💡 How to better prepare for the Paris 2024 Olympic Games?

💡 How to better prepare for the Paris 2024 Olympic Games?

by Joëlle Touré, delegate general, Futura-Mobility

What lessons can be learned from the organisation of previous Olympic Games to better prepare for Paris 2024?

To find answers, the Mass Transit Academy headed by Agnès Grisoglio, also in charge of transformation at SNCF Transilien (Paris suburban rail network), has been exploring through factfinding trips to London (2012 Olympics) and Tokyo (2020 Olympics… 2021).

During the webinar organised by Futura-Mobility on 28 May 2020, members of the think tank and their guests discovered the key takeaways as presented by Ms Grisoglio.

Exceptional organisation

Firstly, some figures about organising the Games, a task that still represents quite literally an extraordinary event. “The Olympics are about 40 times the size of a football or rugby World Cup,” explains Mrs Grisoglio. “And the Games are only a success if mobility is a success,” she adds.

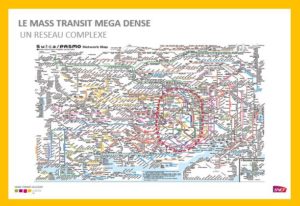

Tokyo is expecting 10% more passengers in its transport systems, even though it is one of the most populated capitals in the world with 37 million passengers a day. Sixteen metro lines carry over one million passengers!

And yet the network runs smoothly with trains crowded at peak times, filled to 200% of their capacity, separated by 2.5-minute headways. Furthermore, these fleets are operated by 42 different companies for the 60 Mass Transit lines, all without an organising authority. Considering a delay of just one minute for a train departing from an urban area can accumulate into 10 minutes on arrival, this goes to show the ultra-efficiency of the Tokyo network! Little use is made of technology, but there are some extremely precise gestures in the workplace (10 seconds to provide access for a wheelchair user) as well as simple and frugal solutions, sometimes temporary, for managing flow (duct tape to limit entry to platforms, for instance).

The way the Games are viewed differs widely from city to city. In Tokyo, the thinking is that investments must focus on everyday travel over the long term. So, when asked about preparation plans for the Olympics, the Japanese simply reply: “nothing”. Because ‘nothing’ is indeed what is being done specifically for the Games; any works carried out will be “for the good of the system”.

In London like in Paris, the extra travellers represent a massive impact because both cities are four to five times smaller than Tokyo! Hence London, as is the case for Paris, had to plan a dedicated investment programme.

In Tokyo as for all the host cities, the OGOC, the organising committee for the Games, is adapting the competition schedules to the comfort of athletes and spectators. For instance, athletics will take place when temperatures are mildest; basketball matches at times when American spectators can watch live… and never mind if they coincide with peak travel times!

In both cases, the roads are generally be dedicated to use by the Olympic teams, while mass transit remains the key tool for coping with the huge influx in people on the move.

Ways and means of managing flow

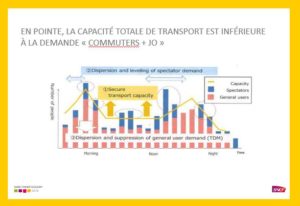

With regards passenger flow management, the idea generally accepted by all host cities is to disrupt as little as possible ‘business as usual’, i.e. everyday people mobility. “So this means ensuring the mobility of the Games is a success, i.e. athletes and spectators, as well as the mobility of the megalopolis,” says Agnès Grisoglio.

Nevertheless, nominal capacity is less than total demand during the Olympics. “Atlanta is the city that served as an example of what to avoid for London.” In the former, with its undersized mass transit network, 8% of spectators missed the 100-metre event because they couldn’t reach the stadium in time.

To ensure transport capacity meets overall demand, there are several levers available to operators:

- boosting carrying capacity and works, by adapting selected stations like in Japan, or upping network reliability (moratorium on works in London and Ile-de-France region);

- adapting signage so people unfamiliar with a network can use it easily, which in turn improves overall passenger flow. In this sense, Japan also faces the challenge, led by government, of opening up Japanese society to others – be they foreigners or people with disabilities;

- organising visitor flow by pointing out preferential routes or even programming events after competitions to stagger the departure of spectators from the Olympic site;

- juggling the transport demand of the local population. Since the Covid-19 crisis, going forward it may well prove easier to encourage people to work from home, to change their travel times or use other transport modes, or to avoid certain stations or lines. “London did this and thanks to travel demand management they reduced demand by 30% and the Games were a success,” explains Ms Grisoglio. Each country communicates in its own way about this lever for managing demand – fun in London, more direct in Tokyo:

These lessons learned are not only valuable for organising Olympic Games but also for mass transit flow in general. “We have added travel demand management to our wheel of excellence for mass transit management, just as Transport For London did to cope with flow during major works on its lines,” concluded Agnès Grisoglio.

Cover photo: Кирилл Соболев – Pixabay