🐝 Biodiversity and transport: a crucial challenge for the future of all

🐝 Biodiversity and transport: a crucial challenge for the future of all

A session organised by Futura-Mobility on 14 March 2025 highlighted the vital importance of biodiversity to human life and how transport is impacting it. This first in a series of two meetings on the topic provided an opportunity to deepen understanding of the issues and discuss measures and solutions for a more sustainable future.

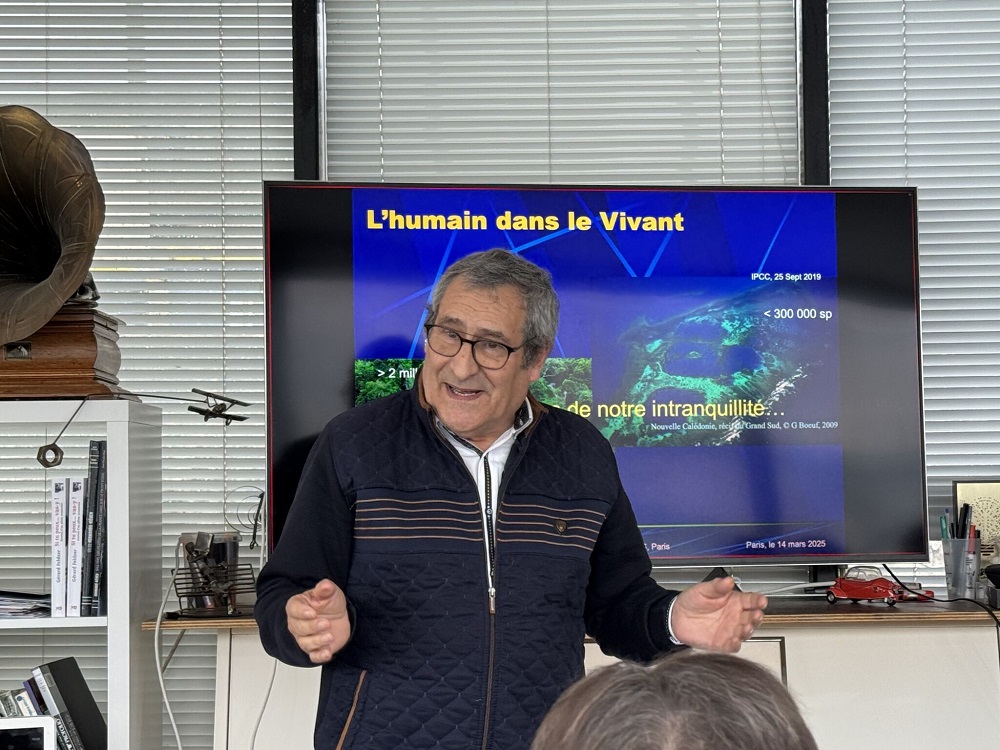

Humans integrated with the living

“Biodiversity is vital for us humans!” The gripping presentation by Gilles Boeuf, biologist, professor at Sorbonne University and former president of the French Museum of Natural History (Muséum national d’histoire naturelle), is a compelling reminder of the place of human beings in the living world and the resulting interdependence.

Biodiversity – all living things, their interactions, and the ecosystems where they evolve – feeds us, cares for us, allows us to breathe, clothe and shelter ourselves, and inspires us. It also plays a fundamental role in regulating the climate.

Among these ecosystems, the ocean, which covers three quarters of the Earth’s surface, is the primary climate regulator. It captures and stores atmospheric CO2. It stores and redistributes vast quantities of heat around the globe via ocean currents.

Water is also obviously essential to life. The human body is made up of around 65% water, and all living things need water to exist. “We have to stop devaluing water!” stresses Mr Boeuf. “The big problem is its distribution, where it falls on the planet, and how we use it.”

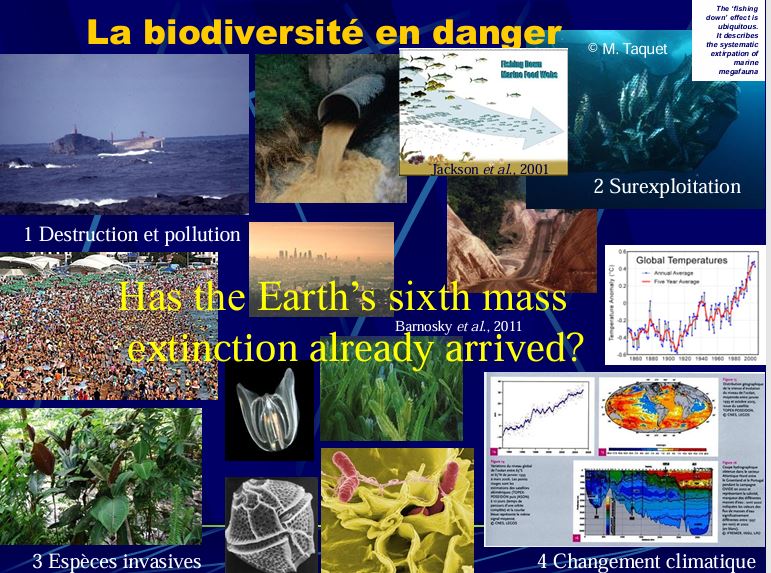

And yet human activities, with the destruction of habitats, pollution, over-exploitation of resources, the introduction of invasive species, and climate change, are weakening and even endangering the Earth system.

The growing world population and current consumption patterns are exacerbating these pressures, questioning the very sustainability of our civilisation. According to professor Boeuf, we need a “radical change in human nature,” quoting Sri Aurobindo (1915!), and must put an end to a “stupid and suicidal economy” based on destroying nature.

Mr Boeuf warns of the speed of environmental degradation. Half the world’s coral has been destroyed in just 50 years, and global warming of the oceans is accelerating: “We predicted this warming in the 1990s, but between 2022 and 2024 we had already reached the temperatures we had foreseen for 2050!”

In Europe, he deplores the near disappearance of the European sturgeon, a victim of overfishing, pollution, and dams. In the past, this freshwater fish, coveted for its ‘golden eggs’ (caviar), boasted a vast distribution area, in rivers stretching from northern Norway to Morocco, in the Baltic Sea, the Mediterranean, and the Black Sea. Now an endangered species, it can only be found in two rivers, the Garonne and the Dordogne in France.

“The worst thing we can do is nothing,” insists Mr Boeuf. Because action can indeed bear fruit, as proved by the rise in the number of fish species (including invasive!) in the river Seine in Paris. Thanks to efforts over the last few decades – stopping the dumping of untreated chemical waste, connecting large numbers of homes to the wastewater treatment system, and improving the morphology of the river with less concrete and more planted areas – backed by considerable investment, the reduction in pollution caused by human activities has resulted in species returning. However, the effects of pollutants such as endocrine disruptors need to be closely monitored.

Furthermore, living things are both useful to us and inspirational. Biomimicry – Mr Boeuf is president of the CEEBIOS centre for studies and expertise in biomimicry – can be channelled in our innovations to find sustainable solutions. Living organisms optimise energy resources, use renewable energies, recycle, function only at ambient temperature…. “The dragonfly weighs 2.5 grammes. It appeared 345 million years ago. It flies 90km on 2 Watts! Do you know anyone with a polytechnic degree who could come up with something like that?” he jokes.

Closing his presentation, Gilles Boeuf’s spoke about the One Health initiative, which highlights the closely knit links between the health of the environment, biodiversity, and human health. Emerging risks and diseases (like Covid) are mainly due to the disruption of habitats by humans.

“If we do things for living things, they work straight away. You stop fishing; you reseed; you stock and it works! If we want to encourage humans to make an effort, we have to look after living things as much as we do the climate,” he concluded.

Linear Transport Infrastructure – how to accomodate roads, rail and biodiversity

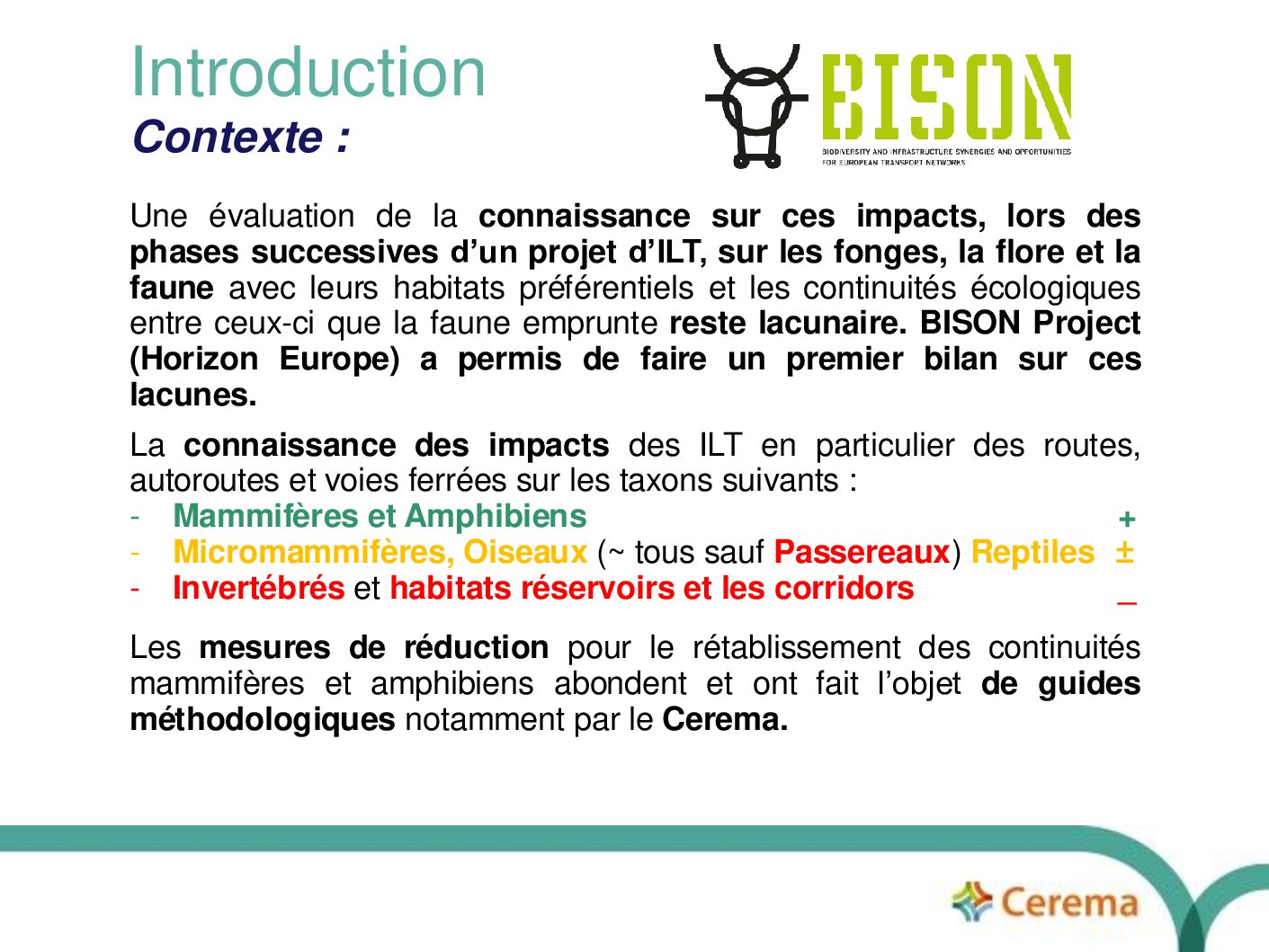

Éric Guinard, head of development and biodiversity studies, and international ecological expert at Cerema (MTES), gave a presentation on the impacts of linear transport infrastructure (railways, canals, and roads) on terrestrial biodiversity.

Since the Second World War, biodiversity has declined as the density of linear transport infrastructure has grown. This infrastructure has numerous impacts that become apparent at different stages in their service life.

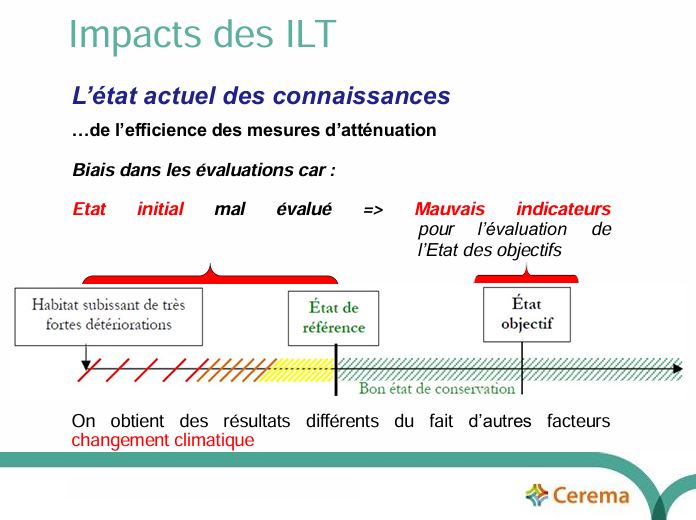

Prior to construction works, Mr Guinard believes that knowledge of the initial state of ecosystems is often insufficient. This makes it impossible to accurately assess the impacts of the infrastructure once completed and in use.

During construction, the direct impacts on the environment are significant, with the destruction of natural habitats, animal mortality, and pollution generated by the works.

Once the infrastructure is built and in operation, some land animals or birds may be repelled by light or noise, while others may find refuge in the immediate vicinity, exposing themselves to an increased risk of collision with traffic. Linear transport infrastructure has chemical impacts too, notably due to toxic substances being released into the air, water, and soil (through combustion gases emitted by exhaust pipes, tyre wear, catalytic converters, etc). As well as fragmenting habitats, infrastructure also creates the risk of collisions and facilitates the spread of invasive species.

Avoidance, reduction and compensation measures are vital, with particular priority given to avoidance in areas of significant heritage value.

With regards light pollution, Mr Guinard cites several possible actions, such as limiting road lighting in open country to dangerous junctions, switching off lighting at night, or installing low-UV emission lamps to attract fewer insects and, consequently, bats.

To curb noise pollution caused by traffic, one possible solution is restricting access to local residents only during breeding seasons in natural areas that are home to sensitive species. Other measures include using quieter vehicles or installing acoustic barriers and mounds.

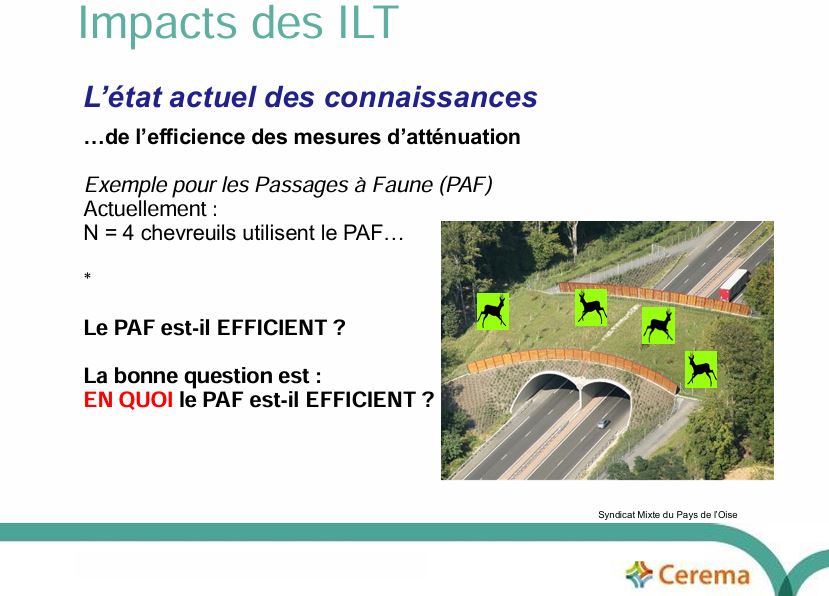

Finally, introducing wildlife crossings (together with fencing) is a vital measure for countering the barrier effect caused by habitat fragmentation.

Mr Guinard insists on the importance of measuring the efficacy of solutions adopted over the long term, beyond five years after construction. He believes the degree of effectiveness of wildlife crossings, for instance, on a species-by-species basis, could be better known. “Our knowledge of the species that use level crossings is still inadequate, due to the large number of factors that support or hinder their effectiveness, hence the need for in-depth studies based on shared and standardised protocols.”

This would require solid studies and a well-documented initial baseline, even though funding for research prior to declarations of public utility (déclaration d’utilité publique, DUP) is lacking. The effects of global warming and linear transport infrastructure on biodiversity should also be studied jointly to better assess the impacts of each factor.

He also underlines how linear transport infrastructure rarely has any beneficial impacts on biodiversity.

Éric Guinard concludes by calling for “a stronger, more inclusive vision of regional policy that takes greater account of the biodiversity issues associated with transport,” as well considering the cumulative impact of infrastructure with existing infrastructure (policy decisions to prevent major developments in quiet areas [with low road density] and concentrating ILT even more, where necessary, in areas with higher road density).

Maritime transport and cetaceans

Research by Olivier Adam, bioacoustician and professor at Sorbonne University, focuses on the impact of maritime transport on cetaceans.

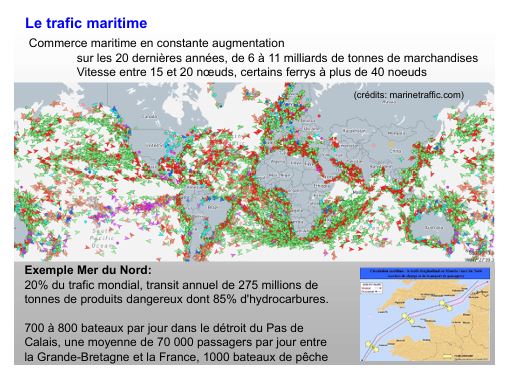

For the past 20 years – and even since the 1960s with the invention of containerisation – global maritime traffic has been steadily rising in terms of the volumes of goods transported and ship speeds. Faster ship speeds increase the risk of collisions with marine species. “It’s difficult to know exactly how many collisions occur, but they are the primary cause of fin whale mortality in the Mediterranean, and are endangering North Atlantic right whales, which are on the brink of extinction,” explains Mr Adam.

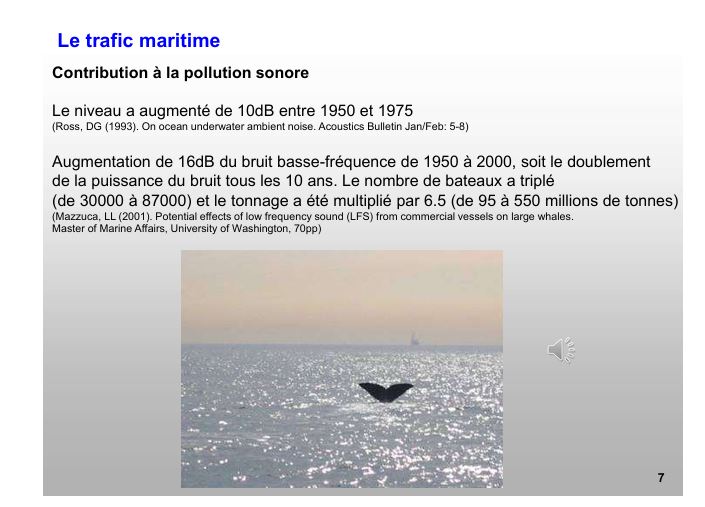

Rising noise pollution from ships is also a major issue for the maritime sector. Noise disturbs the habitats and lives of cetaceans, especially communication between individuals, feeding, diving activity, and trajectories. This nuisance may force these aquatic mammals to abandon their habitat or cause physical trauma, hearing loss, or behavioural changes.

Slowing ship speeds and banning sailing in certain areas are effective measures for reducing both the risks of collision and noise pollution. For instance, off Boston Harbour during the summer months, ships must make a diversion. Canada, the United States, and France have introduced exclusive navigation zones. Olivier Adam is nevertheless concerned these zones fail to sufficiently cover the vast expanses in the middle of oceans where cetaceans are also present.

Engineering solutions under development include installing underwater horns, called ‘pingers’, at the front of ships to warn animals, or using thermal cameras to detect their presence. Dr Adam also points out that it is technically possible to build quieter ships, citing the example of ferries, which “have done an excellent job of reducing the incessant noise on board their vessels.”

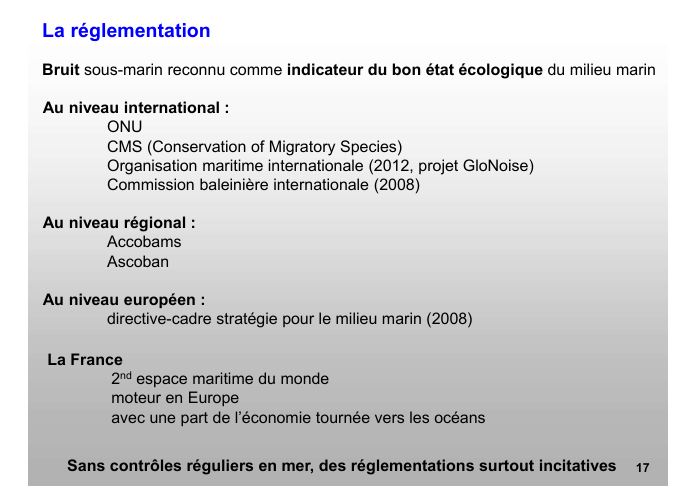

At the same time, he recognises that progress has been made on the regulatory front, with the adoption of the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (Directive 2008/56/EC or MSFD) in 2008 at European level. This directive defines a common approach and shared objectives for the protection and conservation of the marine environment. However, without effective monitoring at sea, many of these rules currently only serve as incentives.

Preserving biodiversity, a strategic challenge

This meeting strongly emphasised the importance of taking immediate action to preserve biodiversity. It also shed light on the impacts, and hence the responsibility of the mobility sector in preserving ecosystems.

“What’s the point of worrying about climate change if there’s no life on Earth?” questions Mr Boeuf. “I’m not against planes or cars, it’s the sheer number of them that’s the problem!” Mr Guimard also raises the question of transport services: which mode is best suited to which mobility need?

Preserving biodiversity is a strategic challenge for businesses and an imperative for our future. And what if it isn’t up to biodiversity to adapt, but rather for humans and society to integrate and protect it!