💡 Transport Demand Management

💡 Transport Demand Management

by Joëlle Touré, delegate general, Futura-Mobility

31 May 2022: Futura-Mobility organised a conference with speakers from five different countries on the theme of Transport Demand Management. The session, in English, explored the issue of top-down management of transport flow in urban areas.

This is not about Mobility as a Service (MaaS) – providing travellers with different journey route options – but a question of directing flow in cities for better circulation of traffic, to reduce CO2 emissions by promoting less carbon-intensive modes of transport, curb pollution, and make everyone’s journey more of a pleasure. So the idea is about influencing behaviour without hindering freedom of movement.

The subject concerns passenger transport as well as transporting goods and parcels in cities. It affects all transport modes on the roads, rail and river, and covers both individual and collective modes of travel.

Obtaining sustainable results

“Transport Demand Management is quite discreet, but can be quite effective,” says Emmanuel Dommergues, head of the Governance Unit and manager of Transport Authorities & Informal Transport Committees, UITP (International Association of Public Transport).

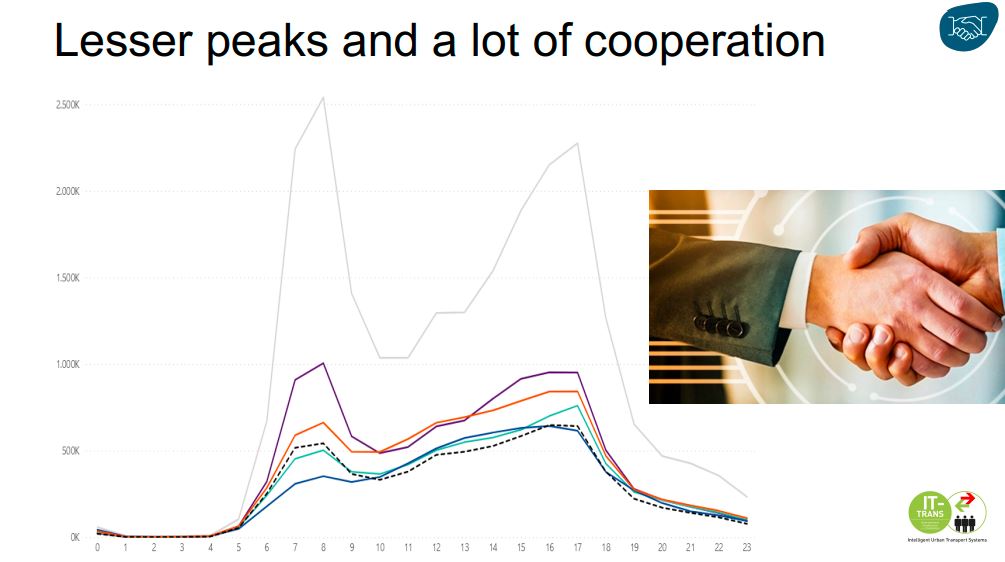

In the Netherlands, for instance, the hyper-peak in public transport – the busiest 15 to 30 minutes – has been smoothed out by changing school and university timetables. “Students represent over 50% of passengers in the Netherlands,” explains Chris Beghin, strategic advisor at Keolis BENELUX, adding: “The hyper-peak is an invisible financial disaster! […]. It also creates disruptions: when a system reaches maximum capacity, it becomes unstable as well as uncomfortable for passengers.”

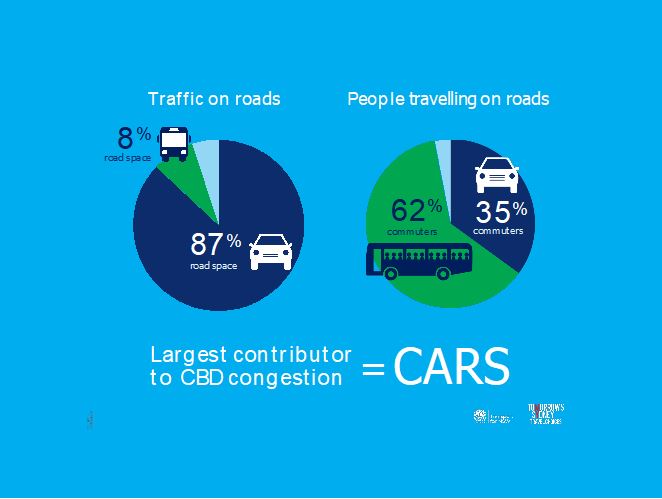

Another example from across the globe, in the city of Sydney. Rose McArthur, director of Transport and Highways, Cheshire West and Chester Council, and previously a specialist consultant, worked on decongesting the only north-south traffic route into Sydney’s city centre, which is heavily used by people travelling to and from work. The city was about to embark on a three-year project to build a new light rail line on George Street, a move that would reduce this street capacity by 38%. The first finding was that 87% of the space was occupied by private cars and only 35% by commuters.

By working closely with employers and bringing 564 businesses on board the project, “the number of vehicles entering Sydney’s city centre was reduced by 11% during the morning rush hour, and public transport saw a 9% increase in ridership,” says Ms McArthur, delighted.

“It takes a lot of energy to get results, but when you do, they are real and lasting,” she confirms.

New skills for changing behaviour

Implementing such studies, incentives and measures calls for integrating multiple disciplines.

“Travel Demand Management is now a really well established and integrated discipline,” expands Ms McArthur. “It focuses on behaviour change, the part that is often overlooked, as well as technology solutions and creating new capabilities. It requires a wide range of skills and inputs.”

Indeed, for Emmanuel Dommergues, “Demand Management doesn’t just concern data management, technology, and mobility. It really taps into psychology and sociology.” These areas of expertise are seldomly applied in the traditional transport world, which remains a sector where engineers from the so-called ‘hard’ sciences work.

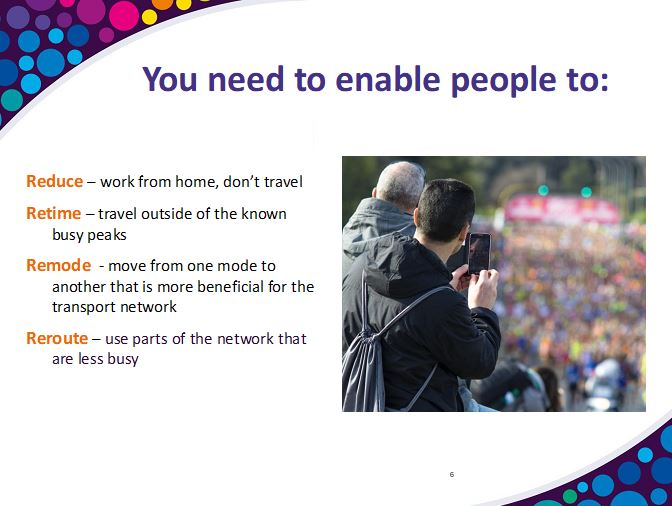

For Ms McArthur, the aim is to change behaviour from four angles, “the 4 ‘R’s’: Re-route (change route), Re-mode (change mode of transport), Re-time (change travel times), Re-duce (reduce travel).”

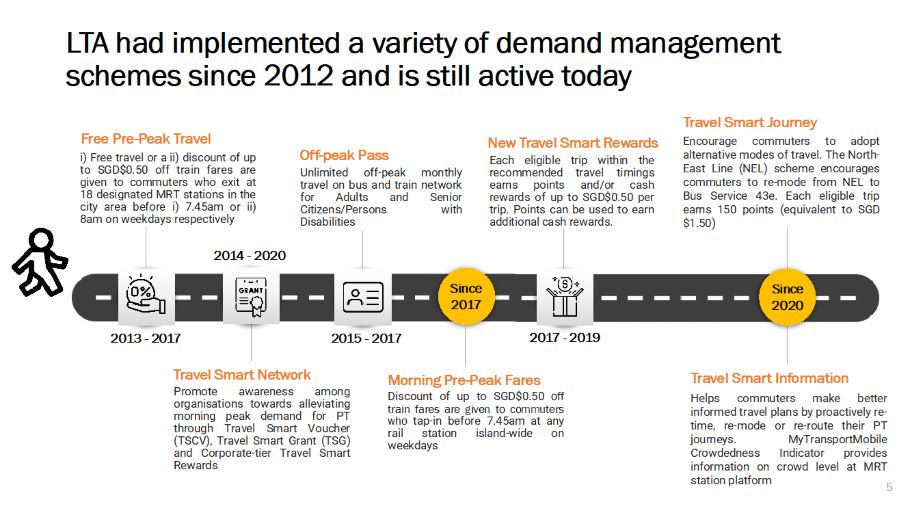

In Singapore, Priscilla Chan, deputy group director in charge of public transport, Land Transport Authority (LTA), highlights the city-state’s approach to the issue of mobility behaviour: “nudging is also part of Travel Demand Management.”

Since 2012, many trials have been carried out in Singapore. This include encouraging passengers to take another, less crowded, mode of transport or change the time they travel to work to distribute the load.

What really stands out in Singapore is detailed approach. It precisely targets certain time periods, selected rail lines that are the busiest, or a specific segments of population (senior citizens, working adults, etc.), to encourage people to adjust when their travel patterns. LTA makes use of several incentives – lower fares, free travel, money rewards, and information to change mobility behaviour. For the roads, a quota for the number of cars on the road coupled with a precise, real-time urban toll system enables smoother traffic flow.

One piece of advice from Priscilla Chan on Travel Demand Management, after years of experimenting in Singapore: “don’t be afraid to try and test out different measures.”

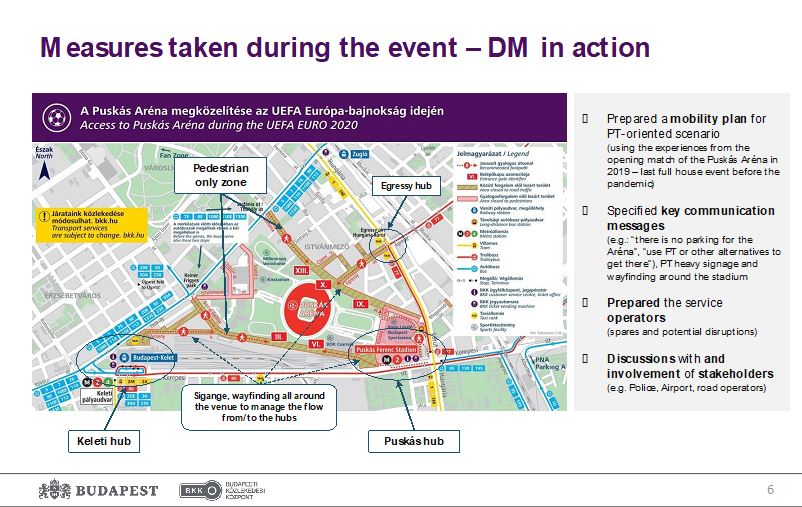

In Budapest, in the run-up to Euro 2020, the plan, according to Máté Kádasi, transport organisation associate, BKK Centre of Budapest Transport, was to “create an environment that encourages distribution of demand – using nudging – with appropriate incentives and disincentives.” Disincentives like, for instance, closing streets to car traffic or introducing parking restrictions around the stadium. The main incentive was introducing strong communication explaining how spectators could reach the stadium using soft mobility, with public transport and walking in mind.

For the 2012 London Olympics and in Glasgow for the 2014 Commonwealth Games, humour was often harnessed to better get the messages across.

Rose McArthur is keen to point out “the complexity behind this simple message, because of the sheer number of agencies involved [City of London, National Rail, Department for Transport, Highways, Transport for London…] and amount of data we had to integrate.”

Understanding what already exists is crucial

For this, “data is where everything starts. In Travel Demand Management, you can only move forward when you know what you need to rebalance. Then you have to understand your population, segmented by mode, geography, travel purposes; then obtain this information before, during, and after their trip; and finally use the right communication channels for driving change among these travellers.”

So for Transport Demand Management, you must fully understand the transport flow before starting to think about any particular issues in a city.

In Panama City, for instance, by implementing a system compiling existing data, with Alstom’s Mastria as integrator, some concrete benefits could be demonstrated for the Metro Services. Using existing data flows and implementing a real-time Artificial Intelligence Prediction algorithm, passenger travel time has been reduced by 8% and passenger distribution in cars by 6%. The frequency of trains, or direction of escalators, or number of turnstiles in stations can be adapted dynamically according to demand fluctuation. “We try to use all the existing data streams instead of introducing IoT or devices that consume a lot of bandwidth,” explains David Moszkowicz, director of Alstom‘s Smart Mobility Center. “We already have lots of data from many sources for public transport – for example, from advanced software like ticketing or Mobility as a Service applications.”

Henceforth, the challenge is to extend data collection to all modes of transport. In Panama City, the next step is to integrate data from the bus network, road traffic, parking, etc. Meeting this challenge means breaking down the silos of transport modes, which isn’t always easy! “It makes implementation difficult because everything – the different transport systems – works separately in terms of governance,” adds Mr Moszkowicz.

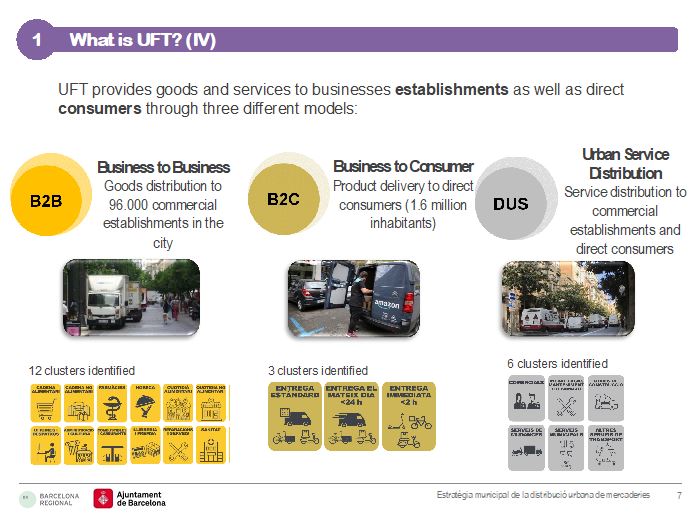

In Barcelona, Manuel Valdés López, manager of Mobility and Infrastructures at Barcelona City Council, is working on an ambitious plan for urban goods transport. “We have found there is an overall lack of understanding of the activities of this supply chain, of all the other activities of urban life, and how they can coexist,” he points out.

Another problem identified in Barcelona is that urban freight transport is a highly fragmented sector, with a great many private stakeholders that seldom communicate among themselves.

Breaking down silos between transport modes to gain an overview

Many stakeholders are involved in these projects. In London and Budapest, for the 2012 Olympic Games and Euro 2020 (postponed to 2021) respectively, the various city departments, the event organiser, public transport operators, the police, airports, road managers, and so forth, all had to be on board.

In Sydney when decongesting George Street, or in Barcelona for boosting logistics flow in the city, private businesses have been linked into these actions.

In the Netherlands, government itself was involved since it made it compulsory, by law during the Covid crisis, for schools and universities to play a part in reducing the transport hyper-peak. Working at all levels was a must: at national level with the Ministry of Education, at regional with public transport operators, at local with school groups and universities. According to Chris Beghin of Keolis Benelux, it is important to “first build personal relationships with schools and universities at all levels and explain how it [the approach] benefits them, before asking them to change and play an active role.”

This leads Mr Dommergues of UITP to point out how “Demand Management is mainly in the hands of stakeholders not coming from the transport sector. So this means transport stakeholders are going to have to leave their comfort zone and act as a driving force to ensure the non-transport specialists are closely involved in this action.”

Working on the existing network and new infrastructure in parallel

Behaviour change initiatives work in addition to efficient management of the existing network and the expansion of transport services. Of course, these actions are integrated to a given territory and culture. “So it won’t be the same in Singapore, Budapest, or a rural area,” points out Emmanuel Dommergues.

In this regard, Rose McArthur refers to the work of Professor Glenn Lyons on ‘triple access planning‘ – ensuring people have access to essential services close to home, or access to transport links, or access to good digital connectivity. “So essentially this triple access planning is about managing movement in cities.”

In Barcelona, the urban logistics plan mainly focuses on boosting the offer in terms of infrastructure or better sharing uses of existing infrastructure. This represents a massive challenge given that “growth in e-commerce will increase the demand for urban logistics by at least a factor of two over the next three years,” analyses Bruno Gutierres, Director of Mobility Orchestration and Collaborative Innovation at Alstom.

In Barcelona, €250,000 is being spent on urban distribution initiatives within the city. The most important short-term initiative aims to set up urban distribution hubs for transporters. Goods arrive at these hubs massified and leave in parcels transported by deliverers for the last mile.

On the subject of shared use, the city is introducing flexibility to how public space is used, for instance, by encouraging overnight deliveries to 50 – and soon 200 – of the city’s markets. The objectives here also include working on reducing the noise pollution generated by this traffic and playing on tiered use of parking spaces, depending on the time of day.

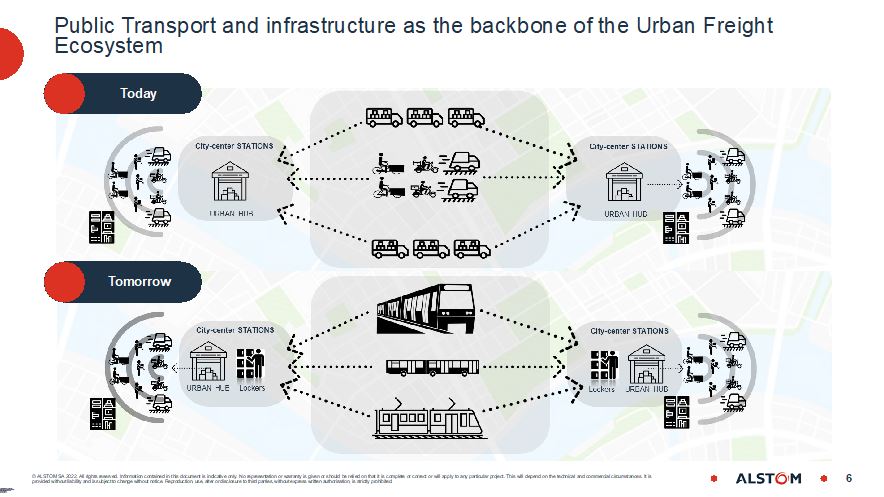

The city council is exploring the possiblity of using the metro to transport goods and packages. Manuel Valdés López explains how “this idea closely ties in with our plan. We’re trying to use the metro or train stations located in the city to introduce different ways of transporting goods.”

This is not a new idea. Alstom, who is interested in this solution, did a study to find out why, up until now, it has failed to take off. “The results point to issues over loading parcels, managing passengers and flow, and a lack of collaboration with logistics people,” explains Mr Gutierres.

Yet according to Bruno Gutierres, using available capacity in public transport for the needs of logisticians could represent an addition source of revenue for transport operators. “Using Mastria, we could predict available capacity,” he explains, “and link up public transport operating systems with logisticians’ tracking systems in a kind of marketplace.”

For public transport operators, this is a real change to the way theiy view their job, even their business model. “The right model has yet to be found,” analyses Manuel Valdés López. “Carrying goods isn’t part of the remit of public transport operators, so why should they do it now?”

Transport Demand Management, a must

So Transport Demand Management aims to optimise the use of existing infrastructure and could help meet the challenges of mobility in the city (congestion, emissions, pollution, etc). For Rose McArthur, “from the city perspective, constantly building new infrastructure isn’t going to help. More car parks and roads aren’t going to deliver the mobility and change you need. I also think the technology fix will only go so far.” Thus she believes over 40% of efforts to curb climate change must come from behaviour change.

This discipline calls for new skills, an approach based on experimentation and tenacity, and often leads to the stakeholders involved changing the way they view their roles. For instance, “in the U.K., road manager National Highways has made Travel Demand Management compulsory when roadworks are planned,” explains Rose McArthur. “So any road closures are now accompanied by a solid strategy in terms of Travel Demand Management.”

For Emmanuel Dommergues from UITP, “it’s time to see Demand Management as an everyday transport planning tool.”