very low and bus use low.

In the US, it is still much easier to jump into a car than use public transport. “Indeed, public transit ridership numbers are under 10% in most US cities, except in New York where they are 20% – but this is an exception and doesn’t represent America,” pointed out Mr Groth. “All in all, ridership numbers are down, so it’s not developing well.”

A further insight is the connection Americans have with their cars. Full-sized pick-up trucks were the top three selling vehicles in 2018.

“There’s a certain percent of the population using pick-ups and SUVs instead of cars because they are practical for recreation, i.e. carrying equipment, towing trailers with motorbikes, for travelling between states, plus gas is cheap and we have the roads,” said Mr Groth. “So these types of vehicle are very much part of the American identity – an important point to bear in mind when thinking about autonomous vehicles and trends into the future.” In other words, will Americans want to give up car ownership and driving?

Who does what?

The nature of the legislative framework in the US makes changes to transport infrastructure and standardisation longer to implement. Three levels of government – federal, state, and local – are responsible for different elements of the transport ecosystem. Having to deal with different authorities, depending on what you are working on in the transport field, is creating confusion. It is slowing the progress of some aspects of AVs. For instance, when it comes to licencing, or safety, or certification, or the equipment allowed on the vehicles, who is in charge of what? The situation is much simpler for air transport and aerial mobility, which falls completely under the federal government.

Furthermore, new mobility may take longer to happen because ownership and management of transport infrastructure is spread between different types of entities, like federal, state, county, town, etc. “So when you’re trying to implement something involving infrastructure, you’re dealing with a lot of different people,” pointed out Mr Groth. “For example, road signage is mandated at state level, which means it differs from state to state.”

Part 2: Mobility trends & developments – investments count

David Hermina, innovation and collaborative research manager, Valeo, then presented mobility trends in North America based on analysis of investments – an approach that came as a surprise to our European minds, being more accustomed to studying them through the prism of pilots, user figures, and feedback from the field.

We learned that the AV segment is attracting the lion’s share, a total of US$11.41 billion, almost $2 billion annually, between 2014-2019. Followed by $29.7b ($1.75b/year) invested in shared mobility since 2002; $1.73b ($0.22b/year) in last-mile solutions since 2011; $1.33b ($0.17b/year) in micro-mobility since 2013; and $45 million in aerial mobility since 2015. Important to note, however, is that for aerial mobility – “we are missing data from Google, Amazon, and Tesla, all major players,” said Mr Hermina.

“The segments are clearly at different levels of maturity. While aerial mobility is off the radar, markets such as electric scooters are in consolidation,” he added.

Recent developments include new AV alliances coming to market like Volkswagen’s partnership with Ford to invest in Argo AI, a start-up working on developing autonomous cars. In shared mobility, Uber is trying to change the business model with an all-in-one subscription offer. Last-mile mobility is seeing alliances with B-to-C players, like between Walmart and the robot delivery start-up Uldev.

“The common link between all these mobility segments, such as AVs and micromobility, is electrification,” added Mr Hermina. “Bearing this in mind, tomorrow’s infrastructure must be able to power all of them.”

Part 3: mobility 2050

Looking into the crystal ball, the panel then tried to predict to a certain degree the future – what mobility 2050 will look like three decades from now – by examining 1) the challenges to get there and 2), hypothetically, the consequences for people and society three decades from now.

- Shared mobility

Mr Hermina insisted on the need for consensus on what ‘shared mobility’ exactly means. Some definitions include scooter micromobility, others courier networks like on-demand delivery of food, and so forth. “Right now, it’s unclear and this lack of consistency is hindering best practices to be shared, tailored, and deployed.”

Another must, he reckons, is guaranteeing shared mobility coverage across areas and integrating it with public transport to reduce spatial segregation. This is because silos are starting to appear, with different types of mobility mediums for different types of distances being offered in different regions.

Shared mobility in 2050 may well give rise to new models for both users and providers, like, for instance, vehicles being used according to the type of journey. Insurance too, traditionally based on vehicles/assets, may well evolve into a mileage model instead. In the future, companies might be obliged to offer their employees subscription packages for multimodal mobility as part of their work contracts.

- Last-mile mobility

How to bridge the last-mile to last-metre gap if robotic devices or drones take off? From an infrastructure perspective, there is the question of accommodating all these types of mobility – will there be dedicated lanes, a need for inclusive design to ensure vehicles and buildings can accommodate this last mile?

- Micro-mobility

Challenges come 2050 might centre around regulations, storage, and scale. “One consequence of roll-out could be a lack of traditional car mechanics as expertise shifts to servicing electric scooters and other micro-mobility devices,” suggested Hédi Calabrese, construction and road tech analyst, Winnovation.

- Aerial mobility

Anticipated challenges for this segment may include obtaining permission to operate and the division of airspace. A question mark also hangs over the emergence of a business model that can ensure enough capacity to make the transport mode attractive pricewise for users.

“Potential consequences could be rising insurance costs for buildings and the creation of ‘fly zones’,” said Mr Calabrese. “There we might see drops in property values and higher insurance premiums for buildings lying in such zones, plus the need to review construction methods, e.g. structural strength of buildings, and the future of rooftops – if used for aerial mobility, there will no longer be room for TV and phone masts, air conditioning units and other such equipment.”

- Autonomous vehicles

“We rate AVs very difficult to do,” said Mr Groth, concentrating on two challenges “that worry me the most with autonomous driving”.

Firstly, to be useful, it needs to be offered in enough places to make money. This means being able to drive pretty much everywhere, all the time, at Level 5 (fully autonomous). But to do this the vehicle technology has to master edge cases – like bad weather conditions or negotiating road traffic stopping and starting unexpectedly – and have sufficient perception to understand scenes perfectly. According to Mr Groth, this perception remains quite limited and even simple scenarios that happen every day in every city are extremely hard for AVs to deal with. “So the road will be very long in terms of mastering all of these different situations.

“A lot of the AVs deployments today in the US are done in areas where it’s easier to drive, like Arizona or suburbia where the speed limits are low, the roads large. If there’s a problem, the vehicle can simply stop,” he added. “If you’re doing a viable service and the vehicle is constantly stopping, the customers won’t come back.”

Another concern for Mr Groth is cost. How fast can the price be brought down? Personal vehicle ownership in the US is still quite cheap today. “But how can AVs promise to be even cheaper when every deployment today has to include the cost of paying an engineer or safety driver, as well as a more expensive vehicle? How fast can people pull the safety drivers to really allow this business to take hold?”

Yet if AVs do become a reality 30 years down the road, the costs of maintaining road infrastructure are likely to rise if there is a mix of manual and driverless vehicles. “Here an alternative could be to have separate driverless-only and manual-drive-only roads,” suggested Mr Groth.

Another, rather shocking speculation is that while road safety may improve, since most accidents are due to human rather than technical errors, organ donations, already insufficient, may decline – 20% of organs provided for transplants in the US come from road fatalities.

On a lighter note, Mr Groth questioned what might happen to car chases in films if AVs do roll-out. “We think Hollywood will find a solution! It usually does. But it could be boring because AVs never break rules, if they are truly cybersafe you can’t hack them… well, we’ll see!”

Cover photo: CC by Julien Chatelain